Firebirds Soaring (8 page)

Authors: Sharyn November

The fireflies glow off and on in the mist-covered fields, calling out,

Here I am

, waiting for another light to appear in the darkness.

Here I am

, one calls to another.

Come find me

.

Here I am

, waiting for another light to appear in the darkness.

Here I am

, one calls to another.

Come find me

.

Here I am.

After two years an English teacher in Japan,

CHRISTOPHER BARZAK

has returned to his home state of Ohio, where he teaches writing at Youngstown State University. His stories have appeared in the anthologies

The Coyote Road, Salon Fantastique, Interfictions,

and

The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror

, among others. He is also the author of

One for Sorrow

, his Crawford Award-winning debut novel, and

The Love We Share Without Knowing.

CHRISTOPHER BARZAK

has returned to his home state of Ohio, where he teaches writing at Youngstown State University. His stories have appeared in the anthologies

The Coyote Road, Salon Fantastique, Interfictions,

and

The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror

, among others. He is also the author of

One for Sorrow

, his Crawford Award-winning debut novel, and

The Love We Share Without Knowing.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

When I was living in Japan, I was given a children’s book as a gift by one of my fourth-grade classes. Everyone in the school system where I taught—a small rural community outside the suburbs of Tokyo—knew I was trying my best to learn Japanese, so the book

Gongitsune

—a staple for fourth-graders in Japan (which happened to be my reading level in Japanese at that time)—was a perfect gift. I fell in love with the story of Gon the fox, as he’s called affectionately in Japan, and the lessons he learns and that he teaches others. The artwork was some of the most fabulous depictions of a fox—an animal thought to be a magical creature in Japanese mythology—I’d ever seen. It made me curious, and my curiosity led me to read further into fox lore, and the further in I went, the more I wanted to write about a young girl who is, in fact, a fox spirit but does not know her own origins and powers immediately, the way we’re all born into our lives here without knowing where we come from, why we’re here, or where we’re going.

Gongitsune

—a staple for fourth-graders in Japan (which happened to be my reading level in Japanese at that time)—was a perfect gift. I fell in love with the story of Gon the fox, as he’s called affectionately in Japan, and the lessons he learns and that he teaches others. The artwork was some of the most fabulous depictions of a fox—an animal thought to be a magical creature in Japanese mythology—I’d ever seen. It made me curious, and my curiosity led me to read further into fox lore, and the further in I went, the more I wanted to write about a young girl who is, in fact, a fox spirit but does not know her own origins and powers immediately, the way we’re all born into our lives here without knowing where we come from, why we’re here, or where we’re going.

I modeled the young woman in the story on two girls from my classes—one was the young girl in that fourth-grade classroom who’d been selected to present me with the book, and the other was her older sister, one of my ninth graders. They were both feisty and rule-challenging, which is sometimes a rare quality in Japanese girls, who are encouraged to be quiet and well-mannered. Writing about Midori in this story, I kept these two sisters in my mind and hoped they wouldn’t ever lose their challenging spirits as they grew older and began to make their own lives.

Chris Roberson

ALL UNDER HEAVEN

L

u Yumin stood on the Ting township dock, waiting for his grandmother to arrive, as the sun rose over the still waters of the Southern Sea. A skink skittered over his foot, breaking his concentration on the red-and-gold object in his hands. Skin crawling, he shook all over and cursed the little gray-green aquatic lizards that swarmed the dock.

u Yumin stood on the Ting township dock, waiting for his grandmother to arrive, as the sun rose over the still waters of the Southern Sea. A skink skittered over his foot, breaking his concentration on the red-and-gold object in his hands. Skin crawling, he shook all over and cursed the little gray-green aquatic lizards that swarmed the dock.

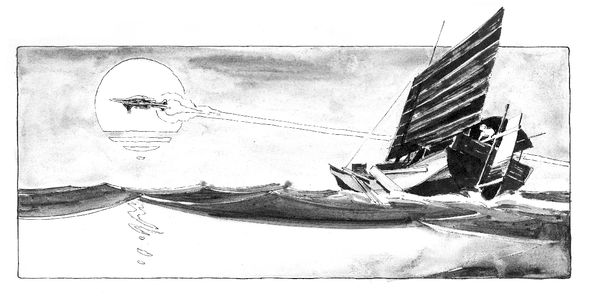

A junk had just put out from the dock, motoring away from shore, the hands scrambling in the rigging to unfurl its square sails, each emblazoned with the image of a stylized red lantern. One of the crewmen was aft, and he cupped his hands around his mouth to shout over the motor’s noise. “Get moving, Grandmother Lu! Or would you prefer we bring you back some fish when we’re done?”

The other crewmen of the junk laughed raucously. Yumin sighed deeply and turned to see the old woman coming up the dock toward him, a heavy mesh bag slung over her shoulder, a pipe clenched in her teeth.

“The stage suffered the day that Ling Jun chose to become a sailor, no?” Grandmother scowled and made a rude gesture with her free hand toward the retreating junk. “The idiot. Ten years as first mate on my boat, and he takes a post with the Red Lanterns scrubbing decks. If he’d stuck with me, he’d have his

own

boat by now.”

own

boat by now.”

Yumin shrugged and turned his attention back to the device in his hands, trying to work out what was preventing it from operating.

“Ever since you found that thing in the rubbish pile last month,” Grandmother said, drawing nearer, “I think you’ve scarcely been without it.”

“It’s something to do with my hands, I suppose,” Yumin answered sheepishly.

“Now look, Daughter’s-son.” As Grandmother shooed a few skinks out of the way with the toe of her boot and dropped the bag to the planks of the dock, Yumin’s nostrils caught the strong scent of ginger that followed her everywhere like a cloud. “I’ve never stood in the way of your tinkering, and God knows that I’m grateful enough for it when the junk’s engines give out, but you’ve been spending more time at your hobby than your job, and it’s got to stop. I’ve cut you some slack since your mother died, but now I need your head and hands both back at their jobs. It’ll just be you and me on this trip.”

From the deck of Grandmother’s junk came the sound of wet flesh slapping wood, and they turned to see a pair of otters, their forelegs propped up over the boat’s railing. One, with a nick in his ear, waved his paws, signing furiously.

Grandmother sighed. “Yes, Genius, just me and Yumin and you and Recluse, of course.”

Recluse, the other otter, nodded his small head, signing the gestures for laughter, while Genius ran in a tight circle, slapping the deck with his paws and tail.

“Clowns.” Yumin shook his head.

A squawk came from overhead.

“And you, too, Great Sage,” Grandmother called up to the cormorant perched atop the mast, “you feathered pillow, you.”

The cormorant clacked its beak, an avian sort of laugh, and then returned to preening its feathers.

“Here, take this, boy.” Grandmother pushed the bag of supplies over to Yumin with the side of her foot, and then vaulted nimbly to the deck of the junk.

Yumin tucked the device inside his tunic, and then handed the bag over, careful not to let the supplies fall into the cold waters.

“Hurry up now. We need to get on the open water before midday, or else the Red Lanterns will have caught all of the fish before we catch a one.” To Yumin’s surprise, Grandmother said the name of their rivals with scarcely a moue of distaste.

Yumin untied the junk from the dock and, with a final glance back at the town, jumped the gap, landing on the deck with a thud. He had just five more days before he needed to be back, or so the recruiting officer had said. Five days to spend one last trip with his grandmother, and then break her heart.

Once they’d motored far enough away from the shore, Grandmother cut the engines and let the sails catch the wind, propelling them out into the waters of the Southern Sea.

At the wheel, Grandmother puffed on her pipe and called over to Yumin, tinkering with his device in the prow. “I want to drop anchor near the Sunken City by nightfall and be in position to release the nets before dawn.”

The Sunken City

, Yumin thought. Would this be his last time to see its faint lights?

, Yumin thought. Would this be his last time to see its faint lights?

“You hear me, Yumin? Or have your brains fallen into that little red box of yours?”

“I heard you, Grandmother.” Yumin tried not to sound like a petulant child, but succeeded only partially.

The Sunken City had a name, once, but no one used it now. Before the water levels of the Southern Sea had risen to their current height, when it was only a lake a few hundred meters deep, the Sunken City had perched at its shores. It was a port city, a hub for travel and home to fishers, and also the place where all of the creatures of the Southern Sea were first hatched and adapted for life on Fire Star. Most had originally been aquatic strains brought to Fire Star once the red planet had been sufficiently terraformed to support aquatic life. Many of the species had been modified over the generations, their genes twisted and turned until they were better suited to survive on the red planet, and some, like Grandmother Lu’s otters and cormorant, had even had their intelligence and aptitudes boosted. When the water levels rose even higher, as the red planet grew ever warmer, the Sunken City was claimed by the waves, and as the coast migrated inland to the borders of Ting township, it had become the new port.

“You know, Grandmother . . .” Yumin said, at length. “About the Red Lantern Families . . . ?”

“Yes, what of them?” Grandmother answered, guardedly.

“Well, it seems to me that the main reason they’re so successful is their automation. If you were to automate your operation, you wouldn’t need to hire extra hands. In fact, if you sprang for one of the mechanical intelligent central controllers that are now available, you wouldn’t have to go out on the waters at all, but could instead stay at home and relax while the automated systems did all of the work for you.”

Grandmother blew air through her thin lips, making a sound like flatulence. “That isn’t real fishing. And besides, it’s automated systems like the Red Lantern Families that are fishing the Southern Seas empty. That’s why the fish have been so scarce. Machines that don’t need to eat and sleep, that catch more fish than the market can buy, driving down prices for everyone else. Besides, I’ve got the otters and the cormorant and you to help me, so why do I need to spend a fortune on automata just to haul in the nets? We’ll do just fine, as we always have.”

Yumin sighed, and turned back to the red-and-gold brick.

That night, they dropped anchor, and Yumin was so tired that he went straight to sleep after their evening meal, climbing into his bunk in the hold before the sun had completely set.

How long he slept, Yumin wasn’t sure, but sometime in the middle of the night he was roused from his slumber by the sound of something large bumping the bottom of the boat. Yumin scrambled out of his bunk and up on deck, but Grandmother was already there, smoking her pipe and peering over the side of the junk.

They could see nothing in the dark waters except glittering lights far below the surface.

“The Sunken City,” Yumin said. He knew that the lights were just bioluminescent algae, cultured and engineered when the submerged city had been a living metropolis, but still, seeing them by moonlight, he couldn’t help but be reminded of the bedtime stories of his grandmother, before he claimed to have outgrown such things, about the Land in the Sea, a glittering kingdom at the bottom of the ocean, ruled over by a magical dragon.

Grandmother puffed her pipe, the burning ember in the bowl glowing red like a hot coal, casting an eerie red light on her careworn features, but said nothing.

They were back at work before sunrise. The cormorant wheeled overhead but squawked that it couldn’t see any sign of shoals beneath the water.

“That’s a bad sign,” Grandmother said, but she didn’t have to explain what she meant. Fish had always congregated around the structures of the submerged city, finding shelter to feed, and to reproduce, in buildings that once housed humans and their machines. If there were no fish to be found here, it was not a promising indicator that they would have much luck in other locales.

“What do we do, Grandmother?”

“Well, there’s nothing to be gained from standing here and gawking. We’ll send Great Sage out to range a bit farther afield”—she flashed a few signs at the cormorant, who squawked in response, then flew off in a wide arc, heading toward the east—“while we start trawling here. It’ll be only for individual fish, at best, but it beats waiting around on our backsides.”

With Grandmother’s help, Yumin released the nets, two large sets of mesh hooked to strong lines that ran over pulleys on a high gantry in the junk’s rear, ending in wide spools attached to a motor. When the nets were in place, Grandmother took the wheel and started up the engine. The boat moved in wide circles, marking out the limits of the Sunken City far below. If there’d been shoals in these waters, the otters would have been put to work, herding the fish in their dozens and hundreds into the nets. With only scattered fish to be had, their talents wouldn’t be needed, so they sat on the prow of the junk, leaning into the spray, luxuriating in the warm sum.

When they’d made a full circuit, Grandmother cut the engine, and Yumin kicked the lever that started the motor spooling in the nets. When the nets had been reeled in and were hanging from the gantries overhead, Yumin was dispirited to see only one or two fish sporadically flopping in the heavy mesh.

“Keep heart, Daughter’s-son,” Grandmother said brightly. “We’ll catch them yet.”

Yumin sighed. He’d hoped to fill the hold with a big haul right away so they’d be forced to head back into port sooner rather than later. Then he could tell Grandmother his news when they were nearly in reach of home, and there’d be less chance that he’d miss his transport.

“Look there.” Grandmother pointed overhead with the stem of her pipe.

The cormorant came angling in from the east, frantically flapping his wide wings, and gracelessly landed on his perch at the mast’s top.

“Well?” Grandmother shouted impatiently up at the bird.

The cormorant shivered, and squawked in his simple syllables that he had sighted something in the water to the east. It seemed to Yumin that the bird was agitated, even nervous. “Grandmother, does Great Sage seem . . . distressed, to you?”

Other books

Bienaventurados los sedientos by Anne Holt

Loving Her by Jennifer Foor

Texas Heat by Barbara McCauley

Return of the Prodigal Son by Langan, Ruth

Zombie Lovin' by Olivia Starke

Trains and Lovers: A Novel by Alexander McCall Smith

Cruise by Jurgen von Stuka

CheckMate (Play At Your Own Risk) by Mickens, Tiece

A Bit of Earth by Rebecca Smith

The Flux Engine by Dan Willis