Farm Girl (2 page)

Authors: Karen Jones Gowen

Tags: #Sociology, #Social Science, #Biographies, #General, #Nebraska, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rural, #Farm Life

Then while taking a folklore class at Brigham Young University, I learned how to interview and collect information for a folklore study. For one assignment, I interviewed Mother to get her memories of the Dust Bowl days in Nebraska. A folklore study differs from most writing, in that the tale is told in the voice of the individual telling the story, not by the collector. Finally I understood that the story I had always wanted to write must be told in her voice, not mine.

Farm Girl

is written by me as folklore collector rather than by me as author.

I spent many hours collecting the information, typing as Mother opened up her very extensive memory bank. What an exciting endeavor! Finally I was getting the authentic account of the Marker farm, her childhood, the New Virginia community and country school, and a glimpse into her high school years in Lincoln. Even the many aunts, uncles and cousins eventually got straight in my mind and became real characters. Before this, they were unknown, distant relatives who came up now and then in her conversation. Except for Aunt Bernice and Uncle Ford, who were part of our childhood like Grandma Marker and the old farm itself. Best of all, through collecting these memories, I became acquainted with my grandfather John Marker, who died when I was a toddler.

The advantage to this book being

told

by Mother rather than

written

by her, is that when she recalls her early years, she talks like Lucille Marker the Nebraska farm girl; but when she writes, it is Mrs. Jones, the English teacher. Despite the opinion of her senior English teacher, Miss Elsie Cather, my mother is a wonderful writer who clearly and concisely creates a picture with words. However, I wanted her memoir in her true voice as a farm girl rather than that of a highly-educated English teacher. To accomplish this, it was essential that she tell her story rather than write it.

A disadvantage of the telling is that it doesn’t come out in a nice, readable narrative form; one’s memories don’t usually organize themselves like that. It required many more hours of editing and arranging to create a story with a beginning, a middle and an end. And once I was familiar with her voice, I could occasionally depart from my role as collector and take some license as an author, adding here and there to fill in story gaps, yet maintaining the voice of the farm girl, Lucille Marker.

The Endnotes after the text are the dates, facts and additional information Mother provided that might be interesting to a reader but couldn’t fit into the narrative.

Julia Marker, Lucille’s mother, was a gifted, self-taught artist and writer, evoking emotion and creating an image with words as effectively as she did with brush and canvas. She had been painting for many years when, in 1948, she decided to try writing. She saw how rapidly American life was changing post-World War II, and she wanted to record the story of the Nebraska homesteader as she remembered it.

Julia Marker’s written memories and stories of her childhood on the homestead in the 1890’s and her life as a farm wife are included in Appendix B, as well as photos of several of her remaining paintings. The entry about the early homesteaders is written from stories told to her by her father Hans Walstad, who came to Nebraska in 1870.

Many thanks to the Wido Publishing team for their extensive skills in printing, designing and editing; and for their willingness to contribute their time and talents to help create this book.

—Karen Jones Gowen

February, 2007

Oil painting of a sod house by Julia Marker

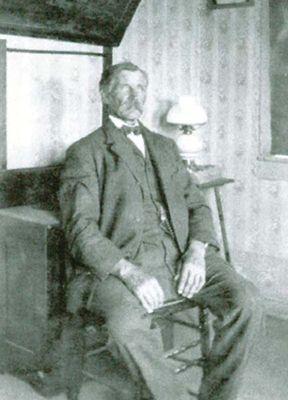

Hans Walstad

My grandfather Hans Walstad lived alone in a dugout near Farmer’s Creek, back when cottonwood, elm and ash trees crowded the banks. Lots of fruit grew near that creek—grapes, plums, chokecherries, berries. Indians would come by his dugout and want tobacco and sugar, and he’d trade with them for buffalo meat and furs. Somehow they communicated, by signs I suppose, because he spoke only Norwegian. He was one of the first settlers to stake a claim in this part of Nebraska.

Hans would have stayed forever as a single man in his dugout because the girl he had loved back in Norway had married another man. Her name was Sofie Maren Stav, and she chose to marry Andre Pederson rather than him. So Hans decided to come to America and homestead in western Nebraska and live by himself in this dugout. He was happy here and had everything he needed. Soon his parents, one brother and three sisters came to the area and settled nearby, so he wasn’t at all lonely.

His parents, Jakob and Karen Walstad, left Norway when Karen was 72 and Jakob 67, to be with their children in America. The older couple wanted a log house like they had in Norway rather than a sod house, so they cut logs from the trees along Farmer’s Creek and built a house across the draw from Hans.

The young woman, Sofie, who Hans had loved, and her husband Andre Pederson, had been neighbors to the Walstads back in Norway. So many of their friends and neighbors had left for America, and Sofie and Andre decided to come as well. They came in 1865 and settled in Chicago, where Andre found work in an iron mill.

He would carry the hot molten iron in pails and not dare set it down or it would burn through the wooden floor. Two men would carry a large kettle between them, and sometimes their clothes caught fire when they poured the hot metal into the molds. Hundreds of people were employed in this foundry. Andre worked there from 1866 to 1870, when he contracted typhoid fever and died, leaving Sofie with their young son Anton.

Sofie worked as a tailor making men’s suits, only missing one day of work, the day her husband died. She was in Chicago when the great fire started in 1872. She lived in an apartment house several blocks from the river. She had all her belongings packed and ready to move out, but the fire didn’t cross the river.

That night people paraded up and down the streets, some in their night clothes carrying a single picture, or a looking glass. Half-crazed by fear of the fire, they just picked up anything and left their homes. Some carried bundles. No one knew where to go. The fire had destroyed their homes. The people who were fortunate enough to have their homes spared had to share them with the less fortunate. Two girls lived with Sofie for several years after the fire.

One summer in the early 1870’s, before the Great Chicago Fire, it was prophesied that the world would come to an end. People were supposed to meet Jesus in the park at a certain time and should be dressed all in white. It was on a hot, sultry afternoon, clouds were gathering and at the hour Jesus was to be there a rainstorm appeared with great force. Those who had not gone to the park were sure this was the end of the world.

Sofie had not gone, and she tried to comfort people, saying, “This is just a rainstorm, not the end of the world.”

Despite all this, Sofie liked living in Chicago and did well at her work, being a talented and capable seamstress. She and Anton lived for several more years in their apartment on 54 West Erie Street. The boy stayed with her when she worked, until he started school. After school, he’d be alone, buying food for dinner with the money his mother left for him on the table. She worried about him home alone, especially after he fell and broke his arm, and she worried that the city wouldn’t be a good environment for a boy to grow up without a father.

The summer of 1877, when Anton was eleven, Sofie left for the West, thinking the country would be a better place to bring up her son. She had written to Karen and Jakob Walstad, her former neighbors from Norway, and they invited her and Anton to stay with them out in Nebraska. She and Anton rode the train out with a girl she knew from Chicago. When they reached Hastings, they had to ride the rest of the way with the mail carrier, in the mail wagon.

The mail carrier told her, “Wherever you see smoke coming through the bank is where people live in a dugout.”

Hans Walstad lived right across the draw from Jakob and Karen, and now here was the girl he had loved in Norway so many years earlier living at the log house with his parents. They began to keep company again and soon were married.

Hans still lived in his dugout, a cave-like home that was made by digging out the earth in a hill, a bank or raised area on the prairie. These dugouts could be quite comfortable, with a front door and even glass in the windows. Early settlers usually lived first in a dugout, then would build a sod house, and then a frame house when they were able.

His new wife didn’t like the dugout, not wanting to live underground like a prairie dog, so she talked Hans into building a sod house. He was so happy to at last have Sofie as his wife, he would do whatever he could to please her. They worked together building the sod house.

The settlers used sod for their houses as trees were not so plentiful. The land had never been tilled, and the many roots from the prairie grass held the soil together. Homesteaders would cut a slab of sod one foot by three feet, laying three of them down like bricks with one foot on the outside and the other end on the inside. The next layer they’d lay the opposite direction with the three foot end out and the one foot in. This made the walls three feet thick, making them very warm in winter and cool in summer. The window sills were so wide that children could sit on them. Some were cemented on the outside and plastered on the inside, so if you didn’t know it was a sod house, you couldn’t tell. You couldn’t see the dirt.

Hans and Sofie raised Anton and had two daughters, Mathilde, the older daughter, and then Julia, born in 1882, who became my mother.

One day in 1896, when my mother was about fourteen, the family’s sod house was completely destroyed by a tornado. Here’s how it happened. They saw a tornado coming and ran to the storm cave. When it was over, they came out and saw one of their cows upside down on the ground, completely wrapped in twine.

Hans said to his younger daughter, “Go to the sod house and get me a knife.”

Julia replied, “There isn’t anything left there.” The tornado had taken the sod house, leaving only part of the walls.

He said, “Well, then, go get one from the log house.”

After the tornado destroyed their home, the family had to live with relatives until they could rebuild. By this time the grandparents, Jakob and Karen, had died and the roof of their log house was gone, so the Walstads couldn’t live there.

Eventually, like most homesteaders, Hans and Sofie were able to build a frame house. Finally they had a permanent home and a farm that did well, after surviving many hard years of drought, hailstorms and grasshopper invasions. Then, a few weeks after the older daughter, Mathilde, was married, Hans died. Sofie continued to live on the farm with Anton long after her husband died and both girls had married and left home.

Uncle Anton was a gifted musician who played the accordion. If he heard a song once, he could play it. He would play at dances, although his mother didn’t like that, so he wouldn’t tell her about the dances.

One time, when he was a young man working as a hired hand, he took ill and lost all the hearing in one ear and most of it in the other, but he could still play his accordion.

Uncle Anton loved to read, especially the newspaper. He took several Norwegian papers and also the Chicago Tribune, and could talk about current events. He’d save the funny papers for me and bring a whole roll of funny papers over to our house. I looked forward to that so much, and I’d lay on the floor reading them for hours.

He never married, because he had a large growth on his forehead that, along with his deafness, made him selfconscious.

My mother would drive our horse and buggy five miles west to see her mother and brother and take them food and things. I remember going along one time and seeing Grandmother Sofie in bed in a little room off the kitchen. She couldn’t walk very well when she was older. She was very hunched over because of being gored by a bull years ago and thrown over. It had broken her back, and she just laid on the couch for a long time until she could manage to get around.