Farewell (17 page)

Authors: Sergei Kostin

What is even more astonishing, when boarding the plane to Paris in early May, Ameil still had the briefcase under his arm. As he stood in front of the Soviet customs officer checking his things through the X-ray machine, he was congratulating himself for not having placed the documents in his suitcase. He preferred to focus his thoughts on that point rather than trying to anticipate what he would do if asked to open the briefcase. “Reckless” maybe, but he was very aware of the risk he took.

On May 11, the day after the presidential elections and François Mitterrand’s victory, Ameil went to his second meeting with the DST executives. This time, Rouault (“the killer”) was with his boss, Raymond Nart. The two spy hunters listened very carefully to Xavier’s account of the various episodes of his “Robinsonade.” Unlike Ameil, they already knew the exceptional value of the documents he had sent them. The tone of the conversation was very businesslike. There was no congratulation or praise, only a discussion about the measures to be taken in the future.

They had already thought about what to do with their innocent lamb who had changed into a fox. It was now clear that the task was too dangerous even for a gifted amateur! Nart announced to Ameil that a professional would take over from him. He could not give his name. He vaguely described him as a military man posted at the French embassy, a man he knew well and trusted completely, who had been in Moscow for a while.

“You’re talking about Ferrant?” asked Ameil spontaneously.

Nart was stunned.

“You know him?”

“Yes, very well.”

The French embassy staff was not that big. Claude was the one who had contacts there. She worked at the library, and Madeleine, Patrick Ferrant’s wife, was among the regulars. Both women hit it off. After that, the two couples invited one another over for dinner several times.

So Nart asked Ameil for a last service. The Thomson representative had no objection to introducing Ferrant to Volodia when he returned to Moscow.

Ameil was thus replaced, but in the event of the operation failing, his safety could be in jeopardy. Nart offered to give diplomatic passports to Xavier and Claude. This way, in a worst-case scenario, they could only be faced with expulsion from the Soviet Union. After giving it some thought, Ameil turned down the offer. It might attract attention to them, and from them the KGB could trace back to Volodia. Then, bad debts making bad friends, Nart insisted on reimbursing Ameil for the expenses he had in Moscow for Vetrov’s benefit.

Nart gave his word to Xavier, who was grateful for it, not to exploit the information provided by Vetrov before the Ameils returned to Paris for good. In any case, for the operation to continue, they could not act otherwise. A few measures were taken immediately. For instance, Bourdiol was transferred to another job that he could view as a promotion, although it did not give him the same access to confidential information. The main point, assured Nart, was that there would be no arrests and no expulsions of KGB members, nothing that could arouse suspicion within Soviet counterintelligence.

Ameil was relieved to put an end to this episode of his life. Not only because of the risks he was taking, but also because he was bothered about having drawn his company into this espionage story. Jacques Prévost had even informed the CEO of Thomson-CSF, Jean-Pierre Bouyssonie, of the situation, with the vague declaration, “With the DST, we got involved reluctantly in an affair of paramount importance for the security of France and the West as a whole. Can we continue?” A good patriot, the head of Thomson-CSF gave his consent.

Considering his activities, Ameil was also uneasy with his Soviet staff and his Soviet business partners. While he knew that some of them were obliged to report him to the KGB, he was annoyed with himself for having betrayed their trust by helping his own country’s secret service. Whichever way we look at it, and in spite of the tremendous advantage France gained from the Farewell dossier, the consensus is that the reputation of Thomson-CSF in the Soviet Union was damaged by this affair.

During his trips to Paris, Ameil had a few more contacts with DST officials in charge of the dossier. The purpose of those meetings was either to provide more precise information regarding a point or another in his reports, or to clarify an aspect of Volodia’s personality. He thus met again with Nart, who managed the operation, with his deputy Rouault, and later with Yves Bonnet, nominated as the head of the DST in December 1982. Ameil was never granted the honor of meeting with Marcel Chalet, who had been overseeing the operation.

As for Volodia, Ameil saw him once more, on May 15, 1981, to brief him about the first contact with Patrick Ferrant, his successor. During their previous rendezvous, at the end of April, Xavier had mentioned that another person would take over, more qualified for this type of operation. Vetrov had understood perfectly, and feeling the operation was about to become more professional, he had used the opportunity to draw up the ideal profile of the person to send for the initial contact. “It should be a woman, if at all possible. The best would be to meet her at the Cheryomushki market, on Fridays. It is a very busy place, but I’ll recognize her without difficulty.”

Vetrov knew that, in spite of its large staff, Soviet counterintelligence did not have the material means to tail women, not even the wives of known intelligence officers. He knew the place, which was one of the best-stocked kolkhoz markets of the capital; he went there from time to time to buy fresh produce.

After a final warm handshake, Ameil said goodbye to Volodia and, for the last time, transmitted Farewell’s latest wish list to the DST.

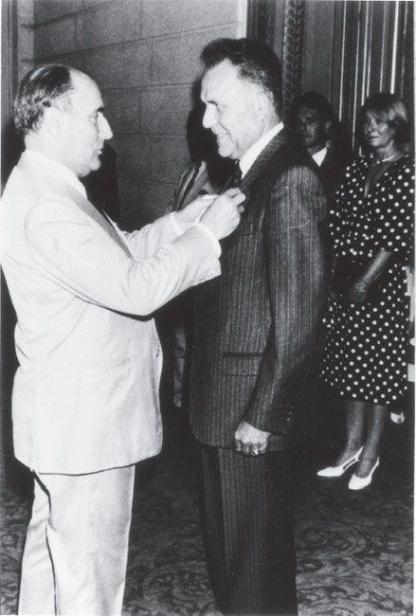

President Mitterrand pins the rosette of Officer of the French Legion of Honor to Xavier Ameil’s lapel. To protect secrecy, Farewell’s first handler was awarded this decoration for services to foreign trade, but Mitterrand whispered in Ameil’s ear, “I know what you did for France.”

An Easter Basket for the DST

Let us try now to look at the operation from Vetrov’s and the DST’s perspectives. What could have been Vetrov’s thoughts regarding the DST’s attitude toward him? Viewed from Moscow, it probably looked like the motion of a pendulum.

When Vetrov was posted to France, the DST through Jacques Prévost surrounded him with attention and, on the eve of his return to Moscow, suggested he could ask for political asylum. Even after his refusal to defect, the DST maintained the contact with him through Prévost. So, from 1965 to about 1973, the Soviet officer was undeniably in favor with French counterintelligence. Then, after Prévost’s last trip to Moscow, the DST seemed to have written him off. It even denied him an entry visa to France, which would have provided a good opportunity to pursue its study of the target for several years longer (as was mentioned earlier, Vetrov had no way to know the visa was denied because of an administrative blunder). At that time Volodia did not present any interest anymore. However, with the pendulum motion going the other way, the DST did not prevent its Canadian allies from opening their borders for him. It eventually forgot him for good, since Prévost never called his friend again in spite of dozens of trips he made to Moscow in those years.

And here was Vetrov sending his SOS out of the blue. The DST realized that its former study target could become a fruitful source of information on Soviet espionage in France. And yet, the message transmitted by Ameil was clear. It was up to Vetrov to find a way on his own to defect to the West, and he did not want to leave the Soviet Union. The man dispatched by the DST to handle him in Moscow did not seem to be an experienced professional. So, what to make out of all this? As a typical Russian fatalist, Vetrov had resolved on making do with what he had.

From the DST standpoint, the situation was more complicated.

In early 1981, the DST was still a service unfamiliar with fighting espionage by agents from the Eastern Bloc countries. The explanation of such a state of affair has its roots in history. Created in 1945 after the Liberation, the DST focused on tracking down former Nazi collaborators. After that, it had to turn its attention to subversive activities linked to decolonization wars in Indochina, in Algeria against the FLN (the Algerian Liberation Front), and against the OAS, a French anti-independence terrorist organization. During this entire period, it was usually the American secret service who was in charge of intelligence gathering about KGB activities in France, keeping the French authorities informed on a regular basis. It is undoubtedly the good relations between the DST and its American colleagues built at that time that would play a role later in the Farewell affair.

It was only at the end of the sixties and in the early seventies that the DST started in earnest to develop counterintelligence strategies against Eastern Bloc secret services. The DST, however, was not qualified to handle agents or implement active measures outside of France. It had no presence at all in Moscow, and neither did French intelligence.

The office of French intelligence that existed at some point in the Russian capital (usually staffed by two or three persons) had been closed down by Alexandre de Marenches, director of the agency called the SDECE at the beginning of the seventies. Although an authorized and credible source claims that French intelligence kept handling Russian agents during their trips outside of the Soviet Union, France gave up secret activities in its main enemy’s territory. The whole thing seemed so ludicrous at the time that the KGB launched a gigantic investigation to clarify the situation. After two years of relentless checking of operations, Soviet counterintelligence had to conclude that the SDECE had withdrawn, a consequence of the draconian Soviet police state.

With respect to military intelligence, an area in which the French had the reputation of being among the best, there was at the French embassy in Moscow a station of the Deuxième Bureau (Second Bureau of the General Staff), the official name of which was the Office of the Military Attaché. The Deuxième Bureau officers were not better equipped than the DST when it came to carrying on complex and delicate operations such as agent handling. Furthermore, what service would give up such an exceptional and promising case to a rival?

There is another important point. Unlike the foreign intelligence service (SDECE), the counterintelligence DST came under the authority of the Ministry of Interior, not the Ministry of Defense. It was staffed by police, not military personnel. Its culture, mindset, and methods were inherited from managing police informants. The “cousins,” as they were called in France, used to move in their own milieu in all independence, making decisions at their own risk, without reporting to anyone—a type of profile that, oddly enough, looked very much like Vladimir Vetrov’s.

So, in March 1981, there was the DST who inherited the treasure recovered by Xavier Ameil in Moscow, faced with a substantial double challenge. One was strictly operational. As mentioned, the service had no experience whatsoever in manipulating agents abroad since the legal framework of the DST’s activities was limited exclusively to the French territory. The other challenge was more political. The affair occurred in the middle of the French presidential election campaign, immediately after Ronald Reagan was elected in the United States, an event cooling East-West relations.

Two men handled these two challenges, each with his own style and personality. They were Chief Inspector Raymond Nart and his superior Marcel Chalet, director of the DST.

In 1996, both men refused to be interviewed by Sergei Kostin for the first version of this book. It was only in 2003 that they talked with Eric Raynaud about some aspects of the affair that remained unclear.

When Raynaud met them in a café near the Hôtel de Ville, he was struck by the perfect casting of characters their association formed. They seemed both taken directly from a detective movie made in the seventies, each playing in a style distinct from the other, yet perfectly complementary. Marcel Chalet projected the image of a subtle and cultivated man, expressing himself in extremely refined French and anxious to never contradict his interlocutor. Passion for secret action could pierce through the veneer of good manners, of course, but moderation was back in full force the minute the conversation moved on to the political dimension of counterintelligence activities. Raynaud was then face to face with a ministry-level official, totally at ease with those in high places. To Raymond Nart, who hardly hid his admiration for his boss, Marcel Chalet was the “classy” type.

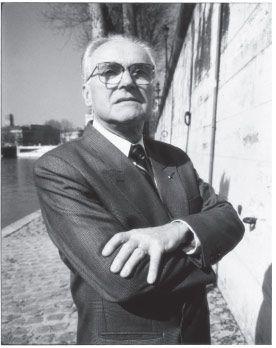

Marcel Chalet, the head of the DST. He skillfully managed the political aspects of the operation with the new socialist team in power as well as with the CIA.

For his part, Raymond Nart had clearly the profile of a true cop on the beat. Crafty, he came across as an expert in operations of all kinds. In the murky world of espionage it seems, however, that Nart’s most important quality was to remain direct and methodical, and always go for the simplest solutions. This inspector was obviously not inclined to speculate for hours about the ins and outs of a case. When Eric Raynaud asked him about one murky point of the operation and suggested some elaborate answer, Nart merely gave him a benevolent smile, saying that the truth is much simpler, and “it is precisely because we kept it simple that it worked.”

Things did not seem so simple, though, when he first received the assignment. As incredible as it is, when Raymond Nart received Vetrov’s two “life and death” messages, he was almost totally alone in the service due to exceptional circumstances. His direct superior Désiré Parent, deputy director of counterintelligence, was away, and Marcel Chalet was in the hospital. It was, therefore, on his own initiative that he decided to respond to Vetrov’s SOS, and “recruited” Xavier Ameil to begin the operation. Who at the KGB, the world’s most feared secret service, could have imagined that at that very moment they had only one lonely man facing them? The situation lasted several weeks.

When he recalled those first moments of the operation, and the potential for a deception campaign mounted by the KGB, Raymond Nart, with a dry voice and his lilting accent from southwest France, explained the situation. “In this service, where you did not have to report to anyone, you could beat about the bush for years. I had no intention to ask a minister if I needed to wait for a third signal.”

1

There was no possible comparison between the DST and “superpowers” such as the CIA and the KGB. Its limited staff made simplicity a material necessity considering the disproportionate strength of the forces facing one another. As in the story of David and Goliath, in unbalanced confrontations, the weakest has to outsmart the strongest.

By accepting transmission of the documents without hesitation, the amateur Ameil allowed the DST to skip a step. Raymond Nart did not really have to weigh the pros and cons, he did not have to ask himself if it could be a setup by the KGB, nor did he need to ask Vetrov for proof he was acting in good faith. As will become obvious soon, the value of the information received spoke for itself.

Although a legalist in principle, Raymond Nart was very aware that the service sometimes had to flirt with judicial limits, and that secrecy required a few transgressions. By operating outside of France, the DST had crossed a line, leapfrogging the SDECE, which had sole authority to deal in foreign countries. As happened many other times during his career, Raymond Nart preferred addressing his responsibilities “and facing up to them in case of failure” in contrast to prevaricating and submitting the matter higher up to cover himself.

In fact, it would be ridiculous and unfair to reproach the DST for having gone beyond the limits of its jurisdiction. Some missions cannot be accomplished within a strict limitation of time or space. In spite of its regulatory status, the DST had available contacts outside the French territory, notably in the French embassy in Moscow, including the office of the military attaché. The fact that Raymond Nart thought of Patrick Ferrant for the mission, a man he knew personally, cannot appear fortuitous.

Back to March 1981. With the arrival of the first shipments from Xavier Ameil, Raymond Nart, still on his own, decided to work with a colleague, Jacky Debain, and engage a translator, closeted in an office, to translate the huge volume of information received. For the entire duration of that period, his constant concern was to involve as few individuals as possible. “One is fine, two is borderline, three is a crowd.” The team worked relentlessly; the translator delivered ten pages a day, having no clue about where the documents were coming from. The stack kept growing, and Nart was anticipating with the utmost satisfaction the surprise he was preparing for Marcel Chalet.

A little while later, as soon as he came back from his sick leave, Chalet had a phone call from Nart asking if they could meet.

“Is it serious?” asked Chalet.

“Not at all,” answered his subordinate, with as detached a tone as possible.

Flanked by his two collaborators, Nart walked into Chalet’s office and, solemnly declaring “on this red-letter day,” placed a three-hundred-page stack on the desk, adding, “every single one coming from the KGB inner sanctum.”

“Are you kidding me?” asked Chalet, astonished.

“I wouldn’t dare, sir,” answered Nart.

Still shocked, the DST boss immediately suggested the risk of a KGB deception, but Nart had no difficulty, with the pile of documents in front of them, in convincing Chalet that the amount of information received to date ruled out such a possibility. “It would have taken a team of about eighty people doing just that, like an entire network, while sacrificing countless agents that had been patiently recruited. Impossible.”

Quickly convinced of the importance of the case, Marcel Chalet was nevertheless wondering about the political aspects of this affair. The elections were around the corner. France would have a new president in two months. In case of a left-wing victory, there would be a new government, a new administration, and consequently new actors to let into the secret—a multiplication of participants which the DST boss strongly disapproved of, not because of their political affiliation, since Chalet considered himself first a civil servant, but for a strictly technical reason.

“Why take the risk to talk about the case with the team now in place, at a time when it might soon be swept away? I thought it was not urgent to talk about it because, from that very moment, the main point was the necessity to preserve an exceptional source at all cost,” he explained.

2

Marcel Chalet carried professional ethics to the point of prohibiting Raymond Nart from revealing Vetrov’s identity to him, so he would not be able to tell his superiors about it in case they would ask.

The director of the DST thus decided to wait until after the elections to inform his future superiors. In the meantime, with his assistant, he focused on the operational aspects of the case.