Films of Fury: The Kung Fu Movie Book (32 page)

Read Films of Fury: The Kung Fu Movie Book Online

Authors: Ric Meyers

And speaking of the world, that was John Woo

’s oyster when he left Asia. He was renowned as the greatest action filmmaker ever, with fans in every pocket of the globe. He was declared an artist and auteur … even a genius. It seemed that nothing could stop him. What could possibly go wrong?

Read on ….

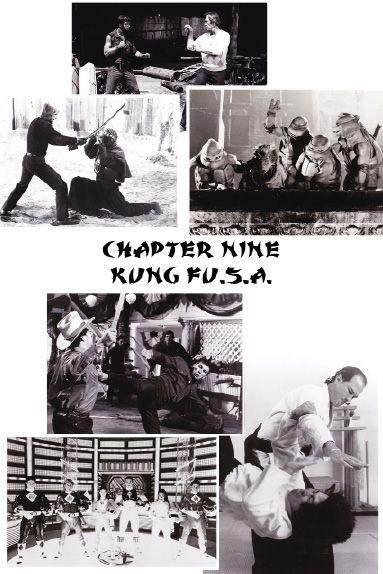

Picture identifications (clockwise from upper left):

Chuck Norris

vs. Tadashi Yamashita in

The Octagon

; Chuck Norris

vs. David Carradine

in

Lone Wolf McQuade

; Teenage Mutant Ninja

Turtles and Shredder; Steven Seagal

; Tom Laughlin

in

Billy Jack

; Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers.

Let’s face it. The American film industry doesn’t like kung fu. On

e reason is that the American audience who loves it is not the same as the American audience that loves chop-socky. There’s some overlap, sure, but mostly the ones who love true kung fu films are the ones who love musicals. Real kung fu films combine the emotions of opera with the movement of dance, even ballet.

This reality is totally lost on the producers who fashion and market their chop-socky to the urban audience. If they honestly looked at which American kung fu films succeeded beyond their wildest expectations, it was the ones that were fashioned and promoted to the

family

audience.

Rush Hour

,

Kung Fu Panda

(2008), The 2010 “

Karate

”

Kid

. Even

Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon

.

The bulk of the American film industry denies this — relegating those films, and others, to the category of “exceptions.” Or they take the likes of

Hero

, and, especially,

Shaolin Soccer

(2001), and package them as urban audience films, which they are, quite patently, not. It would be as if distributors had taken

Lawrence of Arabia

(1962) and

Blazing Saddles

(1974), stuck samurai swords in the characters’ hands on the DVD covers, dressed them in t-shirts, swathed the foreign backgrounds in manila paper, and sold them as exploitation flicks. That is, if they released them at all.

Whether this is simply blinkered ignorance or standard operating racism, is for you to decide. What’s quantifiable is that Hollywood is much more comfortable with Japanese martial arts: karate

, aikido

, judo

, kick-boxing

, even ninjitsu

— the kind of straight-limbed, muscle-and-anger-driven fighting that has been tinseltown’s stock-in-trade since the advent of the motion-picture camera.

In order to make the action clear in the earliest days of cinema, directors favored exaggerated, wide, movements like the classic round-house punch. This long, elaborate, telegraphed move found favor amongst producers and was cemented in the 1940s, when long fight scenes became common-place in Westerns and cliffhanger serials. There, subtlety was to be avoided at, literally, all costs. After all, training actors and filming elaborate fights took time, and time was money.

“In Hong Kong,” Jet Li

said, “a greater proportion of the audience are used to fight scenes that last five to ten minutes with unusual, esoteric wushu movements. But I think Americans may be more used to boxing — with all its straight strikes — that last maybe thirty seconds before someone falls down. But there really wasn’t more time to do the martial arts in America than there was in Hong Kong. You see, in Hong Kong, if the shooting schedule is for three months, we work on the kung fu scenes for maybe two months, and the drama for one. In American films, maybe two months on the drama, one month on the fighting. So we still don’t have enough time.”

Studios may not have the time, but, in truth, they really don’t have the inclination either. Because

Enter the Dragon

producer Fred Weintraub

was right when he said that Americans think of kung fu as fantasy. First, it has been sold to them as a martial art, not as self-improvement, and second, what’s the point of having a system that takes years to master when you can just pick up a gun? U.S. history is not about “excellence of self.” It’s about “excellence of

aim.

”

To put it bluntly, Americans have never been without the gun, and a majority of chop-socky filmgoers really can’t understand why two people would engage in a dance of death with limbs or swords when a bullet could resolve matters much more easily.

Ironically, as more Asian kung fu films are bought for distribution in the English-speaking world, standard operating ignorance has come back to haunt the translators. Some of the best kung fu in John Woo

’s

Red Cliff

was edited out of the American version for being too unrealistic, when it most patently wasn’t. It was merely unusual to American editors’ eyes, who were accustomed to chi-wasting round-house punches. One of the best jokes in

Ip Man

(2008) was ruined by translators who didn’t comprehend the kind of kung fu the hero was doing (changing “if you don’t start fighting” to “if you start fighting” because they couldn’t distinguish between defensive and offensive kung fu).

That originally started to change with the coming of Bruce Lee

. Prior to him, martial arts in American movies were relegated to glimpses of exotic, esoteric fighting skills they called “judo

” in

Blood on the Sun

(1945) starring Jimmy Cagney

and

The Manchurian Candidate

(1962) starring Frank Sinatra

. An argument can be made (and I often do) that the first real kung fu fight scene in English-speaking cinema was the train battle between Sean Connery

and Robert Shaw

in the second James Bond

film,

From Russia with Love

(1963). There the characters only move as much as they have to, and shun round-house punches in favor of direct, effective techniques. They also involve their cramped environment Jackie Chan

-style … as much as two hulking, muscle-bound Englishmen can.

Also in there kicking was Tom Laughlin

. Born in 1938, Laughlin became an actor in the 1950s, and was featured in several major Hollywood productions, including

Tea and Sympathy

(1956),

South Pacific

(1958), and the original

Gidget

(1959). His destiny, however, was in the exploitation genre. Giving up the tinseltown rat race, he decided to write, direct, produce, edit, and star in

The Young Sinner

(1965), establishing his ongoing theme of misunderstood youth. Two years later he hit the mother lode with

The Born Losers

(1967), which introduced his character of a heroic, laconic, karate

-trained half-breed named Billy Jack

.

The Born Losers

made more than ten million dollars — an extraordinary amount of money for a mere exploitation film. He spent the next four years making, and then distributing, the movie he is most remembered for:

Billy Jack

(1971).

This story of an ex-Green Beret who fights rednecks and a corrupt sheriff’s office to protect a Freedom School for hippie runaways (located on an Indian reservation, yet!) featured real-life martial arts expert Bong Soo Han

. The movie cost eight hundred thousand dollars to make, and made more than eighteen million. Laughlin followed that with heart-felt, but increasingly less effective, sequels, as well as

The Master Gunfighter

(1975) — his portentous remake of Hideo Gosha

’s great Japanese epic

Goyokin

(1969), transposed to the American West.

But, by then,

Enter the Dragon

had appeared. The Chinese kung fu cat was out of the bag, as it were, and once seen, could not be forgotten … but damned if Hollywood could figure out a way to exploit it. To their credit, producer Weintraub and director Robert Clouse

tried to recapture lightning in a bottle. To their debit, they didn’t do a very good job. Their big mistake: avoiding kung fu like the plague. In 1974, they featured

Enter

co-star Jim Kelly

as

Black Belt Jones

(1974) — a fondly remembered blaxploitation effort with a serious credibility problem. Why would the white mob be so intent on taking over a martial arts school in the middle of Watts anyway?

Next the duo tried

Golden Needles

(1974).

Brilliantly (sarcasm), they replaced the lithe Lee with the burly Joe Don Baker

, who starred as a brutish mercenary out to find a fabled Asian statue that held the promise of eternal youth. When that didn’t work in any way, Weintraub and Clouse finally decided to return to the source. If they had found a kung fu talent like Lee in Hong Kong before, maybe they could do it again. And here my memory runs into trouble.

After my formal interview with Fred Weintraub

more than twenty-five years ago, I brought up the remarkable similarity between Yul Brynner

in

The Ultimate Warrior

(1975) and Gordon Liu

Chia-hui

in

The

36

th

Chamber of Shaolin

, which appeared two years later. At the time of

The Ultimate Warrior

’s production, Liu was making the transition from a supporting actor and stuntman on Chang Cheh

’s films to Huang Fei-hong in Liu Chia-liang

’s

Challenge

of the Masters

(1976). My contention was that if Gordon had starred in Weintraub and Clouse’s post-apocalyptic action drama, they might have made America’s second great kung fu discovery.

To the best of my recollection, Weintraub alluded to the fact that he had, indeed, scoured Hong Kong for a new star; that Gordon, although young, showed great promise; and, if not for Liu’s Shaw Brothers

contract and/or the American studio’s desire for an established box office name,

The Ultimate Warrior

would have been a showcase for Liu Chia family fist the way

Enter the Dragon

was a showcase for jeet kune do

. As it was, the well-intentioned, fight-filled film collapsed under the weight of its mediocre choreography and screenplay. Following that fiasco, Weintraub reteamed with Jim Kelly

for

Hot Potato

(1976) — a dreadfully titled, painfully mediocre film with the actor demoted to playing one of three mercenaries hired to rescue a senator’s daughter held captive in Thailand

.

When that flick also died at the box office, Weintraub and Clouse decided to shoot the works. Taking the plots from

Enter the Dragon

and

Hot Potato

,

they hired three of America’s best real-life martial artists, then threw in a burly black, a beautiful blonde, and a heinous Asian villain. They called it

Force Five

(1981), and it was not good. Their hearts were in the right place, but their filmmaking skills were not. This painful waste squanders the abilities of World Heavyweight Karate Champion Joe Lewis

, World Kickboxing Champion Benny “the Jet” Urquidez

(who looked great fighting Jackie in

Wheels on Meals

and

Dragons Forever

), and Richard Norton

(who looked great fighting Sammo in

Twinkle Twinkle Lucky Stars

and Jackie in

City Hunter

), not to mention Bong Soo Han

, who played Reverend Rhee(!), an evil minister who lived on an island with his own “Maze of Death.”

Sound familiar? Despite its obvious origins, had the script been half as clever and the fights half as good as in

Enter the Dragon

,

the movie might have had a chance. It wasn’t, they weren’t, and it didn’t. Weintraub and Clouse never gave up, bless them. They tried Jackie Chan

in

The Big Brawl

and Cynthia Rothrock

in the

China O’Brian

series (1990-1991), but the two stars, unlike Bruce, would not force superior kung fu on them. It seemed that without Lee, Weintraub, Clouse, and the American kung fu movie was in a maze of death without a map.

Things seemed about to change with the publication of

The Ninja

(1980), Eric von Lustbader’s evocative espionage novel which introduced mainstream fiction readers to the ancient sects of Japanese assassin-spies thirteen years after 007 had showcased them in

You Only Live Twice

(1967). It took Lustbader’s novel to inspire Richard Zanuck

and David Brown

, producers of

Jaws

(1975),

to mount a multi-million-dollar, grade-A adaptation. And if that happened, maybe top producers would smile on Chinese kung fu as well. But it was not to be.