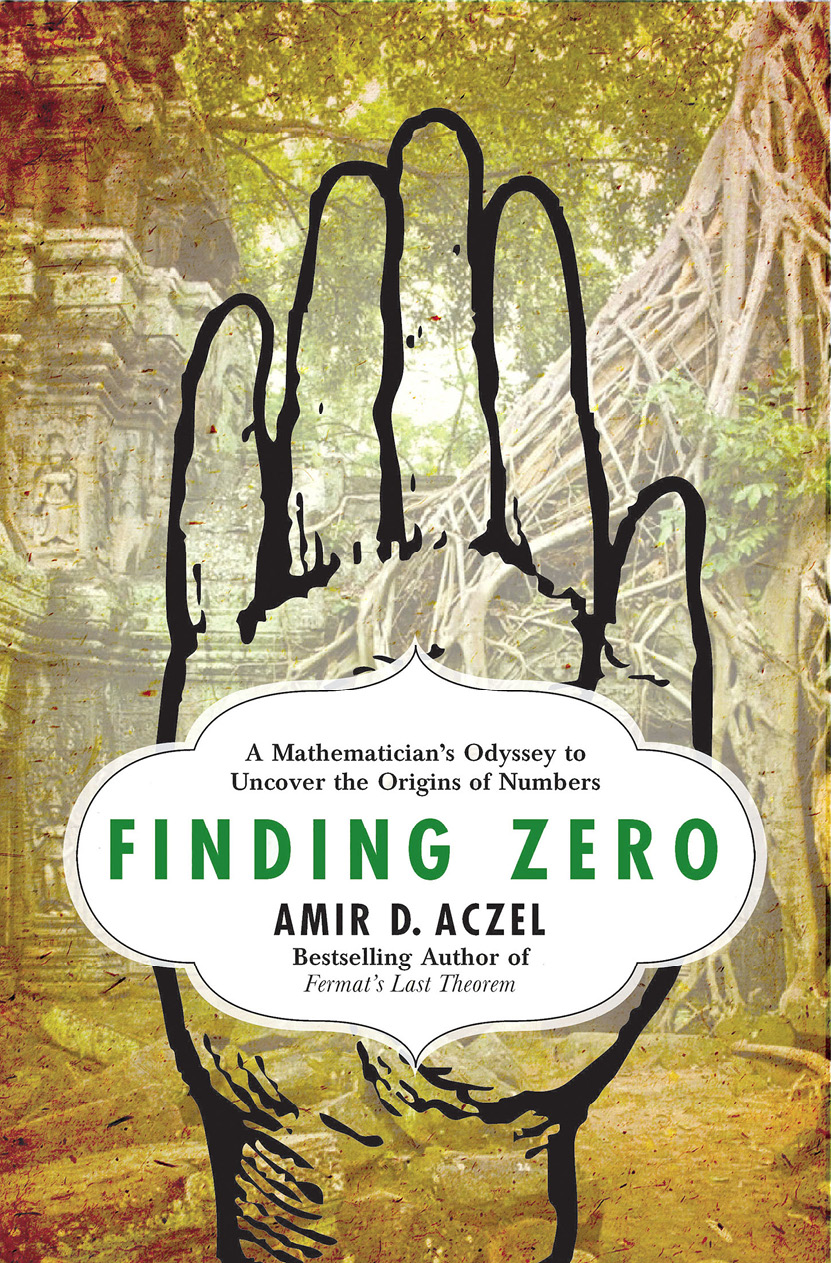

Finding Zero

Authors: Amir D. Aczel

Finding Zero

A Mathematician's Odyssey to Uncover the Origins of Numbers

Amir D. Aczel

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author's copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillan.com/piracy

.

For Miriam,who loves science

Introduction

The invention of numbers is one of the greatest abstractions the human mind has ever achieved. Virtually everything in our lives is digital, numerical, quantified. But the story of how and where we got these numbers we so depend on has been shrouded in mystery. This book tells the personal story of my lifelong obsession: to find the sources of our numbers. It briefly traces the known history of the very early Babylonian cuneiform numbers and the later Greek and Roman letter-numerals, and then asks the key question: Where do the numbers we use today, the so-called Hindu-Arabic numerals, come from? In my search, I explored uncharted territory, embarking on a quest for the sources of these numbers to India, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and ultimately to a jungle location in Cambodia, the site of a lost seventh-century inscription. On my odyssey I met a host of fascinating characters: academics in search of truth, jungle trekkers looking for adventure, surprisingly honest politicians, shameless smugglers, and suspected archaeological thieves.

When I entered first grade in the late 1950

s

, at a private school in Haifa, Israel, called the Hebrew Reali School, I was asked a question the institution always asked its entering students. My teacher, Miss Nira, a young and pretty woman who smiled a lot and wore long, bright-colored dresses, inquired of each of us six-year-olds what we hoped to learn in school. One child said “How to make money,” and another, “What makes trees and animals grow,” and when my turn came, I answered that I wanted to learn “Where numbers come from.” Miss Nira looked surprised and paused for a moment, and then without a word turned to the little girl sitting next to me. I wasn't a precocious child who comes up with a question the teacher cannot addressâI just had a most unusual childhood. And my answer to the teacher's question was a direct result of an experience I'd had during that special childhood.

My father was the captain of the SS

Theodor Herzl,

a cruise ship that sailed the Mediterranean at 21 knots, traveling from its home port in Haifa to the mythical islands of Corfu and Ibiza and Malta andâoftenâto fabulous Monte Carlo. One of my father's benefits as captain was the right to have his family join him on the

ship whenever he wanted. We took advantage of this privilege very frequently, so that I ended up attending school only part of every year, making up for lost class time with tutors and self-study and, once back at school, by sitting for deferred exams.

As soon as the

Theodor Herzl

would arrive at the charmed principality of Monaco, with its magnificent palace perched on a rock over the Mediterranean, my father would drop anchor and a fast motorboat would ferry passengers and crew ashore. At night, many would head to the great Casino de Monte Carlo by the water's edge near the center of town. This was the undisputed high-class gambling capital of the world. But minors like me were forbidden entry into the famed gaming rooms, where princes and movie stars and celebrities still try to woo Lady Luck. So while the adults from our ship, including my parents, played at the roulette tables, I was entertained by ship's stewards outside this white marble baroque palace surrounded by tall palm trees, bougainvillea, and white and red oleanders. There, my sister, Ilana, and I would run along the paths of this exuberant garden and play hide-and-seek among the fragrant bushes.

Ilana and I often fantasized about what it might be like inside this imposing building we thought we could never enter. Were people dancing? Were they eating fancy meals, as we often did aboard ship? We knew the adults played some kind of game insideâthey always talked about it afterward on the shipâbut what kind of game was it? We were dying to find out, and whispered about it between us.

And then one day it was my father's personal steward's turn to take care of us on the periphery of the casino. Laci (pronounced

“lotzi”), a Hungarian, concocted a scheme to take the girl of three and boy of five right inside the gaming halls. Laci was my favorite steward; the rest of them were boring middle-aged men who took care of us reluctantly (it wasn't really in their job descriptions). They were courteous and polite, but somewhat cold and formal. Whenever Laci took care of us, however, fun things would happen, and often rules of expected behavior were broken. “The boy needs his mother immediatelyâit's an emergency!” Laci hissed at the stern-faced, hulking, tuxedo-wearing bouncer at the door, and without waiting for an answer ushered us right inside the casino.

I was deathly worried about being kicked out. I knew the casino was taboo for us kids. But to my surprise nothing happened, nobody ran in to chase us away. I was dazzledâon the ornately carpeted floor I saw large, elegant tables covered in green felt, and on each one a checkerboard of numbers in red and black and one very special, round circle of a number alone in green. The atmosphere was heavy with cigar and pipe smoke, and I struggled hard not to cough.

I was excited to see my parents seated at one table. But I knew I dare not disturb them. So I kept very quiet, and didn't move. I feared this dream-come-true might end any minute.

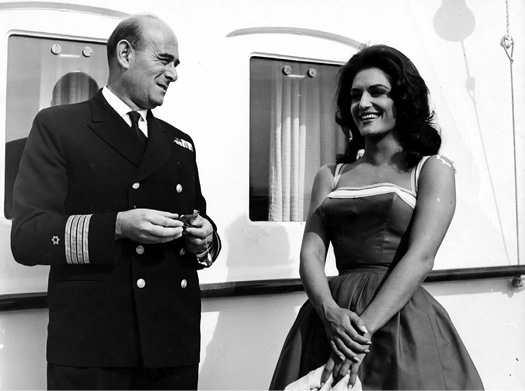

At the head of the table, across from the croupier, was my father, dapper in his black captain's uniform displaying numerous British wartime decorations, and next to him my mother, stunning in a light blue evening dress. They were flanked by a US congressman from a southern state on one side and the famous French-Italian singer Dalida on the other, both VIPs traveling

with us on this voyage. Other passengers were also seated around this table, and everyone was looking with rapt anticipation at a large black bowl at its center; at the bottom of the bowl was a spinning wheel.

My father, Captain E. L. Aczel, with the French-Italian singer Dalida, aboard ship off the coast of Monaco, 1957.

Their attention seemed focused on a little white ball that had been flung into the bowl by a man in a short black coat, a white collared shirt, and a black bow tie. Laci kept inching us closer until we stood right behind my parents. This was so excitingâto be at the heart of this magical activity forbidden to anyone younger than 21. Laci was holding my sister and me, each of us sitting on one of his arms; from our high vantage point above the table I could clearly see what was taking place below.

There was an eerie quiet as the ball twirled around in the bowl. I could hear every time it tapped a metal groove separating numbers at the bottom of the wheel, or when it struck one of the four diamond-shaped metal decorations above the numbers on the inner sides of the bowl, bouncing right back down whenever it did. I could feel the tension and anticipation. My father suddenly turned around when he noticed us, smiled knowingly at Laci, and then turned his attention back to the table.

“Look,” Laci explained to me in a whisper, “you see, these are numbers on the table, and notice that every one of them is also on the wheel. Now watch what happens.” I sat on his arm and stretched my neck forwardâI did not want to miss a thing. The little ball was still bouncing around in the bowl, but more slowly now. Soon it would come to a stop. But where? On which number would it land? Laci told me the ball could choose only one number to land on, since every number was separated from its neighbors by metal dividers. I tried hard to guess where the ball would end up as the wheel slowed down further. I could now make out the separate numbers marked on its bottom.

I was fascinated by these colorful numbersâornate signs that beckoned me by their mystery, and which as I matured I would understand to represent fundamental abstract concepts that rule our world. I will never forget their shapes on that velvet board. I fell in love with their magic, associating them in my mind with something alluring and forbidden, an unknown pleasure awaiting discovery. The ball finally made one last bounce and came to a stop right on the number seven. Suddenly, a commotion erupted at the

table. Across from us an elderly woman in a bright yellow evening gown jumped up from her seat and cried, “Yes!” Every head turned toward her. Some players, perhaps vicariously sharing her big win, congratulated her. Others, maybe envious and upset they had lost, expressed their disappointment.

The croupier forked over a large heap of chips of different colors, the smaller ones round and the bigger ones rectangular with large numbers visible on their faces; I understood these pieces of plastic represented money, each color and shape a different amount. Not knowing much about money at my age, I still could sense by the number and size of these chips, and by the continuing excitement around the table, that this woman had become rich. Laci explained to me that the croupier was giving her many times more than the wager amount since she had bet on a single number. I looked at her, noticed the elation in her face, the happy smile, and heard her rapturous exclamations: “I won! I won!”

Then Laci muttered, as if to himself, “Seven, a prime number.” I was curious to know what this meant. Laci always had important things to say, and I knew this whispered exclamation had some meaning.

Later, Laci became my self-appointed math tutor on the ship; he taught me also about prime numbers. They would become a lifelong fascination. One day, having observed Laci teaching me math for some time, my mother asked my father how come he knew so much about the subject. My father told her that Laci had been a brilliant mathematics graduate student at Moscow State University right after the war, but that there had been a big scandal about his research having to do with secret information, perhaps

even a suspicion of espionage, and under pressure from the KGB the university asked him to leave. The episode was shrouded in mystery; Laci never talked about it, and nobody knew any details.

But Laci apparently got his revenge on the Soviets, for what happened next was well-known and published in all the newspapers. After he quit his studies, he went to Czechoslovakia to learn to fly military airplanes. Then, in 1948, the Jews of the fledgling state of Israel found themselves attacked by the surrounding Arab states. Laci heard that they badly needed airplanes, so this non-Jew sneaked into the pilot's seat of one of the Czech planes he had been training on, took off, and flew it alone all the way to Israel, handing it over as a gift to the newly founded Israel Air Force.

Then, having nothing else to do in this new land, Laci started working for the shipping company Zim Lines and eventually became my father's steward. Both were Hungarian and shared bonds of common heritage, outlook, and lifestyle. (Incidentally, the

Theodor Herzl

was named after another Hungarian, whose political theory had laid the groundwork for Israel's founding.) My father and Laci were close, and Laci took seriously his role as the captain's steward and was never too far from him. Given his clout aboard ship as the crewmember closest to the seat of power, everyone wanted to be his friend. This was his new life, but Laci never lost his love of mathematicsâand he taught me much about it over the years.

“So where do these numbers come from?” I asked him when he put my sister and me to bed on the ship the night of the big casino adventure. “It's a mystery,” he answered. “We don't really know.” And since Ilana and I were wound up from having been up

late in a place we'd always dreamed of entering, he told us part of what he did know as our bedtime story.

“We call these numeralsâthat's the name for the shapes of the numbers you sawâArabic,” he said, “or sometimes Hindu, or even Hindu-Arabic. But when your father and I were once detained with the rest of the ship's crew in an Arab port city, I spent my time there learning the numerals the Arabs use today.” He then opened a drawer and took out a piece of the ship's stationery and drew on it in large print all ten Arabic numerals. “You see,” he said, “they look nothing like the numbers we saw on the tables tonight, the numbers we know so well.” I looked at these numbers in amazement. I'd never seen such signs. Only the one looked like our 1; the rest of the shapes were totally foreign to us. The five was a small uneven circle, and the zero a dot. I tried to copy the drawn numbers but didn't do too well.

Then Laci took out a deck of cards he had brought with him and placed them face up on a table. I tried to read all their numbers, and little Ilana played with them, turning around the ornately drawn kings, queens, and jacks in black and red. Ilana noticed that they looked the same when upside down. Finally, after playing with these wondrous numbers and shapes for perhaps half an hour, we fell asleep.

The next night, Laci came again to put us to bed. My sister and I shared a cabin next to the captain's, where my parents slept and where we spent our days. “Today let's talk more about the numbers,” he said. “So you remember that they don't look very much like the Arabic numerals. Well, guess what: They are not like the Hindi numbers either.” Then on a new piece of stationery he

drew the Hindi numbers, which some people in India use today, and explained that similar signs are in use in Nepal and Thailand and other Asian countries. “I learned this,” he said, “also from experience, when our ship docked at Bombay a few years ago on a world cruise.”

I looked at these curious numbers and tried to copy them, and my sister made some drawings. We all laughed at my attempts until we children fell asleep. The following night, I had many questions for Laci about the origin of the numbers: “Where do these numbers really come from? Why don't we use the Arabic numbers? Why do different peoples have their own different numbers? And who invented them all?” I wanted answers right awayâI was so curious, so fascinated by them, that I could think of nothing else.

Laci's answer disappointed me a little. All he said was, “Why don't you ask your teacher when you start school next month.” This was painful for me to hear. It was late August then, and I knew that, sadly, I would soon have to leave the ship with my mother and sister for at least a few months of school before we could rejoin my father for more cruising. I would miss Laci and the stimulating conversations we had almost every day about ships and ports and cities and sailingsâand about numbers.