Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (12 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

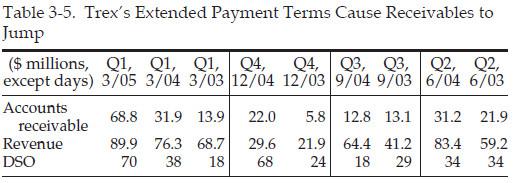

Several months later, Trex predictably announced that its revenue for June 2005 would be much lower than Wall Street expectations. Trex’s sharp increase in receivables (see Table 3-5), together with the company’s disclosure of extended payment terms and an early buy program, should have alerted investors to the coming slowdown in sales growth.

Concluding Thoughts and Commentary

This chapter focused on attempts to shift future-period revenue to an earlier period. Two additional pertinent issues require some clarification at this point:

(1)

what will be the impact on future periods’ revenue, and

(2)

what happens if management gets caught using this shenanigan?

Impact on Future Periods’ Revenue

When management employs Shenanigan No. 1, it clearly has concluded that the current period takes precedence over a later one, as it is depleting revenue from the later period and adding it to an earlier one. Had management properly posted a credit to the reserve account with services still to be provided, that credit reserve would be released as revenue in future periods.

Impact of Management’s Getting Caught Cheating and Correcting Financial Reports

One of the ironies that is little known to investors’ concerns the financial reporting benefit that management receives when it restates results caused by premature revenue recognition.

A Gift That Keeps Giving—The Result of Accounting Restatements

Companies that are found to be recognizing revenue prematurely must restate the beginning retained earnings on the Balance Sheet. Think of the retained earnings as the repository of all previously recorded profits. Thus, any previously recognized revenue would have been transferred to this account from the Statement of Income.

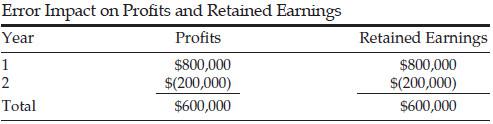

Consider a software company that sells a five-year licensing deal for $1,000,000, receiving $200,000 up front and the remainder ratably over the contract term. Assume that the company records the entire $1,000,000 as revenue during the first year and defers nothing. Also assume that this error was not found until the beginning of year 3, at which time the auditors require an accounting restatement resulting from premature revenue recognition of $600,000 (the difference between the $1,000,000 recognized and the correct $400,000 total for the first two years). Let’s now analyze the impact of the premature revenue recognition on profits.

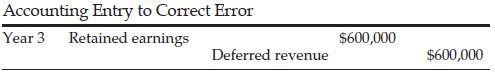

Since the profit accounts for each year would have been transferred to retained earnings, the correcting entry would remove the inflated $600,000 profit from retained earnings and establish a deferred revenue account.

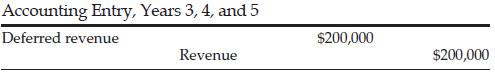

Now that the error has been corrected for the premature revenue recognized for years 1 and 2, the company is now ready to record the correct $200,000 revenue for years 3 through 5.

Who Says Crime Does Not Pay?

Had the company played by the rules, it would have recorded revenue totaling $1,000,000 ratably over the five years. In using Shenanigan No. 1 and prematurely recognizing the $1,000,000 at the outset, then restating for the error, the company

actually reported to investors

$1,600,000 over the five years (reversal of past years’ revenue is often ignored by Wall Street, particularly if it can be recognized again). And they say crime does not pay!

Well, in the short term, companies might indeed receive an unfair gift from the restatement and a “second helping” of revenue. However, prudent investors know that management’s use of any accounting shenanigans should be viewed in a negative light and should avoid owning companies with suspect financial reporting practices.

Looking Back

Warning Signs: Recording Revenue Too Soon

• Recording revenue before completing any obligations under the contract

• Recording revenue far in excess of work completed on a contract

• Up-front revenue recognition on long-term contracts

• Use of aggressive assumptions on long-term leases or percentage-of-completion accounting

• Recording revenue before the buyer’s final acceptance of the product

• Recording revenue when the buyer’s payment remains uncertain or unnecessary

• Cash flow from operations lagging behind net income

• Receivables (especially long-term and unbilled) growing faster than sales

• Accelerating sales by changing the revenue recognition policy

• Using an appropriate accounting method for an unintended purpose

• Inappropriate use of mark-to-market or bill-and-hold accounting

• Changes in revenue recognition assumptions or liberalizing customer collection terms

• Seller offering extremely generous extended payment terms

Looking Ahead

Chapter 3 outlined the following four techniques used to recognize revenue prematurely:

(1)

recording revenue before completing any obligations under the contract

(2)

recording revenue far in excess of the work completed on the contract

(3)

recording revenue before the buyer’s final acceptance of the product

(4)

recording revenue when the buyer’s payment remains uncertain or unnecessary

While Chapter 3 addressed tricks involving mainly legitimate sources of revenue (albeit reported in an incorrect period), Chapter 4 moves to an arguably more audacious revenue recognition transgression: recording bogus or fictitious revenue.

4 – Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 2: Recording Bogus Revenue

The previous chapter discussed situations in which companies record revenue too soon. While this is clearly inappropriate, the acceleration of legitimate revenue is less audacious than simply making the revenue up out of thin air. This chapter describes four techniques that companies employ to create bogus revenue and some warning signs for investors to spot this nefarious shenanigan.

Techniques to Record Bogus Revenue

1. Recording Revenue from Transactions That Lack Economic Substance

2. Recording Revenue from Transactions That Lack a Reasonable Arm’s-Length Process

3. Recording Revenue on Receipts from Non-Revenue-Producing Transactions

4. Recording Revenue from Appropriate Transactions, but at Inflated Amounts

1. Recording Revenue from Transactions That Lack Economic Substance

Our first technique involves simply dreaming up a scheme that has the “look and feel” of a legitimate sale, yet in reality lacks economic substance. In these transactions, the so-called customer is under no obligation to keep or pay for the product, or nothing of substance really was transferred in the first place.

In his brilliant 1971 hit song, John Lennon challenged us to “imagine” a perfect world. Imagination has undoubtedly helped the world become a better place, as people’s creativity has broken boundaries and led to countless innovations. Imagination has inspired talented scientists, for example, to diagnose the unknown and find cures for diseases. Similarly, technological entrepreneurs like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs have imagined exciting ways to create new products, such as Microsoft’s Windows and Apple’s iPod, that enhance our enjoyment of life.

Occasionally, though, the imagination can run amok. Many corporate executives have given imagination a bad name when they’ve used theirs to get too creative with company revenue. One such example comes from financial innovators in the insurance industry. Several years ago, industry leader AIG began imagining a perfect world for its clients (and itself) in which they would always achieve Wall Street’s earnings expectations. Imagine, AIG must have thought, how happy clients would be if they never had to experience the indignity (and stock price decline) that accompanies an earnings shortfall.

And one day that dream became a reality. AIG and several other insurers began to market a new product called

finite insurance

. This magic solution would guarantee clients the ability to always produce earnings that were acceptable to Wall Street by “insuring against” earnings shortfalls. In a sense, this product was an addictive drug that allowed companies to cover up quarterly blemishes by inappropriately smoothing their earnings. And not surprisingly, customers were hooked. Everybody was happy. AIG found a new revenue stream, and customers found a way to prevent earnings shortfalls. However, there was a big problem: some of these “insurance” contracts were not really legitimate insurance arrangements at all; rather, they were actually financing transactions.

How Was Finite Insurance Abused?

Let’s turn to Indiana-based wireless company Brightpoint Inc. to see how some finite insurance transactions were economically more akin to financing arrangements. It was late 1998 and the bull market was racing, but Brightpoint had a problem: earnings for the December quarter were tracking about $15 million below the guidance given to Wall Street at the beginning of the quarter. As the quarter closed, management feared that investors would be unprepared for this news, and that, as a result, the firm’s stock price would be hammered.