Finding Arthur (41 page)

Authors: Adam Ardrey

Tags: #HIS000000; HIS015000; BIO014000; BIO000000; BIO006000

No other possible Avalon, not Glastonbury or anywhere else, has a viable historical Arthur living anywhere near it, far less evidence that the immediate antecedents of such an Arthur were buried there. The name Avalon only arrived on the scene in the twelfth century, six centuries after Arthur’s, that is, Arthur Mac Aedan’s death. During this time stories about Arthur that had originated in Scotland among Q-Celtic-speaking Gaels and P-Celtic-speaking Britons were taken south and subjected to Anglo-Saxon influences and later, after the Anglo-Saxons were conquered by the Norman-French in the eleventh century, to French influences. As a result we have the name Avalon, a name pleasing to French ears simply because French-influenced writers were holding the parcel when the music stopped: which is to say, when the name Avalon was finally fixed in writing.

Many people of the Old Way believed in magic cauldrons, just as many Christians believed Columba-Crimthann cast spells that imparted healing properties to bread.

17

It was said there was a magic cauldron of regeneration into which the dead were dipped before springing out to enjoy a new life on Iona. Magic cauldrons were common fictions and not exclusive to the Gaels and Picts.

The Gundestrup cauldron, found in a bog in Denmark in 1891, was probably a votive offering to the waters. The reliefs on the Gundestrup cauldron reflect the stories told of Iona’s cauldron—they show people being dipped into the cauldron and brought back to life. This cauldron story fits with the later fictions that have a dead or mortally

wounded Arthur taken to Avalon to be restored to active life. Iona fits these legends and more; it fits what Geoffrey says about nine women, because it was “By the breath of nine maidens it [the cauldron] was kindled.” Unless there is some other reason for this coincidence, these are the same nine sisters we left breathing on the fire beneath the cauldron on Iona.

What probably happened was something like this. Arthur died at or shortly after the Battle of Camlann and was taken by his soldiers and by women of the Old Way (perhaps nine maidens) to Avalon-Iona to be buried alongside his ancestors, according to the Old Way of the druids. And that is that. Arthur, Arthur Mac Aedan, was probably buried according to the Old Way, because his father was still king and Aedan was anti-Christian. It may be Columba-Crimthann and his monks had a part to play, just as Columba-Crimthann was allowed a small part in Aedan’s inauguration: in general, people of the Old Way were relatively tolerant.

All we can be sure about is that if Arthur’s body was dipped in a

magic

cauldron it did not work (because there are no such things as magic cauldrons or magic bread).

Malory may have written of women with black hoods taking Arthur away simply because black hoods were an obvious nice touch, given that Arthur was wounded and close to death, but this matter of women in black hoods has a basis in the history of Iona. Malory was an unscrupulous man who wrote fiction for personal gain and so cannot be relied upon, except to act in his own interest. He did however have access to historical sources that are now lost to us and which provided him with ideas that he certainly used. If he knew about Iona but did not refer to it directly because it undermined his southern Arthur project, he could also have used other similar source material, provided he disguised it adequately. Malory may have avoided mentioning nine women because nine women suggested the Old Way of the druids. He may have avoided mentioning Iona, because Iona was in the north, but if he knew about Iona, it may be he also knew about black-hooded women on Iona.

The Book of Clanranald

is a sporadic record of the Lords of the Isles that was kept by the family of Macvurich [

sic

]. It tells of Reginald,

son of the great Somerled, Lord of the Isles, who founded a nunnery of Black Nuns on Iona in the late twelfth century.

18

I am loathe to base any conclusion upon women’s fashions, of which I know little, and so I will say no more than this—if Malory knew of the Black Nuns of Iona, even as an anachronism, even if his information was secondhand, this may have inspired his black-hooded women. All we can be sure of is that Malory said black-hooded women took Arthur to Avalon and that there were still black-hooded women on Iona as late as 1543, well after Malory wrote

Le Morte d’Arthur

.

The Church bound Malory to inject Christian material into

Le Morte d’Arthur

, but his introduction of a hermit who was once an Archbishop of Canterbury always seemed somewhat weird to me.

19

How did he come up with that one? If Iona was Avalon that question is easily answered.

Columba-Crimthann was the second most famous Christian of his day, second only to Mungo Kentigern of Glasgow, and his fame increased as time passed. By the twelfth century when Benedictine monks took charge of Iona, they understood that it was in their interest to promote the cult of Columba-Crimthann and they did just that (even though Columba-Crimthann’s form of Christianity was markedly different from theirs). By Malory’s day, Columba-Crimthann would have been in the running to be considered the number one Scottish Churchman. Malory must have heard of Columba-Crimthann.

There was no shortage of hermits about Iona, indeed all over the highlands, in the sixth century: one of Iona’s top tourist attractions is the Hermit’s Cell. Adamnan said Columba-Crimthann lived in a hut or a cell on Iona,

20

but “saints” are always said to have lived simple lives and so this may not be true (remember, this was the same Columba-Crimthann who had someone running about after him when he was a student). Of course, it does not matter whether this is true or not: what matters is that it was said to be true and people believed it.

Malory’s fictional Archbishop of Canterbury, presented by Malory as a hermit, is not very different from Adamnan’s fictionalized version of Abbot Columba-Crimthann, presented by Adamnan as a humble monk. All Malory needed to do was delete the main Christian player on Iona at the time of Arthur’s death, Columba-Crimthann, and insert in his place the main English Christian player of his day, the Archbishop of Canterbury and … job done.

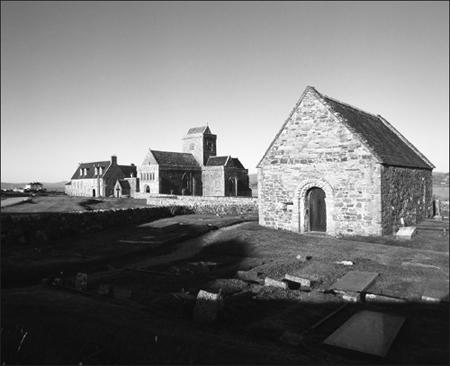

The Relig Oran, the graveyard where Arthur is buried, Iona-Avalon. To the right is Oran’s Chapel. To the left is Iona Abbey

.

©

Crown Copyright reproduced courtesy of Historic Scotland

.

www.historicscotlandimages.gov.uk

By making his Archbishop of Canterbury a retiree and a hermit Malory could explain how this cleric came to be away from Canterbury in Glastonbury. Notwithstanding the fact that the church tended to remember all its main men, right down to the most insignificant of saints (some of whom are

only

names), Malory’s Archbishop is anonymous. This anonymity was necessary because Malory’s Christian English

King Arthur is a figure of fiction (albeit one who is based upon a historical figure, Arthur mac Aedan) and because no Archbishop of Canterbury actually attended Arthur’s funeral.

L

ANCELOT

, G

UINEVERE, AND

M

ORDRED

Why is Arthur not the hero of his own legend? Almost by definition, the hero is the one who gets the girl and Arthur does not get the girl in the end of almost any of the stories. I know Ingrid Bergman flew off with Paul Henreid leaving Humphrey Bogart behind in

Casablanca

, but Humphrey could have had her if he wanted to (and probably did the night before the flight to Lisbon). In any case, Humphrey was more glamorous than Paul, which is all important. The legendary Arthur is not so blessed. He not only loses a wife he loves to Lancelot, his supposed best friend, but Lancelot is a better fighter and an all-round more exciting figure than Arthur, who is often presented as stolid and a bit dull, hardly the stuff of heroes. Why? Who was Lancelot?

Hussa of Bernicia, the Angle king at the time of the Great Angle War, died somewhere between 590 and 593, leaving his ineffectual son, Hering, to be ousted by his nephew or cousin, Aethelfrith. When Aethelfrith became king in Hering’s stead, Hering escaped from Bernicia and found refuge with Aedan in Dalriada, according to most sources. This is probably because Dalriada is most famously associated with Aedan’s name, but Manau makes more sense.

The evidence suggests that what happened was this. Hering sought sanctuary in Manau around 593, after he was run out of Angleland by Aethelfrith, and there tried to convince Aedan that he still commanded substantial support in Angle-land and that, if only Aedan would put him at the head of an army, he would recover what he, Hering, continued to think of as “his” kingdom. If he succeeded, Aedan would have an ally on the southern flank of the northern Gododdin. Unfortunately for Hering, even as he tried to persuade Aedan to help him, Aedan’s army, under Arthur, was engaged fighting the Picts and so action against Aethelfrith’s Angles was impossible.

It is easy to see that Aedan might have ordered Arthur to accept Hering into the ranks of his men, not because Hering was worthy of such a place but because he was a prince and princes are often elevated beyond their capacities simply because they are princes. Besides, Hering was still potentially useful to Aedan. Arthur might not have been happy about this, but Hering would have been pleased to be able to preen himself as one of Arthur’s

ArdAirighaich

.

After the Camlann campaign and Arthur’s death, everything changed. Aedan had to regroup and restore his standing among the peoples of southern Scotland. There was no prospect of his furthering Hering’s dream of a return to Angle-land, and so, again, Hering had to wait. When the Angles defeated the Gododdin at Catterick in 598, Hering must have despaired that he would ever be a king. Despite everything, five years later, Hering had his way when Aedan invaded Angle-land in Hering’s name and took on Aethelfrith.

The

Anglo Saxon Chronicle

tells the tale:

This year [603] Aedan, king of the Scots, fought with the Dalreathians, and against Ethelfrith, king of the Northumbrians, at Degaston, where he lost almost all his army. Theobald, brother of Ethelfrith, with his whole armament, was also slain. Since then no king of the Scots has dared to lead an army against this nation. Hering, the son of Hussa, led the enemy [that is, Aedan’s army].

21

It is unlikely that Aedan would have entrusted his army to a foreign prince despite what the

Anglo Saxon Chronicle

says. It is more likely Hussa was simply a figurehead. The

Anglo Saxon Chronicle

is notoriously parochial and especially unconcerned with events in Scotland, although in fairness to the chroniclers it was probably bruited about that Hering was at the head of Aedan’s army to divide the Angles and lessen the sense that this was an invasion by a foreign power.

This tactic did not work. Hering had overestimated his appeal to his “subjects,” as aristocrats almost always do. Aethelfrith’s army crushed Aedan’s Scots at the bloody Battle of Degaston fought near Dawston near Saughtree, just north of the battlefield of Arderydd.

Aedan’s men had become used to victory under Arthur, and so probably stayed too long upon the field and suffered extraordinary casualties, although not before they had destroyed one wing of the Angle army and killed Aethelfrith’s brother. No one knows what happened to the historical Hering, although, given that he would have been Aethelfrith’s main target, it seems likely he was killed in the battle.

Hering was from Berwick, fifteen miles from the “Holy Island” of Lindisfarne, where scholarly monks created beautiful books. Lancelot’s father, Ban of Benoic, is sometimes said to have lived on an island of scholars, an island that is sometimes said to be Mont Saint-Michel off the French coast. Berwick, Benoic; Lindisfarne, Mont St Michel; Hering, Lancelot—the connections are slight but they are there.

Christian clerics did not create the story of Lancelot and Guinevere’s adultery, because they did not approve of sex and would ignore it when they could. Their heroes were sexless knights like Galahad and Perceval. Secular writers created the Arthur-Guinevere-Lancelot love triangle. These Medieval storytellers, like modern storytellers, could recreate anything, and so when a southern hero was needed to dilute the legend of the Celtic Arthur and please their southern audience, they set out to find one.

Stories of Arthur had been transposed from the north to the south for centuries after Degaston, and so all southern storytellers had to do was find an Angle or a Saxon character in the world of Arthur. They found Hering, set to work, and produced Lancelot. He may never have been more than symbolically the head of Aedan’s army, but this, coupled with his having been numbered among Arthur’s, Arthur Mac Aedan’s, men, was enough for anti-Celtic, pro-“English” clerics to insert Hering into the growing Arthurian canon.