Authors: Sergei Kostin

Farewell (15 page)

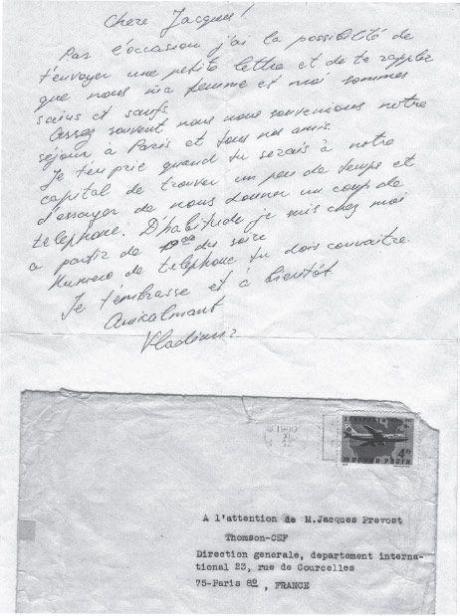

Figure 2. First letter to Prévost, mailed in Hungary.

Vladimir asked his brother-in-law to mail an innocuous postcard, supposedly addressed to a French friend, while in Hungary. It was simply to arrange a rendezvous, implying that Prévost was supposed to come to Moscow to meet Vetrov. The wording of the message was very cautious. Vetrov had to be able to explain himself should the letter be intercepted by the KGB. Barashkov, like most Soviet citizens, viewed the security measures imposed by the KGB as some kind of a paranoia, and censorship as a disgrace. He was thus glad to render this service (

see Figure 2

).

The DST did not make a move.

8

Actually, Prévost would not have taken a big risk had he traveled to Moscow and called Vetrov the way he used to do it in the past. The DST’s lack of response to this first contact attempt from Vetrov, in a situation where it had nothing to lose and everything to gain, was due only to a procedure. Accustomed to double-dealings, the French service saw traps everywhere. On the other hand, being a counterintelligence service, the DST would have had, in theory, an interest in having a mole within the KGB only if that mole could give them information on the activities of the KGB Paris residency. It had not occurred to the DST yet that they might play a role in gathering intelligence outside of France, which in both cases would have been beyond the legal scope of its responsibilities. The DST was in the situation of a hunter who spends his time shooting sparrows in his field and is suddenly offered a safari. This is probably what Vetrov thought.

Two months went by—enough time to conclude that the first attempt to renew the contact had failed. Maybe the letter never reached the addressee, or perhaps the contents were too unspecific for Prévost to understand the urgency of a prompt answer. However that may be, Vetrov decided to try again.

In February 1981, a trade show had been organized in the Moscow International Trade Center, also known as the Armand Hammer Center, named after an American businessman who actively promoted East-West trade relations. In spite of the interdiction against communicating with foreigners, Vetrov was not taking a huge risk by visiting the exhibits. There is always some margin between rules and their enforcement, and in the USSR the margin was significant. It was a trade show in electronics. There were French companies among the exhibitors, and Vetrov was a specialist in both electronics and French business. He could always argue that this visit was in the context of his professional activities, to see what improvements had been made in devices he had provided to the KGB in the past, and so forth.

9

Once at the trade show, Vetrov soon located just the right man among the French exhibitors. It was Alexandre de Paul, a Schlumberger representative who had come from Paris for the occasion. We were not able to establish whether Vetrov already knew him from the years he spent in France, and whether he knew that Alexandre de Paul was an “honorable correspondent” of the DST as well. These are two likely possibilities since Vetrov gave Alexandre de Paul another message for Jacques Prévost. This second message was much more explicit. It contained the following words: “You must understand that this is for me a matter of life or death.”

10

In fact, this second message was received by the DST at the same time as the first one.

11

Raymond Nart had been promoted since Vetrov had left France. He was the head of the DST USSR section. However, he did not handle Prévost directly anymore, which caused a delay in the transmission of the first message. Nevertheless, the Vetrov file was pulled out again, and “R23” sensed immediately that the messages were an offer to collaborate.

12

The possibility of a setup by the KGB was of course a consideration. Hence the importance of sending the right individual on reconnaissance.

This was logically a mission for Prévost. First, he knew Vetrov personally, so nobody else could assume his name to meet with Vladimir. Secondly, since Prévost was intimately acquainted with him, he should have had a better sense of a potential provocation. Last, being a DST honorable correspondent, he would know better how to react in case anything unexpected cropped up.

Consequently, Nart asked Prévost when he was planning to go to Moscow next. A KGB machination remaining a possibility, Jacques Prévost was understandably not keen on carrying out this mission in Russia himself. It was one thing to travel back and forth between Paris and Moscow on business; it was another to respond to an SOS message from a KGB officer! Besides, Prévost’s responsibilities had changed as well since the seventies, and he was not going to Moscow nearly as often as he used to. It was, therefore, in good conscience that Prévost told the DST that, although he still had some business in the Soviet Union and at some point would have to go back, he had no trip scheduled in the immediate future.

The tone of urgency in the message, and the fact that his service had been “a bit slow on the uptake” at the reception of the message, made Raymond Nart pursue his efforts to rapidly find another correspondent to answer Vetrov’s call.

Why not send Alexandre de Paul? He too knew Vetrov and was not an outsider. Schlumberger even had an office at the chamber of commerce in Moscow, so if he were to go back there, that would not arouse suspicion. Alexandre de Paul, however, presented the same disadvantage as Prévost, since he might have been identified as an honorable correspondent. He was thus ruled out as a candidate for the job, and his name would never come up again in this story.

In the end, the DST decided to transmit the answer to Vetrov’s message through somebody uncompromised, entirely innocent in the eyes of the KGB. Prévost is the one who suggested the name of the Thomson-CSF general delegate in Moscow. Furthermore, this individual was scheduled to go back to Moscow a few days later.

That morning of late February 1981, the man considered for the task did not suspect anything when he stepped into the office of his boss and friend Jacques Prévost. To understand the development of the story, it is important to get acquainted with this key character.

The Adventurous Knight

Born on January 7, 1923, in Paris, Xavier Ameil transcends class and social status categorization. He is a remote descendant of colonel Ameil, who served in the twenty-fourth regiment of cavalry (Regiment de Chasseursa-Cheval) and was made a general and a baron of the Empire by Napoleon after the battle of Wagram. But Xavier Ameil went through his active life without flaunting his peerage, only using his title of baron when retiring in Touraine, a place where belonging to nobility has its importance. Xavier Ameil’s father had studied at HEC (Ecole des Hautes Etudes Commerciales) and worked as a salesman for a large hardware company, Japy, in the Paris area. He died young, when Xavier was only twelve years old. His mother was the granddaughter, daughter, and sister of graduates from Polytechnique, one of the most prestigious French engineering schools. A widow with six children, she taught them to fend for themselves.

Xavier grew up in Paris. After graduating from high school, he was also admitted to Polytechnique. After two years, he interrupted his studies. It was 1944, and France was being liberated from German occupation. Xavier joined the Leclerc Division and was in Strasbourg when the war ended. A local enterprise, the Société Alsacienne de Constructions Mécaniques (SACM), funded him for two years to study at Ecole des Télécommunications. The company did even more for Xavier; the Alsacienne is the place where he met an adorable executive secretary who became his wife.

Claude Goupil de Bouillé was the daughter of a squire living in Bourgueil. She was educated in a Catholic school, graduated from high school, and then studied law and secretarial work in college. She married Xavier in 1951 and quit her job, becoming a housewife with two children, a boy and a girl.

In 1953, Xavier Ameil was hired by CSF (Compagnie Générale de Télégraphie Sans Fil), where he became deputy director of the research lab. His greatest success happened in the years 1963–1965, when he put together an excellent team of engineers and manufacturers who created a technological wonder, the Myosotis teleprinters. Those encrypting machines would eventually equip all the French embassies worldwide. This was a huge market for CSF, amounting to over a billion francs. The French government viewed those machines as a valuable achievement and therefore made Xavier Ameil Knight of the Legion of Honor.

The design of these teleprinters was so innovative that a special version was developed to be integrated in the RITA system (military telecommunication integrated network) in 1982–1983. It was an emitter-receiver allowing the transmission of voice commands in an encrypted form. It was considered as a high-performance system, and the U.S. Army bought it.

In 1978, in order to manage a big contract involving the modernization of Soviet television for the Moscow Olympics, Thomson-CSF put in place a significant office in the facility of the Soviet-French Chamber of Commerce, located at 4/17 Pokrovsky Boulevard in Moscow. The company already had a representative there, but for this important contract, a new team was needed, headed by an experienced and competent general delegate, so they offered the position to Ameil. Ameil had stayed in the Soviet Union twice before, two weeks in June 1969, and five weeks in November and December of 1978. He liked the country and was not afraid of taking on responsibilities, so he accepted the offer and moved to Moscow with his wife on January 5, 1979.

The Ameils moved into the basic three-room apartment occupied by their predecessors, on Vavilov Street. Claude was fairly unhappy to have to live in a mere housing complex. Finding another apartment was not so simple, and Xavier was totally absorbed by his work. Further, the budget he had available was for the office, which he equipped increasingly better over time.

The couple did not have much of a social life. Xavier had quite a few British acquaintances, but Claude did not speak English. Every once in a while, the Ameils would invite French people over, especially after Claude started working as a volunteer at the embassy library. They both appreciated Russian culture and never missed a performance at the Bolshoi Theater. They knew very few Soviet citizens, the political climate being unfavorable to relations with foreigners. Being overly cautious, they would see a French-speaking Russian friend with the utmost prudence.

Xavier Ameil, Vetrov’s first handler (this photograph is the one used on his visas, kept in the KGB archives).

Xavier traveled to Paris often to discuss ongoing business issues. According to his KGB file, he went back and forth seven times in 1979 and six times in 1980. After the Olympics television contract, Thomson-CSF landed two more large contracts, one for the building of a telecommunication system (PBX) manufacturing plant in the Ural, and the other for the installation of a monitoring system and computerized remote control for gas transportation. For this reason, in late February, not even two weeks after his previous trip, Ameil went back once more to the Thomson headquarters.

In a previous chapter, we discussed the exchange of services between Thomson-CSF and the DST, and the role played by Jacques Prévost. Prévost always denied any involvement with the DST to his subordinate and friend. Xavier Ameil, who was not that naïve, was therefore not surprised when his boss introduced him to a DST representative waiting in the office. The man who stood up to shake hands with him was a certain Rouault. Ameil would later learn with amazement that Rouault’s nickname was “the killer.” He was a handsome man with dark hair and fine features, with the look of a Spanish grandee. Reality was less glamorous: Rouault was Raymond Nart’s assistant.

Prévost explained the affair to Ameil, telling him only what was absolutely necessary. He said that one of his Soviet contacts, Volodia,

1

a KGB member, had sent him an SOS claiming a matter of life or death. Prévost asked if Xavier would call Volodia in Moscow to transmit a verbal message.

Ameil answered yes immediately. When asked, fourteen years later, why he accepted so fast, he recognized that he never had a second thought about it. He explained very simply, with an ingenuous smile, almost embarrassed, “Because I wanted to be helpful.” As he was saying those words, he did not have in mind his boss Prévost, nor the DST, nor his country. He only thought about a man finding himself in difficulty, a friend of Jacques’, a human being in trouble in the Soviet Union, a situation that could happen to so many people.

With respect to the choice of the messenger, Ameil had given some thought to that question. In his opinion, the DST had a blind belief that it was a call for help, but did not suspect for a minute that something “big” could come out of it. So they preferred to send a lamb rather than a wolf to check out the situation on the ground.

As it turned out, the DST was certainly right to act that way. “An amateur has the disadvantage of not being trained for the job, but the advantage of not being suspected by counterintelligence services,” explains expert Igor Prelin. “All things considered, it was a net advantage here. Ameil was never monitored nor even suspected of anything.”

2

In contrast, we know today that Jacques Prévost had indeed been identified by the KGB as an agent of French counterintelligence as early as 1974. Ameil’s watch file was blank. As far as routine civilian surveillance was concerned, his “guardian angel” at the UPDK sent very flattering reports about him; the Thomson representative used to tell the UPDK staff about the slightest difficulties he was encountering in everyday life. Soviet counterintelligence informants described him as an innocent daydreamer, a nice fellow, well-read and courteous.

Incidentally, the KGB did not change its mind about Ameil, even after his role in this espionage case had been clearly established. Ameil had not been playing the part of an agent with its inherent deception, always being himself, which earned him the respect of the KGB.

By chance, in early 1980, Sergei Kostin met the couple in Moscow. Claude Ameil and Kostin happened to take part in the shooting of a comedy called

One Day, Twenty Years Later

. Claude was playing a Frenchwoman, a member of a delegation visiting a large Soviet family; Sergei played the interpreter of the delegation. The script called for him to drive the Ameils’ car, a white Renault 20, the very car used in the beginning of this incredible espionage adventure.

Fourteen years later, in September 1994, Kostin called the Ameils while he was in Paris. He had with him the videotape of the film the couple had never seen. In spite of all those years with no contact between them, Claude was delighted to hear from him, inviting Kostin to come spend the weekend with them in Touraine. He thus had the opportunity to stay in the lovely property where the couple spent most of the year, a former priory in the middle of the woods.

Kostin had no indication that Xavier would agree to reminisce about his adventure. However, the couple was glad to oblige their guest. They spent a morning and most of the afternoon talking into a recorder microphone, recollecting the various episodes of their Moscow years. Xavier did the talking first, while Claude was attending Mass. Then it was Claude’s turn to tell her story while Xavier went to church.

Their testimony as a whole exuded authenticity. Xavier is a phenomenally cultured man, knowing technical subjects, but also having an interest in history, economics, arboriculture, and no doubt in many other fields they did not have the time to talk about. From his point of view, the Farewell case was definitely an exciting adventure, but without significant impact on his life. Similarly, Claude’s remarks revealed the same integrity as her husband’s, with a lot of common sense and a strong sense of humor.

The Ameils never tried to be dominant central characters. When memory failed, they did not make something up. If they thought they should not answer certain questions, such as how to contact the Ferrants, the couple who took over the handling of Vetrov in Moscow, they would say so. There is no evidence that they hid anything. The part they played in this story was such that they certainly had nothing to hide. They gave an account of those events from the perspective of people who considered it their duty to do what they did, who had nothing to reproach themselves with, and nothing to gain from their participation. The authors consider this side of the story as truthful and complete, short of involuntary omissions made by them.

3

Having accepted the DST mission, Xavier Ameil went back to Moscow on March 4, 1981. He did not want to call Vetrov from his apartment, believing their home phone was tapped. So he promptly called Vetrov’s home from a phone booth.

He first got Svetlana, who told him to call back in the evening, which he did.

This time, Vladimir answered the phone.

“Hello!”

“

Bonjour! C’est Volodia?

” asked Ameil.

“Yes.”

“I am a friend of Jacques Prévost. I have a message for you.”

Vetrov understood right away. He told Ameil to meet him the next day in front of the Beriozka, a store open only to foreigners, located on Bolshaya Dorogomilovskaya Street.

4

Ameil knew the place and agreed.

It was in front of this grocery store for foreigners that Vetrov initially met with his first French handler. The apartment building where Vetrov lived is visible in the background.

He went to this rendezvous without the slightest anxiety. He was convinced he would meet with a poor fellow in difficulty, and that he would help him out by transmitting the message from the DST. His role would stop there.

Ameil parked his Renault in front of the store. Vetrov walked to the rendezvous. Both men shook hands and got in Ameil’s car. Remember, March in Moscow is still the middle of winter.

To prove he truly came on Jacques Prévost’s behalf, Ameil showed Vetrov his boss’s business card. Then he delivered the message:

“Jacques asked me to tell you that the borders of all the European Community countries are open to you. France is ready to welcome you if you can get out of the USSR.”