Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine (43 page)

Read Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine Online

Authors: Julie Summers

Tags: #Mountains, #Mount (China and Nepal), #Description and Travel, #Nature, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Andrew, #Mountaineering, #Mountaineers, #Great Britain, #Ecosystems & Habitats, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Irvine, #Everest

When Odell returned from Everest on 13 September 1924 he spent two days in London with Mona and his son Alasdair before leaving for Birkenhead to see Willie and Lilian. His visit was a great comfort to them and he was able to answer many of the questions they had about Sandy. He spoke to them about his final view of them climbing towards the summit and about his own search during the following days. Odell was deeply impressed by Willie and Lilian’s calm acceptance of the facts. They held no grudge and were unwilling to attribute responsibility for his death to anyone. If Odell had been at all worried on that count, for it was indeed he who had encouraged Sandy to go to Everest, he was reassured on that occasion. His loyalty to the Irvines and to Sandy’s memory has been something which the whole family has felt deeply humbled by. I cannot be sure but I would hazard a guess that Odell was the only person that Willie would ever discuss Sandy with. If anyone else attempted to draw him on the subject he would politely divert the conversation, but Odell visited him regularly until the end of Willie’s life and was always a very welcome guest in Birkenhead and later Bryn Llwyn. But his friendship did not stop there. Over the years he visited Kenneth, Alec, Evelyn, and many of my older cousins and uncles have memories of meeting Odell at one or another of the Irvine houses. The last time my father met him was at his parents’ house in the late 1950s when he joined them for dinner. Odell wrote to Bill Summers in 1986 after a letter Bill had written to the

Times

had caught his attention. He was by then in his ninety-sixth year.

Norton had offered to meet Willie on his return to England to answer any questions he might have about the expedition. The rendezvous took place in Coniston in October 1924, just before the meeting of the Alpine Club and Royal Geographical Society in London at which papers on the expedition were published. No record of this meeting exists other than the brief entry in Willie’s diary, but Norton was held in very high esteem by the whole family so I can only suppose that they had found much in common on that occasion.

Lilian had been out of the picture as the news of Sandy’s death was announced, taken up as she was with caring for and comforting the younger children. Life had to carry on for them and in August she and Willie took them on holiday to Whitby, where Willie taught Alec to row. At the beginning of October Hugh announced his engagement to Kit Paterson which provided for Lilian a very welcome diversion. She wrote a letter of congratulations in which she expressed her hope that God who had been her guide and friend all her life would protect her children. She added that when Sandy had asked for permission to go up Everest she and Willie had prayed earnestly and that thus ‘I have never had any regrets or questioning about the right or wrong of letting Sandy go up Everest – it does not stop the hole in our hearts however.’ The fact that Lilian kept out of the public eye over Sandy’s death has led people to conclude that she was unable to accept it. Great though her sadness must have been, she sought and found great strength in her belief and the main focus of her life were the other children who needed protecting and reassuring at what was a very difficult time.

On 17 October a memorial service for both men was held in St Paul’s Cathedral. The families were seated in the choir sheltered from the view of the great body of the congregation. The address given by the Bishop of Chester spoke of their courage and their achievement and of Odell’s last sighting of them so close to the top. ‘That is the last you see of them, and the question as to their reaching the summit is still unanswered; it will be solved some day. The merciless mountain gives no reply! But that last ascent, with the beautiful mystery of its great enigma, stands for more than an heroic effort to climb a mountain, even though it be the highest in the world.’ The service was attended by representatives of the King, the Prince of Wales, the Duke of York, the Duke of Connaught and Prince Arthur of Connaught in addition to the members of the expedition, the entire Mount Everest Committee, members of the Irvine and Mallory families and a great number of friends of both men. No other climbers had ever been so honoured. Willie, who was no lover of big occasions, attended the service out of duty and respect for his son, but it was for him and also for Lilian nothing like as personal an occasion as the service taken by Mallory’s father in Birkenhead in June.

After the service there was a joint meeting of the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club at the Royal Albert Hall where reports from the expedition were presented by General Bruce, Norton, Geoffrey Bruce and Odell. The talks were illustrated with slides from the expedition and it was here, for the first time, that Willie and Lilian saw photographs of Sandy in Tibet. This was a great moment for them all when they really had a chance to understand what life had been like for him over the last few months before his death. Lilian was particularly impressed by the photograph of the rope ladder taken by Somervell and asked Willie to arrange for a copy to be given to the family.

One person from the Mount Everest world who turned out to be extraordinarily kind and sympathetic, rather against expectation from what else I have ever read of him, was Arthur Hinks. He was in constant touch with Willie from June onwards and made every attempt to communicate any new information received as quickly as possible. He also ensured that copies of all the official letters and telegrams were forwarded to Birkenhead and as soon as Sandy’s personal effects arrived in England he arranged for them to be sent straight to the family. Hinks was instrumental in getting for the family as many photographs of Sandy as were known to exist and it was he who fulfilled Lilian’s request for a picture of the rope ladder Sandy had made. Hinks saw that copies were sent to her and an enlargement of it hung in the study at Bryn Llwyn until Willie’s death. Hinks was also concerned to retrieve the disassembled 1922 oxygen apparatus that Sandy had taken from the RGS in November 1923. In an amusing exchange of letters he and Willie discussed whether the bits and pieces that were returned actually constituted a whole apparatus, so completely had Sandy dismantled it. In the summer of 1925 Hinks wrote again to Willie enclosing a copy of the photograph taken by Odell of Sandy and Mallory leaving Camp IV that had only then come to light.

Over the next months and years memorials to the two men sprang up all over the country. Sandy was commemorated at Merton College by a sculpture of an eternal flame on a plinth with the lettering carved by the artist Eric Gill and at Shrewsbury by a relief plaque on the chapel wall. Birkenhead named two new streets after their famous sons and a joint memorial window was unveiled in early 1925 in the cloisters of Chester Cathedral. It depicts St Bernard with his dog standing in front of a huge mountain with the inscription below: ‘To remember two valiant men of Cheshire. George Leigh-Mallory and Andrew Comyn Irvine who among the snows of Mount Everest adventured their lives even unto death. “Ascensiones incorde suo disposuit” Ps LXXXIV’. It was the family’s local memorial and every anniversary of Sandy and Mallory’s death Willie would drive to Chester, often with Lilian, to place flowers beneath the window. Lilian once told Hugh that they were very conscientious and would return a few days later to remove the flowers.

After the memorial service and meeting in London the family returned to Birkenhead, the only outstanding arrangement being the sorting through of Sandy’s possessions and his will. Hugh took responsibility for the legal matters, as Sandy’s executor, and settled all the accounts which were still to be paid. He and Willie went through the suitcases that Odell had packed at Base Camp and sorted what should be kept. Sandy’s spare ice axe turned up in the post a few weeks after the suitcases had arrived. It simply bore the label ‘Irvine: Birkenhead’ in Odell’s neat handwriting. This axe was the one Bill Summers saw hanging in the gun room at Bryn Llwyn twenty-five years later. The label was preserved in an envelope along with all the other papers that had come back from Everest. I suspect Willie threw nothing away.

The years after Sandy’s death were busy ones for the family. Willie retired from business in 1926, shortly before his father died aged 91, and he and Lilian moved from Birkenhead to Bryn Llwyn in 1927. Evelyn married Dick Summers in 1925 and Hugh Kit Paterson in 1926. Then followed grandchildren which kept Lilian both happy and fulfilled. All the five children led full and active lives. Hugh became senior partner in the law firm, Slater Heelis in Manchester; Kenneth qualified as a GP and lived and worked all his life in Henley. He became a member of the Alpine Club and was always a keen climber and regular visitor to the Pen-y-Gwryd hotel in Snowdonia. Alec spent a part of his working life in India and moved to Bryn Llwyn in the 1970s. He continued to keep in touch with Odell and was the member of the family who was most keen to pass on his memories of Sandy to his children. Tur lived at Bryn Llwyn until he married. Like the others he studied at Magdalen College after which he went into the Church, becoming the Dean of St Andrew’s, Dunkeld and Dunblane in 1959, an office he held until he retired in 1983.

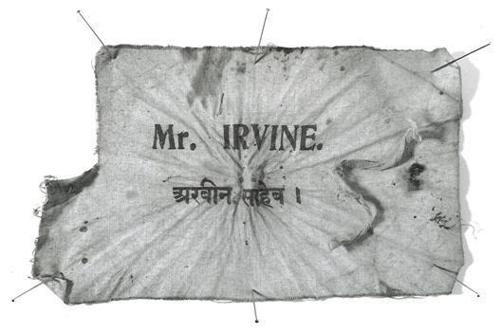

In 1931 Evelyn received a small package from India. It came from George Wood Johnson, a prominent member of the International Kangchenjunga expedition and had been given to him by Lobsang, one of Sandy’s porters in 1924. In the package was a small piece of material bearing Sandy’s name in English and Nepali which had wrapped in it twenty tiny Himalayan garnets. Willie wrote to Odell about the package who replied ‘I was interested to hear about the garnets, but cannot understand how they were “recovered” on Kangchenjunga by Lobsang! I think myself it must be that Lobsang made a little collection of these stones in the Kangchenjunga neighbourhood as a present & a recollection of Sandy.’ Evelyn kept the garnets safely tied up in the piece of material and when she died my father found them amongst her most personal possessions.

The scrap of material which had contained the garnets

The scrap of material which had contained the garnets

In 1925 the official expedition book appeared entitled

The Fight For Everest: 1924

. It is a wonderful and vivid account of the whole expedition from the outset to the trek back to Darjeeling. All the expedition members contributed to the book and in Norton’s piece, which considers the characters of the two climbers who died, he wrote of Sandy:

Young Irvine was almost a boy in years; but mentally and physically he was a man full grown and able to hold his own with all modesty on terms with the other members of our party, who averaged twelve years older than he. One more invaluable characteristic was his turn for things mechanical, for in this respect he was nothing short of a genius, and he became our stand-by in dealing with the troubles and difficulties we encountered over this year’s oxygen apparatus, and, for the matter of that, in every department – from a lampshade to a rope ladder.

He shares with Odell the credit of having show us all how to ‘play for the side’, stifling all selfish considerations, for nothing in the record of 1924 was finer than the work these two put in as ‘supporters’ at Camp IV.

Sandy Irvine’s cheerful camaraderie, his unselfishness and high courage made him loved, not only by all of us, but also by the porters, not a word of whose language could he speak. After the tragedy I remember discussing his character with Geoffrey Bruce with a view to writing some appreciation of it to The Times; at the end Bruce said: ‘It was worth dying on the mountain to leave a reputation like that.’ Men have had worse epitaphs.

Sandy and Mallory became legendary figures. Their final hours were minutely scrutinized by the press and public alike, and whenever anything to do with climbing Everest was written, their names appeared and accounts of their climb were published.

Great debate raged over the ‘last sighting’ by Odell who, over the course of the following years, changed his story in the light of so much interest and informed opinion. His initial diary entry states that he saw the two men ‘at the foot of the final pyramid’. This was altered by the time he arrived at Base Camp and in his dispatch to the

Times

he wrote the now renowned paragraph in which he described the tiny black spots silhouetted against the snowcrest beneath a rock-step in the ridge. A few months later he had changed his story again. Scrutiny of his sighting and subsequent analysis convinced him, it would appear, to rethink. In his account in the

Fight for Everest: 1924

he wrote, ‘I noticed far way on a snow slope leading up to what seemed to me to be the last step but one from the final pyramid, a tiny object moving and approaching the rock step. A second object followed, and then the first climbed to the top of the step. As I stood intently watching this dramatic appearance, the scene became enveloped in cloud once more, and I could not actually be certain that I saw the second figure join the first.’