Firebirds Soaring (2 page)

Authors: Sharyn November

So what’s next for Firebird? Well, more good books, of course—I am perennially looking for non-dystopian science fiction. Help me!—and more anthologies, if you’ll have them, and surprises where I can fit them in.

Of course, I want to know what you think of

Firebirds Soaring

. Please e-mail me at

[email protected]

. I actually do read all of the e-mail I receive and take your suggestions into account, so let me know what you think I should be publishing, what’s missing in the marketplace, what we’re doing right, and what we could do better. This is your imprint as much as anyone’s, remember.

Firebirds Soaring

. Please e-mail me at

[email protected]

. I actually do read all of the e-mail I receive and take your suggestions into account, so let me know what you think I should be publishing, what’s missing in the marketplace, what we’re doing right, and what we could do better. This is your imprint as much as anyone’s, remember.

Speaking of which: you named this book. The acknowledgments in the back will tell you everyone who sent me

Firebirds Soaring

as a possible title. Thank you.

Firebirds Soaring

as a possible title. Thank you.

And, as always, thanks for reading Firebird books, and allowing me to publish more of them!

Sharyn November

January 2009

January 2009

Nancy Springer

KINGMAKER

D

estiny, I discovered upon a fateful day in my fif-teenth year, can manifest in small matters.

estiny, I discovered upon a fateful day in my fif-teenth year, can manifest in small matters.

Tedious matters, even. In this instance, two clansmen arguing about swine.

Barefoot, in striped tunics and baggy breeches, glaring at each other as if they wore swords instead, the two of them stood before me where I sat upon my father’s throne. “His accursed hogs rooted up the whole of my barley field,” complained the one, “and there’s much seed and labor gone to waste, and what are my children to eat this winter?”

“It could not have been my hogs,” declared the other. “I keep iron rings in my pigs’ snouts.”

“Better you should keep your pigs, snouts and all, where they belong. It was your hogs, I’m telling you.”

Outdoors, I thought with a sigh, the too-brief summer sun shone, and my father, High King Gwal Wredkyte, rode a-hawking with his great ger-eagle on his arm and his nephew, Korbye, at his side. Meanwhile, in this dark-timbered hall, I held court of justice in my father’s stead. No easy task, as I am neither the high king’s son nor his heir; I am just his daughter.

My cousin Korbye is his heir.

But I could give judgment and folk would obey me, for I had been guiding my father’s decisions since I was a little girl, sitting upon his knee as I advised him who was telling the truth and who was lying. In this I was never mistaken.

This is my uncanny gift, to know sooth. When I lay newly born, I have been told, an owl the color of gold appeared and perched on my cradle. Soundlessly out of nowhere the golden owl flew to me, gave me a great-eyed golden stare, and soundlessly back to nowhere it flew away, all within my mother’s closed and shuttered chamber. “This child will not die, like the others,” she had whispered from the bed, where she lay weak after childbirth. “This child will live, for the fates have plans for her.”

If those plans were only that I should sit indoors, on an overlarge chair draped with the skins of wolf and bear, listening to shaggy-bearded men quarrel, I wished the fates had kept their gift.

The accused clansman insisted, “But it cannot have been my pigs! They can’t root, not with rings the size of a warrior’s armband through their noses.”

“Are you telling me I’m blind? You think I don’t know that ugly spotted sow of yours when I see her up to her ears in the soil I tilled? Your pigs destroyed my grain.”

I asked the accuser, “Did you see any swine other than the spotted sow?”

“His sow destroyed my grain, then.”

“Answer what I asked.”

“No, I saw only the spotted sow. But—”

“But how could one sow root up the whole of a field by herself?” cried the other clansman. “With a ring in her snout? It could not be so, Wren!”

I scowled, clouds thickening in my already-shadowed temper. I possess a royal name—Vranwen Alarra of Wredkyte—yet everyone, from my father to the lowliest serving boy in his stronghold, calls me Wren. Everyone always has, I suppose because I am small and plain—brown hair, brown eyes, clay-dun skin—but plucky in my stubby little way. Although no one, obviously, is afraid of me, or they would not bespeak me so commonly.

“Wren, I am not a liar!” insisted the clansman with the ruined barley field.

I held up my hand to hush them. “You both speak the truth.”

“What!” they exclaimed together.

“You are both honest.” My sooth-sense told me that, as sometimes chanced in these quarrels, both men believed what they had said. “The real truth flies silent like an invisible owl on the air between you two.”

“But—but . . .”

“How . . . ?”

But how to resolve the dispute? they meant.

Customarily, in order to pass judgment, I would have closed my eyes and cleared my mind until my sooth-sense caught hold of the unseen verity. But on this day, with my father and my cousin out riding in the sunshine, I shook my head. “I will sit in the shadows no longer. Come.” I rose from the throne, beckoning dismissal to others hunkered against the stone walls; they could return on the morrow. “Show me this remarkable spotted sow.”

Surely, striding out on the moors, I looked not at all like a scion of the high king, the sacred king, Gwal Wredkyte, earthly avatar of the sun. I, his daughter, wore only a simple shift of amber-and-brown plaid wool, and only ghillies, ovals of calfskin, laced around my feet. No golden torc, no silver lunula, nor am I royal of stature or of mien.

Nor did I care, for I felt like a scullery girl on holiday. Laughing, I ran along the heathery heights, gazing out upon vast sky and vast sea, breathing deeply of the salt-scented wind making wings of my hair.

“Take care, Wren,” one of the clansmen called. “’Ware the cliff’s edge.”

He thought I had no more sense than a child? But my mood had turned so sunny that I only smiled and halted where I was, not so very near to where the heather ended, where sheer rocks plummeted to the breakers. Long ago, folk said, giants had carved these cliffs, playing, scooping up rocks and piling them into towers. Atop one such tower nearby balanced a stone the size of a cottage, rocking as gently as a cradle in the breeze that lifted my hair. It had teetered just so since time before time, since the giants had placed it there.

“Wren,” urged the other clansman, “ye’ll see my pigsty beyond the next rise.”

Sighing, I followed.

A sturdy circle of stone it was, but no man has yet built a pen a hog cannot scramble out of. For this reason, and because swine require much feeding, customarily they roam from midden heap to midden heap, gobbling offal, with stout metal rings in their snouts to tug at their tender nostrils if they try to root. Otherwise, they would dig up every hands-breadth of land in search of goddess-knows-what, while the geese and sheep and cattle would have no grazing.

Laying my forearms atop the pigsty’s stone wall, I looked upon the denizen.

The accused, doubly imprisoned. Tethered by a rope passed through the ring in her nose.

There she lay, a mountainous sow, unmistakable, as the complaining clansman had said, because of her bristly black skin splotched with rosettes of gray as if lichens grew on her. A great boulder of a sow, all mottled like a sable moon. Shrewd nosed and sharp eared, with flinty eyes she peered back at me.

I felt the force of something fey in her stare.

Almost whispering, I bespoke her courteously, asking her as if she could answer me, “Are you the old sow who eats her farrow?” For such was one of the forms of the goddess, the dark-of-the-moon sow who gives birth to a litter, then devours her young.

I sensed how the clansmen glanced at each other askance.

The great pig growled like a mastiff.

The clansman who owned her cleared his throat, then said, “You see the ring in her nose, Wren?”

“Yes. She looks disgruntled.” Still oddly affected, off balance, I tried to joke, for a

gruntle

is a pig’s snout—the part that grunts—so

disgruntled

could mean a hog with its nose out of joint, as might be expected when a ring of iron—

gruntle

is a pig’s snout—the part that grunts—so

disgruntled

could mean a hog with its nose out of joint, as might be expected when a ring of iron—

I stared at the ring in the sow’s snout, all jesting forgotten.

No ordinary swine-stopper, this. Despite its coating of mud, I saw flattened edges and spiral ridges like those of a torc.

“Where did you come by that ring?” I demanded of the owner.

“Digging turf one day, I found it in the ground. She needed a new one, hers was rusting to bits, so—”

“I want to see it. Come here, sow.” Reaching for the rope that tied her, I tugged.

“She won’t move for anything less than a pan of buttermilk.”

But as if to make a liar of him after all, the sow heaved herself up and walked to me.

Reaching over the stone wall, with both hands I spread the ring and took it from her snout, feeling my heartbeat hasten; in my grasp the ring felt somehow willful, inert yet alive. It bent to my touch, so I fancied, gladly, then restored itself to a perfect circle after I had freed it from the pig and from the rope.

Still with both hands, as if lifting an offering to the goddess, I held the dirt-caked circle up in the sunlight, looking upon it. Pitted and stained it was, but not with rust. Rather, with antiquity.

“That’s no ring of

iron

, fool,” said the complaining clansman to the other one.

iron

, fool,” said the complaining clansman to the other one.

“Some softer metal,” I agreed before they could start quarreling again. And although my heart beat hard, I made as light of the matter as I could, slipping the ring into the pouch of leather that hung at my waist, at the same time feeling for a few coppers. I would gladly have given gold for that ring, but to do so would have excited the jealousy of the other clansman and caused too much talk. So with, I hoped, the air of one settling a matter of small importance, I handed threepence to the sow’s owner and told him, “Get a proper ring to put in her snout. Then she will trouble your neighbor no more.” To the other man, also, I gave a few pence, saying, “If your children grow hungry this winter, tell me and I will see that you have barley to eat.”

Then I left them, striding home as if important business awaited me at the stronghold.

In no way could they imagine how important.

All the rest of that day I closeted myself in my chamber, with the door closed and barred, while I soaked the ring in vinegar, scrubbed it with sweet rushes, coaxed grime from its surface with a blunt bodkin, until finally by sunset glow I examined it: a simple but finely wrought thing made not of iron or copper or silver or gold, but of some metal that lustered even more precious, with a soft shifting green-gray glow, like moonlight on the sea. Some ancient metal I did not know—perhaps orichalcum? Perhaps this had been an armband for some queen of Atlantis? Or perhaps a finger ring of some giant who had long ago walked the heath and built towers of stone?

Such an ancient thing possessed its own mystery, its own power.

Or so my mind whispered.

Was I a seer as well as a soothsayer? The odd sort of recognition I had felt upon seeing the black moon-mottled sow had occurred within me at intervals all my life, although never before had I truly acknowledged it. Or acted upon it.

Perhaps I was an oracle. Druids said that the wren, the little brown bird that had fetched fire down from the sun for the first woman, possessed oracular powers.

I should feel honored to be called Wren, my mother had often told me while she still lived, for the wren is the most beloved of birds. It is a crime to harm a wren or even disturb a wren’s nest. Except—this my mother did not say, but I knew, for I had seen—once a year, at the winter solstice, the boys would go out hunting for wrens, and the first lad to kill one was declared king for the day. They would troop from cottage to cottage, accepting gifts of food and drink, with the mock king in the fore carrying the dead wren. Then they would go in procession to the castle, and the real king would come out with the golden torc around his neck; the dead wren would be fastened atop an oaken pole, its little corpse wreathed with mistletoe, and a druid would carry it thus on high while the king rode behind with his thanes and retainers in cavalcade. Therefore the wren was called the kingmaker.

As I thought this, glad shouts sounded from the courtyard below: “High king! High king!” Gwal Wredkyte and his heir Korbye and their royal retinue had returned from hawking.

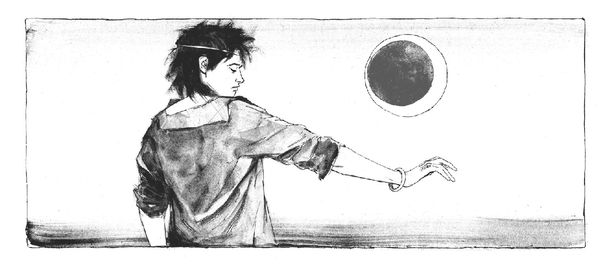

Although I seldom adorned myself, this day I took off my simple shift and put on a gown of heavy white silk edged with lambswool black and gray. I brushed my hair and plaited it and encased the ends of the braids in clips of gold. I placed upon my head a golden fillet. Around my neck I hung a silver lunula, emblem of the goddess.

For a long time I looked at myself in my polished bronze mirror that had been Mother’s before she died.

Finally I took my newfound treasure—a ring the size of a warrior’s armband, just as the black sow’s owner had said—and I slipped it onto my left arm up to my elbow, where it hid itself beneath the gown’s wide sleeve.

Other books

Worth It All (The McKinney Brothers #3) by Claudia Connor

The Executive’s Affair Trilogy Bundle (Trinity, Desire, Unconditional) by Nelson, Elizabeth

Demon Squad 7: Exit Wounds by Tim Marquitz

Gandhi & Churchill by Arthur Herman

The China Dogs by Sam Masters

A Cowgirl's Christmas by C. J. Carmichael

The Andalucian Friend by Alexander Söderberg

Loren D. Estleman - Amos Walker 21 - Infernal Angels by Loren D. Estleman

As I Wake by Elizabeth Scott

Forged by Erin Bowman