Farewell to Fairacre (9 page)

Read Farewell to Fairacre Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Country Life, #Fairacre (England : Imaginary Place), #Country Life - England, #Fairacre (England: Imaginary Place)

Very appropriate, I thought, wondering what the future held for me.

I must have dropped off for when I awoke I heard Mrs Pringle talking to someone in the kitchen.

'I thought to myself, "Well, Maud, if you nip into Caxley on the eleven, you can get the slippers at Freeman, Hardy & Willis and the brawn at Potter's for Fred's tea and catch the two o'clock back to Miss Read's for the brights.

'But that skylight was a blessing in disguise this time. "Best report that, I thought, and no time like the present," so I got off here and lucky I did.'

'It was indeed.'

I recognised Isobel Annett's voice.

'And there she was laying,' went on Mrs Pringle, (eggs or bricks, I wondered?) 'and my heart turned over. I thought she'd passed over, I really did.'

'I must see her,' said Isobel. 'Is she upstairs?'

'On the couch,' replied Mrs Pringle, sounding somewhat offended at being interrupted in her dramatic monologue.

Isobel came in, followed by Mrs Pringle. I had closed my eyes hastily. I could hear Mrs Pringle's breathing.

'I think we should get her to bed,' said Isobel.

I opened my eyes, and nodded, not daring to speak.

'Can you manage it?' asked Isobel, putting an arm round me. I nodded again, and we tottered entwined to the stairs, followed by Mrs Pringle.

'Could you make a little bowl of bread and milk?' asked Isobel. 'I think she might manage that.'

Mrs Pringle, debarred from the pleasure of undressing me, retired to do her allotted task.

She was limping heavily, I noticed, but was too concerned with my own troubles to worry much about it.

Dr Ferguson arrived and was reassuring.

'Luckily you haven't broken anything in the fall. And this is just another warning, like the first. It's simply hit other senses this time. I think your speech will be much better by the morning. The worst thing is this bang on the head, but it's coming up nicely.'

He fingered a lump on the right-hand side, making me wince.

'Stay there,' he told me, 'and I'll pop in tomorrow morning after surgery.'

I heard his car drive away. Some time, I thought dazedly, I should have to make all sorts of decisions. But not now. I was too tired to bother.

I turned my aching head upon the pillow, and fell asleep.

Amy came to look after me for a day or two, and then bore me back to her house at Bent with Dr Ferguson's blessing.

Normal speech returned within three or four days, and apart from the lump on my skull which diminished daily, and the overpowering feeling of exhaustion, I felt much as usual.

I wrote to thank Mrs Pringle, and also spoke to the vicar, telling him that I hoped to be fit to return to school as soon as term began. According to the doctor I had suffered from mild concussion, after my headlong collision with the cooker, as well as the second stroke which had triggered off the chain of events.

It was fortunate that all this had occurred in the holidays, but I had plenty of time, as I pottered about at Amy's, to consider the future. I had been given two 'warnings', as the doctor called them, in as many months. I had been lucky to get away with only a bump on the head as a secondary injury. As Dr Ferguson had said, I could have broken a leg or hip as I fell.

Memories of Dolly Clare's classroom collapse so long ago, and visions of other victims of strokes, all came to haunt me. My old dread of such an attack happening at school, in front of the children, was my chief anxiety, and I admitted this to Amy one quiet evening as we sat knitting by her fire.

I had marvelled at the way she had refrained from scolding me throughout her invaluable nursing, but now, confronting my fears, she spoke in her usual decisive manner.

'It's time you packed it in,' she said. 'I know you've only about two years to do, but whatever's the point in knocking yourself up, and starting retirement as an invalid?'

I said that the doctor had assured me that I should re-cover.

'He said that the first time,' retorted Amy, 'and you say yourself that you felt quite well, and did all the things he had told you, but even so you've had this second attack. To my mind, it's a more severe one. And with your speech affected what good would you be as a teacher?'

The same dismal thought had occurred to me, of course.

'Would you be terribly unhappy if you gave up your job?'

'I'd miss the children. But no, on the whole I think I'd enjoy being a free woman.'

'Have you got enough to live on? Would you have to wait to get your pension?'

'I've got quite a bit stashed here and there, and I'd have to find out more about the pension. I think I might get it immediately, but in any case, I can get by.'

'Well, James said that I was to tell you that we can tide you over, and you are not to worry.'

'James,' I said, 'is an angel in disguise.'

'Pretty heavy disguise too,' said Amy drily, 'when his breakfast's late.'

We shelved the problem of my future, and had a glass of Tio Pepé apiece.

A few days before term began I returned home. I felt strong enough to face the rigours of school and my own simple house-keeping. Tibby was somewhat stand-offish, as might be expected, but came round after an extra large peace offering of Pussi-luv.

My first visit was to Mrs Pringle to present her with a china cake dish she had admired in Caxley, and had described to me some weeks before.

A rare smile lit up that dour face when she undid it, and I renewed my thanks for her timely help.

'I truly thought you'd gone,' she told me. 'Like a corpse you lay there, and I was going to straighten your limbs before they stiffened, when you gave a groan.'

'That was lucky,' I commented.

'It certainly was! That's when I heaved you on to the couch.'

'You were more than kind. And now I must be off.'

It was plain to me, as I met one or two old Fairacre friends in the village, that my stroke had been well documented.

Mr Lamb at the Post Office shook my hand, and said it was good to see me back. He did not actually add 'from the dead', but I sensed it.

Jane Winter, one of the newcomers, said, 'My goodness, I didn't expect to see you looking so well!'

Joseph Coggs, playing marbles outside the chapel, said he thought I was still in hospital because I'd been struck dumb. Mrs Pringle had said so to his auntie.

I replied in clear and rather sharp tones.

Mr Willet emerged from his gate, and entreated me to come in, to sit down, to give him my coat, and to have a cup of coffee which Alice was just making.

I accepted gratefully.

'Well,' said Bob, as we sat at the kitchen table with our steaming mugs, 'I didn't believe half what Maud Pringle said, but we was all real scared to hear the news.'

'Not as scared as I was,' I told him. 'I'm not used to being ill.'

'You take care of yourself,' said Mrs Willet. 'We don't want anyone else in your place at the school. Everyone was saying so, weren't they, Bob?'

'So what's the news?' I asked hastily, changing the sub ject.

'Not much. Except for Arthur Coggs.'

'I thought he was safely in prison.'

'He come out about a fortnight ago. You know how it is these days. These villains get sent down for six months, and they're out again before you can draw breath. Remission, or some such. Anyway, he's out, and got one of his religious turns again.'

'Oh dear!' I exclaimed. We all know what havoc Arthur Coggs' religious turns can cause. On one occasion he had knocked up the Willets when they were asleep, and filled with burning zeal and too much strong beer had attempted to save their souls.

On another occasion he had entered the church during Evensong and started a loud tirade, punctuated with inebriated hiccups, on the after-life of those present in the congregation. Two sidesmen had removed him to the churchyard, but not before he had overturned a pot of gladioli in the church porch, and ripped a warning about swine fever from the noticeboard hard by.

On the present occasion evidently he had trespassed into the Women's Institute meeting at the village hall, whilst the members were engrossed in a cookery demonstration.

The demonstrator was a young woman with little experience. She was nervous before the twenty or so elderly women, who sat clutching their handbags on their laps and watching the proceedings with critical eyes. Her employers, a firm of flour manufacturers, had given her a course in pastry-making of all types, and this knowledge she was now imparting to her audience.

She had spent some time showing them different sorts of flour in half a dozen small bowls, and then continued with the making of choux pastry, puff pastry, and hot-water pastry for raised pork pies and the like. Whether she imagined that the women before her still ground their own flour from their harvest gleanings, no one could guess, but the rather condescending nature of her patter definitely irked them.

Had she but known, nine out of ten of those present had long ago given up making their own pastry, and rummaged in the local shops' refrigerator cabinets for nice ready-made packets marked 'shortcrust' or 'puff', and with no sticky fingers or mixing bowls to worry about.

It was while the earnest young woman was attempting to raise hot-water pastry round a jam jar that the interruption occurred.

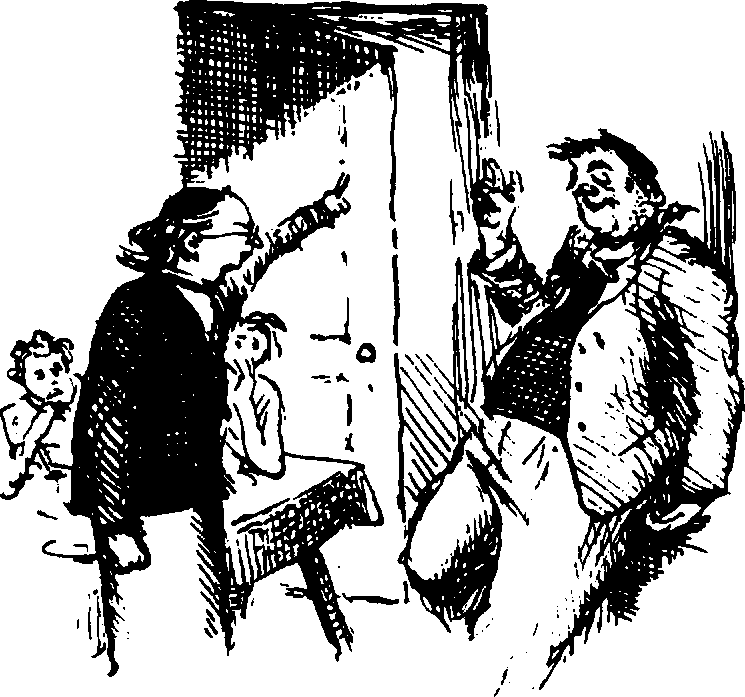

It was not entirely unwelcome. The tea ladies were already beginning to whisper to each other about switching on the urn, when the door from the kitchen burst open, and Arthur Coggs, clearly the worse for drink, stumbled into the hall.

He approached the table unsteadily. The demonstrator, with a squeak of panic, retreated behind it, floury hands to her face in alarm.

'Get out, Arthur Coggs!' shouted one brave woman, but was ignored.

'Ish thish,' demanded Arthur, 'the 'all of shalvation?'

'No, it isn't,' said Mrs Partridge, the vicar's wife, coming forward to take charge as president. 'This is the village hall, and well you know it. Go home now!'

Arthur turned a bleary eye upon her. He put one hand on the table to steady himself, and smacked it down upon a wet mound of pastry.

'I've seen the light,' he began, amidst outraged murmurs. 'I bin a shinner, but now I'm shaved. And I'm going to shave you lot too.'

'Oh, no you're not, Arthur,' said Mrs Partridge firmly. 'You are going home, or we shall send for the police.'

She attempted to edge him towards the door. A large dollop of pastry fell to the floor, and was flattened under Arthur's boot.

'My pastry!' wailed the demonstrator, bending down to rescue it. The table gave a lurch from the activities around it, and the jam jar with its skirt of raised pastry rolled to join the mess on the floor.

'The police?' echoed Arthur. 'They needs to shee the light too.'

At this point, three more women came to Mrs Partridge's aid and manhandled the protesting saviour-of-souls into the kitchen.

'I'll just switch on while we're here,' said one, eminently practical, despite holding one of Arthur's ears.

Protesting vociferously, Arthur was bundled through the back door.

'I gotta meshage for you,' he shouted, 'a meshage from the Lord!'

'Well, you'd better go and tell the vicar,' replied Mrs Partridge, giving him a final push.

They slammed the door and bolted it.

'The idea!' puffed one.

'He ought to be put away!' said another.

'Won't the vicar mind?' queried the third timidly, as they went back to the hall.

'He can cope with Arthur,' replied Mrs Partridge. 'I have the WI on my hands.'

She swept in like a triumphant general at the head of his troops, and was greeted with cheers.

The New Year opened with a bitter wind blowing from the east.

The ground was iron-hard and white with frost until mid-morning. The ice on puddles scarcely had time to unfreeze during the day, before darkness fell at tea time and the temperature plummeted again.

Tibby and I went out as little as possible. Indoors we were snug enough, for the fire burned brightly in this weather, and my new curtains kept out any draughts after nightfall.

I had plenty to do indoors. There were always school matters to deal with, as well as domestic jobs over and above the usual daily round. I turned out a store cupboard, marvelling at the low prices I had paid only a few years earlier, and even came across a tin of arrowroot which bore a label for one and ninepence. After such a length of time, the contents were given to the hungry birds. They appeared to be delighted with this vintage bounty.

As the first day of the spring term grew closer, I gave more and more thought to the future. Amy's advice about retirement was sensible, I realized, but it seemed so terribly

final

, the end of my useful life, so to speak, and with what would I fill my days?

On the other hand, was it fair to the school to struggle on with this constant dread at the back of my mind? I should not be the woman I was before these attacks, and I was reminded again, most uncomfortably, of the abilities of the new children in comparison with the indigenous Fairacre pupils whose accomplishments were not so high. Was it my fault? Were my teaching skills waning as I grew older? Was I pulling my weight?