Financial Markets Operations Management (3 page)

Read Financial Markets Operations Management Online

Authors: Keith Dickinson

I have been involved in Operations for over forty years as a practitioner, an executive education trainer and university lecturer. In my practitioner days, there was very little by way of reference books that addressed Operations; in addition, the Internet had yet to enter our collective consciousness. As a consequence, it was difficult for those working in Operations to find any literature that dealt with their topic.

Today, we can research any topic we choose, including Operations, by accessing the Internet, clicking through websites managed by exchanges, depositories, custodians, regulators and various trade associations. In spite of this, and with one or two notable exceptions, there is a dearth of books that enable Operations professionals to navigate the settlement and post-settlement environment for securities and derivatives.

This book,

Financial Markets Operations Management

, fills that information gap.

The intended audience is fourfold. Firstly, the text may be used in a teaching context as a course reader for staff already working in an operational environment. Secondly, as a reference guide for students taking a financially focused first degree or Masters course. Thirdly, for staff working in non-operational areas that are interested in what happens “after the trade has been executed”. Finally, for those who are about to enter the financial world or who simply have a passing interest in the subject, this book is for those readers.

The text covers the trade lifecycle for securities and derivatives products from trade capture, pre-settlement and settlement through to the custody of assets and asset servicing. It is divided into four parts, as follows:

- Part One: An understanding of operations in the context of financial instruments, data management and the different types of organisation.

- Part Two: The post-trade processing of financial instruments; trade capture, clearing and settlement.

- Part Three: The post-settlement environment of safekeeping, asset servicing and asset optimisation.

- Part Four: A consideration of two key controls â accounting for securities and asset reconciliation.

Chapters are broken down as follows:

- Chapter 1 looks at the organisational structure of a typical investment company and at the Operations Department in particular. We consider the internal and external relationships that Operations manage.

- Chapter 2 defines the main financial instruments, explains the operational features and shows the transaction calculations including accrued interest for bonds.

- Chapter 3 considers the importance of data and its management.

- Chapter 4 explains how the various intermediaries and market infrastructures enable lenders and borrowers to operate.

- Chapter 5 starts the post-trade processing phase by looking at the clearing systems and distinguishing between clearing houses and central counterparties.

- Chapter 6 continues looking at the infrastructure and in particular the securities depositories.

- Chapter 7 follows the initial post-trade processes of clearing and the pre-settlement forecasting of cash and securities.

- Chapter 8 describes the different types of settlement including “delivery versus payment”, the reasons why trades fail to settle and what actions can be taken to manage the fails.

- Chapter 9 changes focus from securities to derivatives with a look at how exchange-traded and over-the-counter derivative products are cleared.

- Chapter 10 looks at the safekeeping of securities including the use of nominee names and the relationships between the beneficial owner and the securities issuer, together with the intermediaries such as custodians and securities depositories.

- Chapter 11 introduces the reader to what is considered to be the most risky area within Operations â corporate actions. This chapter looks at the complexities, processing requirements and information flows of this topic.

- Chapter 12 describes the different forms of securities financing and includes user motivations and the lifecycle. Securities financing is not risk-free; this chapter addresses the risks and the ways in which these risks are mitigated.

- Chapter 13 looks at the impact of securities transactions on the Profit & Loss Statement and Balance Sheet together with the transaction lifecycle from an accounting perspective.

- Chapter 14 explains the importance of efficient and timely asset reconciliation and how it might be used as a predictive tool to prevent problems from occurring.

To cover the entire operational spectrum would require a text containing many hundreds, if not thousands, of pages. In order to overcome this problem I have concentrated on what I consider to be the main operational processes for securities and derivatives. Whilst I do not cover every type of equity, bond and derivative, there is sufficient detail to enable the reader to understand what happens in the engine room of the financial

markets, i.e. after the trade is executed.

Therefore, I have not included regulation other than by occasional reference. We are subjected to regulation for a variety of reasons â for example, to maintain confidence in the financial

system â and it is both complex and technical. Furthermore, in a global context, there are different and sometimes conflicting regulations from country to country.

I have also excluded commodities for two reasons. Firstly because in the physical world, types of commodities behave in different ways â think of the processes that enable you to pump petrol/gas into your car or electricity to light up your home. By contrast, commodities derivatives are cleared in similar ways to financial derivatives. Secondly, there is already an excellent book written by a friend and colleague, Neil Schofield.

1

Finally, this book does not cover funds administration. This relates to activities that support the running of a collective investment scheme (for example, a traditional mutual fund, hedge fund, pension fund, unit trust or similar variation).

In any event, there is more than enough material within the regulatory, commodities and funds administration world for an additional three books.

Students and instructors can find additional resources at

www.wiley.com

.

Thanks to John Evans, FMT, who suggested the idea of writing the book, and to Colin Hill, Shelby Limited, who reviewed the first draft of the manuscript. At Wiley, I'd like to acknowledge the work of Development Editor Meg Freeborn, Acquisitions Editor Thomas Hyrkiel, Assistant Editor Jennie

Kitchin, Senior Production Editor Tessa Allen and Copy-Editor Helen Heyes.

Introduction to Operations

For every action there is a reaction. For every transaction, there has to be an appropriate sequence of processes such as a payment, a delivery of an asset, an exchange of information or a combination of these. We refer to this as an

operational process

. In this introductory chapter, we will see how an investment company's Operations Department relates to other departments within the company and other external organisations.

Firstly, we need to distinguish the operations of an organisational entity and the entity's post-transactional operations.

What do the following types of business actually do?

- Vineyard?

- Publisher?

- Hotel?

- Insurance company?

In simple terms, these businesses produce something (often referred to as

outputs

):

- Vineyards produce wine;

- Publishers produce books, newspapers and computer software;

- Hotels produce satisfied customers;

- Insurance companies help customers reduce their financial risks.

These outputs are the results of the transformation of a variety of

inputs

, including some of the following (the list is not exhaustive):

- Vineyard â grapes, yeast, water, sugar, etc.

- Publisher â authors, ideas, paper, digital resources, etc.

- Hotel â premises (rooms, dining areas), food, staff (front of house, catering, cleaning), ambiance, etc.

- Insurance company â products, sales staff, research & development staff, distribution channels, etc.

This is what businesses “do”; we know this as the business operations and the transformation of inputs into outputs are how each business operates.

What is missing here is the processing that occurs after the inputs have taken place. A trader executes a transaction; the decision-making that led to the requirement to transact, the negotiation with a counterparty and the final execution of the transaction are all part of the business operation. What happens next is the completion of that deal. By completion, we mean the settlement, the exchange of the financial instrument for cash. This processing, this completion, is what financial market operations is all about. It is what we in the Operations Department do.

There is, therefore, a distinction between the operations of a business and Operations in the sense of processing most of the inputs. In this opening chapter you will learn:

- How an investment company is typically structured;

- What the departments' roles are;

- What relationships Operations have with internal departments and external entities;

- Other service functions within the business.

There is no right or wrong way to organise the structure of an investment company. It depends on the size of the company, the products in which it deals and the locations of its offices.

The biggest companies, for example the investment banks, will have several thousand staff located in offices based around the world. By contrast, the smallest, such as a hedge fund, might have less than 100 staff working from one office.

What is usually certain is that there will be one department that generates business for the company and one that ensures that the business is administered in an efficient, controlled, timely and risk-free manner. In many companies there will be a third department that supports these two.

We refer to these three departments or offices as follows:

- Front Office â the business generator;

- Middle Office â the administrator;

- Back Office

1

â the supporter.

The Front Office generates revenue and is responsible for the buying and selling of financial products.

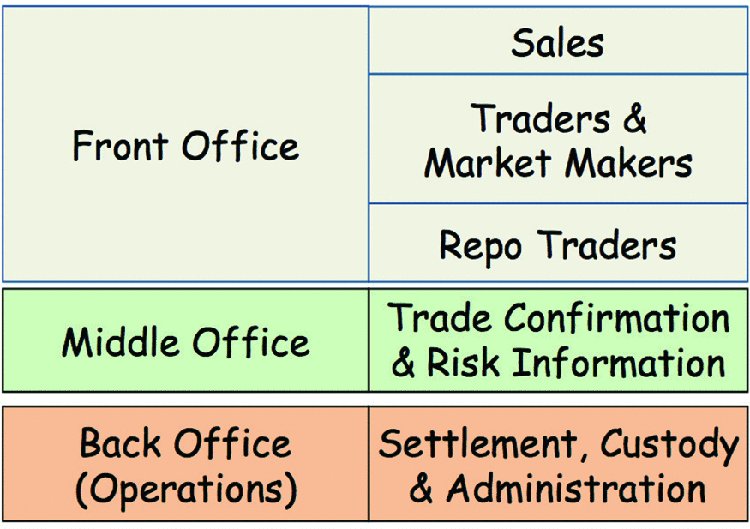

Within the Front Office (see

Figure 1.1

) there are generally five areas:

- Corporate Finance

â This area helps clients to raise funds in the capital markets and advises clients on mergers and acquisitions. Corporate finance can be divided into industry coverage (e.g. financial institutions, industrials, healthcare, etc.) and product coverage (e.g. leveraged finance, equity, public finance, etc.). - Sales

â The sales desk will suggest trading ideas to clients (institutional and high- net-worth individuals) and take orders. Orders must be executed at the best possible price and this can mean placing an order internally or with an external trading desk. - Trading

â The trading desk (aka the dealing desk) executes trades on behalf of the investment organisation (known as principal, proprietary or own-account trading). The traders can take both long and short positions in financial instruments that they have been

authorised to trade in. This desk also executes trades on behalf of the sales desk, as noted above. - Repo Desk

â The repo desk supports the traders by helping to finance their positions. When the traders go long, they need to borrow cash. The repo traders borrow cash through repo. Conversely, when the traders go short, they need to borrow securities. The repo traders borrow securities through reverse repo. - Research

â Research is undertaken for a variety of reasons. For example, equity research review companies write reports about their prospects and make “buy”, “sell” or “hold” recommendations. Predominantly, research is a key service in terms of advice and strategy; it covers credit research and fixed-income research amongst others.

FIGURE 1.1

Investment organisation â structure

There are other, similar types of Front Office used by organisations, such as:

- Stockbrokers

â These act in an agency capacity on behalf of clients. They can offer “execution only” (without any advice) brokerage, non-discretionary services (provide advice but can only trade subject to a client's instructions) and fully discretionary services (the broker decides what to do based on the client's overall investment objectives without seeking case-by-case instructions). - Market makers

â These make their money by using their company's capital to quote bid and offer (buy and sell) prices in pre-specified securities. Market makers are obliged to make a two-way price in any and all market conditions. - Investment managers

â These use their clients' cash to make investment decisions in accordance with the clients' investment objectives. Having made the investment decisions, orders are placed with their brokers for execution in the market. - Broker/Dealers

â These can act as both a dealer (trading for the organisation's own account) and as a broker (on behalf of clients). - Inter-dealer brokers

â These are specialised intermediaries that execute transactions on behalf of sell-side institutions such as broker/dealers and market makers. The IDBs provide anonymity so that the market is not aware of the sell-side institution's positions.

In whatever capacity it is acting, the Front Office executes transactions either on a stock exchange or in the over-the-counter (OTC) markets.

Not every investment company is obliged to have a Middle Office, but the larger the company, the more likely it is to have one. The Middle Office is the link between the Front Office and the various operational departments (see

Figure 1.2

).

FIGURE 1.2

Investment organisation â structure

It both supports and controls output from the Front Office; it ensures that any trade is correctly booked and the economic consequences of the trade comply with various pre-agreed limits, for example:

- The value of the trade must be within counterparty limits;

- The value of the trade must be within the trader's limits;

- The trader must be authorised to trade that asset.

The Middle Office monitors existing trades and identifies any that do not meet these limits. Assets held in the dealers' blotters should be checked and revalued daily. The Middle Office needs to ensure that pricing data are correct and investigate prices that do not look right.

The Middle Office will exchange confirmations of executed trades with the counterparties and, where necessary, identify discrepancies, obtain the dealer's confirmation of the change and update the trading systems accordingly. Changes cannot be made without reference back to the trading floor, as it could appear that the Middle Office is actually trading rather than simply making a correction to a trade.

As part of the monitoring process, the Middle Office ensures that all the trades executed during one particular day are fully booked in the system, that valuations have been made and that reports have been produced.

In most cases where there are discrepancies in transaction details, the Middle Office would have to investigate with the Front Office. In

Table 1.2

there is a list of typical types of query together with the department that is responsible for making any changes.

TABLE 1.2

Primary responsibilities for resolving trade discrepancies

| Settlement Instruction Component | Trade Detail from which Settlement Instruction Component is Derived | Primary Responsibility |

| Depot account no. | Trading company | Front Office and/or Operations |

| Nostro account no. | Trading company | Front Office and/or Operations |

| Trade reference | N/A | N/A |

| Deliver/Receive | Purchase or Sale | Front Office |

| Settlement basis | DVP or RVP or FoP | Front Office |

| Settlement date | Settlement date | Front Office |

| Quantity | Quantity | Front Office |

| Security reference | Security | Front Office |

| Settlement currency | Settlement currency | Front Office |

| Total net amount (Principal) | Price | Front Office |

| Total net amount (accrued interest) | Accrued interest | Operations |

| Counterparty's depot account | Counterparty (Cpty) | Cpty = Front Office Cpty account = Operations |

| Counterparty's nostro account | Counterparty (Cpty) | Cpty = Front Office Cpty account = Operations |

For those organisations that do not have a Middle Office, the initial trade capture from the dealing systems would start here in the Operations area (see

Figure 1.3

). It is here that all the post-trade processing takes place, and this includes activities such as settlement of all transactions. Settlement requires the receipt and delivery of securities together with the payment and receipt of cash; as we will see later, we expect the movements of securities to occur at the same time as the corresponding movements of cash. We refer to this as

delivery versus payment

or

receipt versus payment

(DVP and RVP, respectively).

FIGURE 1.3

Investment organisation â structure

More often than not, securities held centrally in a type of organisation known as a central securities depository (CSD) are recorded as electronic records by the CSD. For this reason,

Operations will also have responsibility for ensuring that when transactions settle, the correct amount of securities is either credited (for purchase) or debited (for a sale) at the relevant CSD.

Operations may or may not be a direct participant within a CSD; if not, Operations will make use of an organisation such as a custodian bank that does have direct participation with the CSD. So we now have a custody or safekeeping responsibility in addition to settlements.

As we will see throughout this book, many of the operational responsibilities refer to the processing and final completion of transactions that have come out of the Front Office. There are other aspects to consider as well:

- Monitoring and control â Operations must make sure that any payments and deliveries are made with the appropriate level of authorisation. Authorisation can include a tested telex, an authenticated email, an authenticated fax, a signed (and possibly countersigned) hardcopy instruction or a message delivered through a secure and automated electronic messaging system such as SWIFT.

- Reconciliation â This is a key control designed to ensure that the organisation can verify that assets recorded in the books and records of the organisation agree with external statements received from counterparties, banks, custodians, etc.

- Protection of revenues â Revenues are generated in the Front Office and there will be certain, known costs that each transaction will be subject to. Examples of these costs can include brokerage fees, transaction fees, custody charges, clearing fees and stamp duty.

These represent the cost of doing business; however, if there are processing errors, there is every likelihood that there will be penalty costs associated with this. In a perfectly efficient environment where no mistakes are made, there should be no need for any penalty costs to be incurred. If, for example, a payment is made late, then it is quite possible for the interest charge to be greater than the profit made on the underlying transaction. Operations staff members have to pay great attention to detail in their attempts to avoid problems such as these.