Farewell to Fairacre (6 page)

Read Farewell to Fairacre Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Country Life, #Fairacre (England : Imaginary Place), #Country Life - England, #Fairacre (England: Imaginary Place)

'You are well, I hope,' went on the vicar, turning in his seat to study me anxiously.

'I'm fine,' I said firmly. 'Right as a trivet, whatever that may mean.'

'Good, good! Can't have you under the weather, you know. It's a miserable time of year.'

'I'll run you back,' I said. 'The rain's getting heavier.'

We trundled through the gathering gloom of a November afternoon, and I dropped him at his front door, refusing his kind invitation to tea.

Driving under the dripping trees to Beech Green, I pondered on this recent display of concern for my health.

Maybe I should get an iron tonic, as Amy had suggested.

The thought was disquieting, but I put aside my health problems after tea, and bravely settled down to some of my growing pile of paper work.

I found it heavy going, and by seven o'clock I was beginning to wonder, yet again, if all these questionnaires and forms were really necessary.

While I was looking back to the relatively free-from-form days of yesteryear, in a nostalgic mood, Amy rang to enquire after my health.

'What about that iron tonic? Have you seen the doctor? Are you sleeping and eating properly?'

'Oh, Amy!' I cried. 'It's sweet of you to be so concerned about me, but I am perfectly healthy. Simply lazy, that's all.'

'Well, I don't believe that, and all I wanted to say was that I hope you will come for a weekend soon, and we can see that you get a proper rest and some food.'

I began to feel like a victim of some national catastrophe being rescued by the Red Cross from starvation, homelessness and disease.

'What are you doing now?' queried Amy.

'Filling in quite unnecessary forms which should have been at the office last week.'

'That's no good to you,' said Amy firmly. 'Put them away, have a tot of whisky and go to bed.'

'I don't like whisky.'

Amy tutted impatiently. 'Well, hot milk then. With perhaps a raw egg in it.'

'It would go down like frogs' spawn! I couldn't face it.'

'What a tiresome girl you are! Anyway, take things quietly, and do let us know if we can do anything. Think about a weekend here. Any weekend suits us, except the next one. I've Lucy Colgate coming for the night, and I don't suppose you want to meet her?'

'Definitely not,' I agreed. Lucy Colgate had been at college with Amy and me. Amy, being of a more kindly disposition, had kept in touch, but I had always found Lucy pretentious, self-centred and irritatingly affected. I found that a little of Lucy's company went a long way.

'But thank you, my dear, for thinking of me, and I'll look forward to a weekend at Bent with enormous pleasure.'

After promising to eat, sleep, take iron tablets, consult my doctor in the near future, put my feet up whenever possible, and to Keep in Touch, I put down the receiver and went to feed Tibby.

The next morning my alarm clock failed to go off, and I awoke twenty minutes later than usual to a dark wet day.

Hurrying to the bathroom I noticed a heaviness in one foot, and supposed that I had been sleeping with it trapped under me.

Stumbling about, getting dressed, I felt annoyed that my foot and leg were taking so long to return to normal. However, there was absolutely no pain, and by the time I had snatched a hasty breakfast of cornflakes and a cup of coffee, I had forgotten the discomfort. It would wear off, I told myself, when I found that I had a slight limp on my way to the garage.

I drove to school determined to ignore a certain numbness in my left foot when using the clutch. Time to worry when something hurt, I told myself, and before long was so immersed in my school duties that I really did forget the trouble with my foot.

Preparations for Christmas were already starting, and Mrs Richards and I had decided that it was a year or two since we had embarked upon a nativity play, and that this Christmas we would produce a real masterpiece.

We had a number of Eastern costumes and various other props in a large box. We also had three shepherds' crooks which were stored in the overcrowded map cupboard along with rolled-up aids to education with such outdated labels as 'The British Empire 1925' and 'Aids to Resuscitation 1940'.

The vicar was enthusiastic about this project and invited the school to perform in St Patrick's chancel one afternoon towards the end of term.

'I think we might even have a collection. I'm sure that lots of parents and friends of the school would like to contribute to the Roof Fund.'

On this particular afternoon Mrs Richards and I took the children across to the church for a preliminary assessment of this natural stage offered to us.

The church was unheated, and uncomfortably dark and dank. I sat with the older children in the cold hard pews whilst Mrs Richards was busy positioning her children around the imaginary crib in the chancel.

As well as the physical discomfort I felt remarkably tired, and could have nodded off if I had been alone. It seemed a long time before Mrs Richards had arranged her groupings to her satisfaction, and I was glad to stir myself to take her place with my own class.

In the gloom I stumbled on the chancel steps but saved myself from falling by grabbing a choir stall.

We went through this first tentative rehearsal of positioning and then decided that it was too cold to linger. On our way back, Bob Willet hailed me from the churchyard.

'All right to bring you up some keeping apples?' he called. 'Alice's sister's given us enough for an army, and I've got to come your way after tea.'

I said that would be fine, and we made our way back to school.

'You're limping,' said my assistant. 'What's wrong?'

I told her about my numbed foot.

'Surely it shouldn't be

numb

for hours!'

'Well, sometimes it

tingles,'

I assured her. 'It's nothing. It doesn't hurt.'

'I should see the doctor,' said Mrs Richards.

'I should see the doctor,' said Bob Willet, when we were sitting at the kitchen table later that day.

He had watched me pouring tea into two mugs, and commented on my shaking hand.

'It's nothing,' I said shortly. I was beginning to get rather cross with all this advice. First Amy, then Mrs Richards, and now Bob. 'The pot's heavy, that's all.'

'Well, I've seen you pouring tea for years, and never seen you wobblin' about like a half-set jelly afore.'

'Those apples,' I said, nodding towards the box he had brought, and keen to change the subject, 'are more than welcome. Will they keep all right in the garden shed?'

'Wrapped up in a half-sheet of newspaper,' said Bob, 'they'll be sound as a bell till after Christmas.'

He finished his tea, and I bade him farewell at the door. The rain still pattered down, the trees dripped and the ground was soggy.

I returned to the kitchen. Should I wrap the apples now, or get on with the children's personal records as requested by the office?

Frankly, I felt too tired to face either. I leafed through the

Radio Times,

and was offered 'Sex Slavery in Latin America', a modern play described as 'explicitly sensual', or a quiz game which I knew from experience plumbed the depths of banality, to the accompaniment of deafening applause from the captive audience.

I cast the magazine from me, and eyed Tibby, blissfully asleep in the armchair.

An excellent idea, I thought, and went upstairs to my own bed.

The rain had stopped when I awoke next morning, and I told myself that now all would be well after such a long and deep sleep.

My foot still hampered me, and I had to admit that I was wobbling 'like a half-set jelly' as Bob Willet so elegantly put it. Perhaps I really ought to visit the doctor? The prospect was depressing.

Not that I had anything against the young man who was one of several who had come after our well-beloved Dr Martin who had died, but I did not relish spending part of my evening in his company. At least, I thought hopefully, as I drove to school, it would mean postponing those wretched personal records that were beginning to haunt me.

The vicar came to take morning prayers, and said when he left that I looked rather tired and that he hoped that I was not over-doing it.

Mrs Richards insisted on pouring the hot water into our coffee mugs at playtime as she could see that I was 'not quite right yet'.

Mrs Pringle, arriving to wash up after school dinner, said that her aunt, although a strict teetotaller, had 'staggered about' just as I was doing, 'looking as drunk as a lord'.

Joseph Coggs, who kindly accompanied me to my car at home time, carrying yet another heavy file of papers, said that his gran 'walked just like that, all doddery-like'.

I decided that it was high time to visit the doctor.

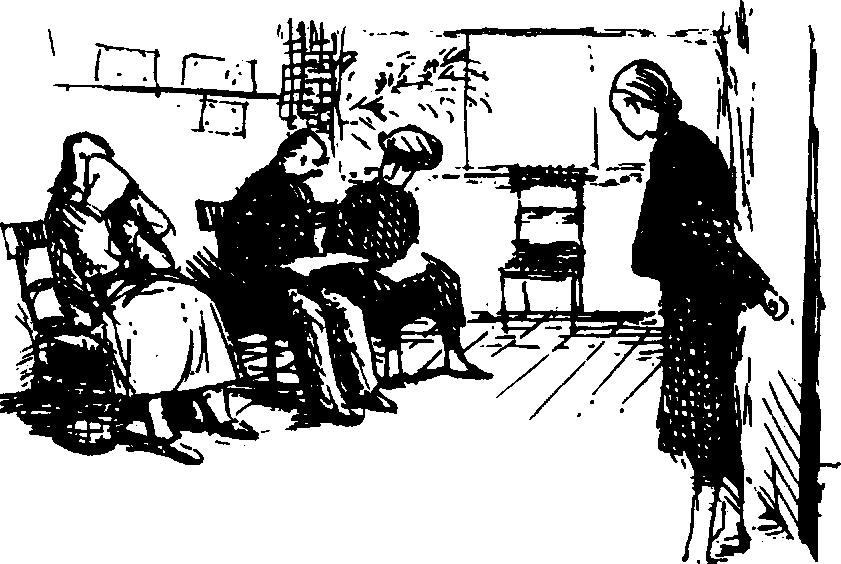

There were only four of us in the waiting-room, the other three unknown to me. One had an appalling cold which needed noisy attention into dozens of tissues which she stuffed after use up the sleeve of her cardigan. I did not feel that this was very hygienic, especially as a wastepaper basket stood nearby. However, I thought charitably, the germs were being kept closer to her own vicinity by her present method of disposal.

The other two were obviously a married couple, passing magazines to each other, and occasionally speaking in a hushed tone as if in the presence of the dead.

I helped myself to a magazine which soon posed some problems for a respectable single woman.

Question: Was I worried about my present sex life?

My answer: Not in the least. But nice of you to ask.

Question: Was my doctor sympathetic to my sex problems?

My answer: No idea. In any case I should not be troubling him with such matters this evening.

I got up to change this magazine for an ancient

Homes and Gardens,

which surely should provide more acceptable reading matter, when the door opened and I was summoned into the presence.

I knew Dr Ferguson slightly, and he was pleasantly welcoming. I explained my symptoms in unmedical terms, and he listened attentively.

After some questioning about my family history, he took my blood pressure and pulse, listened to my chest with an ice-cold stethoscope, and then said, 'There's nothing to worry about. I think you have simply had a very mild stroke.'

'Nothing to worry about?' I squeaked in horror. 'A stroke?'

'Not if you are sensible. Lots of people have slight strokes. There is no pain usually, and after a day or two one is over it.'

'But suppose I get a

bad

stroke? What can I do to stop any sort of stroke?'

I must admit that I was feeling thoroughly shocked by his diagnosis. Me, a stroke? It was unthinkable!

'The first thing to do is to face this calmly. It is not serious. It is simply a warning. Your body is telling you to avoid any sort of strain, mental and emotional as well as physical.'

I thought of my daily encounters with Mrs Pringle, and reckoned that my emotional strain, in just that one quarter, must be excessive.

'You are in sound health, except for slightly high blood pressure. I'll give you some tablets for that. The only advice you need is something you know already. Rest as much as possible, keep to a sensible diet, and

don't worry\

Come and see me in a week's time.'

He scribbled a prescription, handed it over and I rose to g°-

At the door I turned.

'You know I am a teacher. Am I likely to have the sort of stroke that would knock me out in front of the children?'

He looked at me soberly, considering my question seriously, and I liked him for that.

'It is not likely, but it cannot be ruled out entirely.'

'Thank you,' I said, and tottered out to my car.

I could not get to sleep that night.

I have been exceptionally fortunate in having good health, and rarely had to take time off from school. One takes such a happy condition for granted until some blow, like this one, makes one realise that the body gives way occasionally.

My last question to Dr Ferguson had been the outcome of my main worry. I remembered, with painful clarity, the scene in the infants' room so long ago when Dolly Clare had collapsed.

She had been smitten with a heart attack, and had fallen forward across her desk. Her white hair lay in a puddle of water from an overturned flower vase. Her lips were a frightening blue colour and her eyes were closed. Gathered round her were a dozen or so terrified children, some in tears, and it had taken me some time to collect my wits and hurry them to my own room while I attended to the patient.

The incident had shocked me deeply, and had never been forgotten. Now I was facing a similar problem.

Here I lay, in Dolly Clare's bedroom, wondering what to do. Had she felt as I did now, shaky and full of doubts?

Dr Martin had told me on that dreadful afternoon that she had suffered one or two earlier attacks but had refused to give in. Would the same thing happen to me? Should I collapse as she did in front of a class of horror-struck children?

And what sort of state should I be left in? I thought of several people who still suffered from the effects of a stroke. Some were speechless, some were immobile, some were mentally affected. Was that to be my future too?