Farm Girl (9 page)

Authors: Karen Jones Gowen

Tags: #Sociology, #Social Science, #Biographies, #General, #Nebraska, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rural, #Farm Life

I didn’t like to hear that language. Sometimes the other boys would swear when they were off together, but generally not in school.

But then a lot of the boys were kind of coarse, they were farm boys, and they called things by their common names.

One day a boy told about helping a calf being born that morning, when the dad had to stick his arm into the cow to pull the calf out. Sometimes they told jokes about kind of dirty things, not always farm things. I can still remember some of those jokes, but I don’t repeat them.

Fay Lovejoy was only there for part of a year, then he and his dad moved away. I was so glad I didn’t have to sit by him anymore. Boys wore their dirty farm overalls to school and sometimes stank like cow manure. But I was used to my dad’s dirty overalls and to the smells of farm life. That didn’t bother me like Fay Lovejoy’s language did.

I always had to wear long underwear folded over under my socks and long cotton socks up to my knees. A bunch of the older girls were talking about not wearing long underwear.

I wanted to be grown up like them, so I said, “Well, I’m not wearing long underwear either.”

They didn’t believe me, so they took me out by the outhouse and rolled my socks down to see if I had long underwear on.

They all laughed at me. “So much you’re not wearing long underwear! What’s that?”

I was so embarrassed and never wanted to tell lies after that.

Norma Lambrecht was two years younger than me and oh, she had the best lunches! I’d bring my gallon lunch bucket, a Karo syrup bucket, with a homemade bread and jelly sandwich, a piece of cake, sometimes a thermos with chocolate milk. Or I’d have a boiled egg and some meat wrapped up.

Norma had bought bread and bologna sandwiches, a cookie with marshmallow topping, things her mother bought in town, like bananas. I looked at those lunches so longingly.

That Lambrecht family had a lot of bought things. Norma’s mother was younger than mine and maybe she didn’t want to bake as much. And they had a lot more chickens than we did, to trade eggs for special things from the store.

The worst lunches belonged to Irving Brooks and his brother and sister. Their mother was very intelligent, directed plays, wrote poetry and read books. They’d have ugly bread, kind of gray and misshapen, and not much else in their lunch pails.

My mother always made nice big, white loaves of bread.

At lunch, the big girls discussed their weekends. “Hey, we went to the dance at the Bohemian hall Saturday night.”

The boys talked about horses and cows and helping their fathers. “Dad pulled the hay rack up to the feedlot, and I had to pitch it all by myself.”

Once in awhile someone would see a show or a movie and tell everyone about it. That was a big event.

One time Desco Lovejoy brought his cousin, Lawrence Lacour to school to visit. His dad was an evangelist preacher and his mother a Lambrecht. Lawrence was so handsome, with nice features and dark, curly hair, and very nice-mannered, a couple years older than me.

After that, I kept asking about him and hoped he’d visit again.

Outside the school, the fence around the pastures and the north field had thistles piled up about fifteen feet. We’d push them up a little bit and make a cave in there and play house like little girls do. We’d get boards and tree branches to prop up the thistles and have a little cave to play house.

Every now and then, a skunk went in and out through the hole in the foundation under the school. Sometimes in the mornings we smelled a faint skunk smell and knew it was under there. The boys put a trap near the hole in the foundation, and one morning when we got to school, the skunk was caught in the trap.

Francis tickled it with the stick, even though the teacher told him not to. He got sprayed and had to walk home alone, about 2½ miles. Oh, did it stink around there.

One of the older girls had perfume, so the teacher put some on a handkerchief and held that over her nose all day. Our teacher, Alice Whitaker, was a town girl from Red Cloud and not used to all the country things.

In 1926, they built the new school on the same land, while we were still going to school in the old one. The new one had a basement and two rooms on the main floor. They thought they might have ninth grade there but never did. The library was a third room, then there was a coat closet in the entry for the boys and a separate entry and coat closet for the girls. The basement had a furnace and another room for coal. The little ninth grade room had a stage, with folding doors that were almost always open. The stage was built up about a foot higher than the rest and we’d have programs there.

I started fifth grade in the new building. The seventh and eighth met together, fifth and sixth together, and third and fourth. First and second were together some of the time, but the first graders had to learn to read so their classes were often separate. One teacher taught all the classes. No teacher ever stayed longer than two years, hardly even a whole school year. Sometimes they left to get married or to have a baby. One teacher left early because she couldn’t keep discipline.

In fifth and sixth I sat and watched the seventh and eighth graders diagram sentences on the board and do their long division and fractions. Once I finished my work, I listened while the teacher explained lessons to the seventh and eighth graders. By the time I got to seventh, I knew how to do all their work. I loved to work at the blackboard and couldn’t wait for a chance to go.

About that time the Mattison kids, Myrna and Dallas, who lived up by Uncle Ford, didn’t want to play with me anymore. They were good friends of mine until sixth grade. Myrna played with Theola Lambrecht, and Dallas got to liking Theola. Those three teamed up against me that year and called me names.

Myrna was the worst. She’d sneak up behind me and say something mean, like “Red face!” because I blushed a lot.

Or she’d say “Smarty pants! Smart aleck! Think you’re smart don’t you?”

Pretty soon I stopped trying to be her friend and just kept away from her. We had been good friends before, but then she wanted to hurt my feelings every chance she got. I never knew what was back of it.

Then the Mattisons moved away, and I was glad. If we’d still been friends, I would have been sorry. I always liked Myrna’s brother Dallas, too. He had a round face, a pug nose and light brown hair. Myrna, Dallas and I had played together a lot growing up. The Mattison kids used to drive a cart with a Shetland pony to school in bad weather.

Most kids walked to school. On bad weather my dad took me on horseback, with me riding behind him, over the pasture and over the field, then I’d climb over the fence and run the rest of the way. Hardly ever did any cars come to school, unless there was a special occasion when someone had to leave early and their parents came by in the car to pick them up.

When it snowed we played Fox and Geese. You made a big circle with four crisscrosses in the center, like cutting a pie. In the center you were safe. Someone was the fox and chased everyone on one of the crisscross paths made in the snow. If the fox caught you, then you became a fox and you’d have to help him catch the others. The idea was to make everyone a fox. The winner was the last goose left when the bell rang.

Everybody played these games, the teacher, boys, girls, all ages usually played. Unless there were little ones too small to take part, then they’d play by themselves.

Another snow game was playing angel, making angels in the snow. Boys liked to make big forts and throw snowball fights. We had two fifteen-minute recesses and one hour at noon. There were twenty-six to thirty students all the time I went to school, with eight in my class.

A nice-weather game was hockey played in the dirt with sticks and tin cans. Another one was Pom Pom Pull-away. Kids lined up in two lines, we drew two lines in the dirt, 100 feet apart. The one that was It would call “Pom Pom Pull-away, if you don’t run I’ll pull you away.”

Everyone ran and whoever got caught was It, and they had to help catch the others. The last one caught was the winner. A game similar to that was Jail, where you lined up and had to run. When you got caught you were in jail. You had to go stand inside the square of the windmill, that was jail. The others who were free tried to touch the ones in jail and get them out.

There was farm machinery called discs, that in the spring was run over the ground to break it up for planting. Sometimes they would break or get dull, and then boys brought them to school to use for our bases. They made good baseball bases. They were about 18 inches in diameter, the sharp end would go into the ground so it wouldn’t slide.

The windmill at the school pumped water that ran slightly downhill a little ways. One Friday someone left the windmill on and it ran all weekend. The water kept on running down the hill, under the fence, into the pasture, and then down the pasture hill, making a long frozen path about two feet wide.

On Monday recess, we took the discs, even the sharp sides were pretty dull, and sat on them, sliding down that hill on the ice path. Since we had only four base discs, everyone had to take turns. The next day some of the kids brought their sleds to school and we sledded all recess.

On Friday afternoons after recess, we had art or fun time. We did art projects or spell-downs, with everyone lining up to see who could spell the most words right and stay up the longest. Sometimes we had cipher-downs at the blackboard. Two boys in my class, Desco Lovejoy and Irving Brooks, and I would try to beat each other. Whoever got the problem right first stayed at the board until someone else beat them. Sometimes I stayed until the end, sometimes Desco or Irving.

Whenever we had to learn anything new, like the multiplication table, my dad practiced with me at home with a slate or paper and made a game of it. He and Mother had gone to their country schools, Dad in New Virginia and Mother in the Norwegian community. Mother had gone through sixth grade; Dad through the eighth or ninth.

Neither had gone to high school, and they wanted me to get a good education. Sometimes he and I would have our own spell-down. I liked school and always got the top grades in my class, making my dad proud of me. He’d say, “I wish I had four more just like you.”

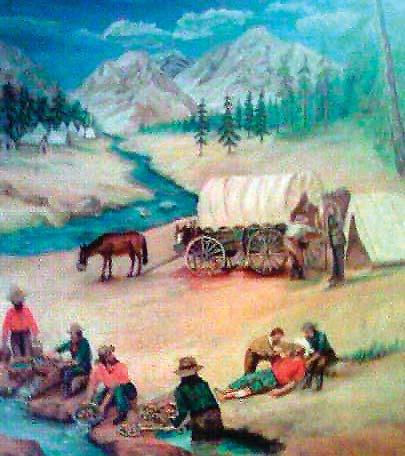

With the doll

Oil painting by Julia Marker

Chapter Nine:

Our Cather Connections

All country school students had to take county exams and pass them in order to go on to high school. You started them in seventh grade, and if you didn’t pass, you took them again in eighth. The teacher had samples to test us, then we’d go to the county courthouse in Red Cloud to take the exams, with about 80 or 100 kids from all the country schools in our county. The Webster County superintendent handed out the exams, made up entirely of essay questions, no multiple choice. Multiple choice weren’t even considered worthy of an exam back then, because that gives you the answer.

I passed all my exams in seventh grade with the second highest score in the county. The highest score belonged to Annie Pavelka, the granddaughter of Antonia, who Willa Cather had written about in her novel

My Antonia

.

That novel also had another character my family knew, the moneylender Wick Cutter. He was M.R. Bentley who held the mortgage for a time on my grandparents Hans and Sofie Walstads’ homestead.

Everyone knew the stories about that ruthless man, how he went after the Scandinavian girls so that his wife couldn’t keep any help in the house. And how he was so quick to foreclose on property if the people couldn’t pay.

As a girl, my mother always ran and hid when she saw his buggy coming down their lane. Mother said when her parents would see his fancy buggy coming, they’d all go run and hide, parents and children. If anyone was there and couldn’t pay, he was heartless, he’d foreclose. So if they were unable to pay, they’d go hide rather than face him and risk foreclosure. If Mother was there alone, she feared facing Mr. Bentley, because he would kind of sidle up to her and want to get ahold of her, pretending like he was such a nice man. He had a bad reputation among the young Scandinavian girls.