First Jihad: Khartoum, and the Dawn of Militant Islam (12 page)

Read First Jihad: Khartoum, and the Dawn of Militant Islam Online

Authors: Daniel Allen Butler

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: HIS027130

BOOK: First Jihad: Khartoum, and the Dawn of Militant Islam

10.54Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

His ascent to the position of Prime Minister was steady if not spectacular.

He formed the first of his four governments in 1868, when his tenure would last for six years.

It was a term of office memorable for the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland, a measure designed to pacify Irish Roman Catholics by reliving them of the necessity of paying tithes to support the Anglican church, as well as significant land reforms for Ireland meant to protect tenant farmers facing eviction by absentee landlords.

The Emerald Isle would prove to be a recurring theme in Gladstone’s career, and the question of Home Rule for Ireland would eventually bring the fall of his final government in 1894.

Gladtone was a reformer at heart: he utterly believed that the role of a nation’s government was to do its utmost to improve the lives of its people.

He would close his career proud of what he had achieved for Britain’s middle and working classes.

Among his reforms were the vote by secret ballot, a reorganization of Britain’s civil courts, expansion of education, the introduction of competitive admission to the civil service, and abolition of the sale of commissions in the army.

Foreign policy, however, was his weakness, for he was not as interested in the great questions of imperialism and empire as was his Conservative rival, Benjamin Disraeli.

Here Gladstone’s conscience and morality was a handicap, for he was unable to adopt what he felt was a hypocritical pose by turning a blind eye to the excesses of other nations whenever it was convenient for Great Britain’s imperial interests to do so.

The year 1876 saw Gladstone publish a pamphlet,

Bulgarian Horrors and the Questions of the East

, attacking the Disraeli government for its indifference to the Turks’ brutal repression of the Bulgarian rebellion, and his continued attacks on Disraeli’s aggressively imperialist policies brought the Liberals back to power in 1880.

During his second tenure as Prime Minister, Gladstone would be able to pass an even more effective Irish land act, along with two parliamentary reform bills which further extended the franchise and redistributed the seats in the House of Commons.

But the overshadowing issue of Gladstone’s second government, which would ultimately bring it down, was the fate of the city of Khartoum.

There was one essential element of Gladstone’s personal and political convictions that would influence every decision he would or would not make in the coming crisis: he cordially detested imperialism.

While “imperialism” has come to possess a near-obscene meaning in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, and with some just cause, in the last quarter of the 19th century it was an accepted—even expected—mode of conduct for Western European nations.

More than any other issue, imperialism defined the differences that existed between the Liberal Party under the leadership of Gladstone, and the Conservative, or Tory, Party, led in the 1870s and 1880s by Benjamin Disraeli.

Disraeli and the Tories gloried in empire, saw the expansion of Great Britain’s dominion as a sort of British version of “manifest destiny,” perhaps best expressed in the title of one of the more popular music hall ballads of the day: “We’re Getting it by Degrees.”

Unlike Disraeli, Gladstone saw no glory in empire for its own sake.

While he understood that it was incumbent upon him to defend what Britain already possessed, and he was not prepared to abandon any of the Empire’s sometimes far-flung marches, he felt no need to expand for expansion’s sake.

Gladstone’s objections to imperialism were not found on moral grounds, but on financial: no matter how much a civilizing, stabilizing, and beneficial influence British rule might have on a region—and it would be wrong as well as unfair to maintain that British rule was never any of these things-–it always cost money.

That money, Gladstone felt, could be better spent at home in Britain, improving the lives of working men and women through better education and working conditions than in simply acquiring and holding distant patches of ground, often of quite dubious value.

To him, the Sudan was just such a place.

Gladstone saw no reason for additional British conquests in Africa and wasn’t all that keen on a large British presence in Egypt.

He would have gone so far as to retire the garrison in Cairo had Baring been able to govern the country without it, though that wasn’t possible.

The extreme poverty of the Sudan meant that the cost of administering and garrisoning it would have made the Sudan a liability to Great Britain.

Glory was an intangible that Gladstone could do without, as it was expensive in both lives and treasure, and he was determined to be sparing of both.

So the Prime Minister figuratively drew the line at Wadi Halfa, where the Nile flows into Egypt, and declared that Britain’s obligations ended there.

If the Egyptian garrison and civilians in Khartoum were to be saved, it was the Egyptians’ responsibility.

Baring agreed with Gladstone that it was unwise to commit British prestige or resources to the defense of Khartoum, though for not quite the same reasons.

While Gladstone saw no reason for Great Britain to assume responsibility for the Sudan, Baring questioned the necessity for Egypt to continue to maintain it.

He frankly admitted that he saw no reason for the Khedive to maintain his rule over the unhappy land to the south, so badly had it been mismanaged in the previous half-century.

If Egypt were to defend itself, it should do so in the Valley of the Nile, at Wadi Halfa, not Khartoum.

The defense of Khartoum, as Baring saw it, would serve no purpose save the defense of the Sudan, and that country was, for all intents and purposes, already lost.

Both Gladstone and Baring perceived a genuine threat in the Mahdi’s rebellion, first to the Europeans living in Egypt, but more importantly for the Empire, to the Suez Canal.

If the rebellion spread into Egypt and a genuine Islamic revolt took hold, the Europeans would be held hostage to the Moslems mobs, and would most likely be slaughtered out of hand, undeniably a tragedy of horrific proportions.

But a closure of the canal was a possibility with frightening implications for the security of the Empire, for it would fundamentally alter the geopolitics of the day, with consequences as far away as Afghanistan, where Great Britain played a never-ending game of king-of-the-hill with Russia in defense of India, and in the Far East.

It was this threat that created an upheaval in Gladstone’s Cabinet, denying him the opportunity to consign Khartoum and the Sudan to their fates.

Everyone agreed that the Mahdi must be stopped; the question was where?

Two of the most influential members of the Cabinet, Lord Hartington, the Minister for War, and Lord Granville, the Foreign Minister, strongly favored intervention in the Sudan.

They felt that the farther from the Canal the rebellion was halted the better.

Another part of their reasoning was the aftermath of the massacre of William Hicks’ column the year before: because Hicks had been a British general, it was widely perceived in Africa and around the world that his command was composed of British troops, and that the Mahdi had handed Great Britain a galling defeat.

For reasons of prestige alone, then as now no little consideration in international relations, Hartington and Granville argued in favor of a British expeditionary force being sent up the Nile to crush the Mahdi and his ragtag army once and for all.

There was also a strong sentiment among the public in favor of such an action, and Gladstone knew he could ignore the voice of public opinion only so long without consequence.

It was at this point, in the first week of January 1884, that Gladstone, Hartington and Granville, in the manner of politicians throughout history, began formulating a political solution to what was essentially a military problem.

No one in London wanted a war, although one was looming; no one wanted to spend the money required to whip the Egyptian Army into something resembling a disciplined fighting force.

But the alternative would be to spend the money sending the British Army out to defend Egypt.

No one wanted to commit Britain to the defense of the Sudan, yet they all wanted the Mahdi kept out of Egypt.

Most of all, the government needed to appear to be doing something about the situation in the Sudan: to remain idle would be to ignore public opinion to such a degree that a reaction in the House of Commons might well bring Gladstone’s government down.

In order to accomplish these paradoxical goals Lord Granville came up with what seemed to be a workable solution.

A senior British officer of sufficient prestige and well acquainted with northern Africa would be sent out to Khartoum.

Though he would have no command authority, and carry no warrant from the government to do more than “report” on the situation there, it might well be possible for this officer to find a way to extricate the Egyptian garrison from Khartoum.

It was even conceivable that once the Mahdi knew of the presence of the Crown’s representative in the city, he would spare it, bypass it, or even bring his rebellion to a halt rather than risk rousing the ire of the British Empire.

As a solution to the problem it was elegant in its simplicity—and appalling in its stupidity.

The Mahdi was not, as Granville and Hartington, and to a lesser extent Gladstone, seemed to believe, some desert vagabond with a rabble in trail who happened to get lucky against William Hicks’ pathetic column of Egyptians.

It completely escaped their grasp that what had occurred in the Sudan was a genuinely popular uprising, given focus and direction by the Mahdi’s religious fervor, but one springing from decades of bitterness.

It also fatally misunderstood the Mahdi, for despite the fact that he was ever more readily succumbing to the physical pleasures that his succession of victories had brought, as well as becoming more and more enamored of his seeming omnipotence and self-proclaimed semi-divinity, he still in his heart of hearts believed that he was chosen by Allah to lead this cleansing tide of

jihad

against the corruption that had perverted Islam.

The Mahdi would not be turned aside by hollow threats or empty bluster—he was a man with a divine mission that would not be deflected one whit.

So, in their blind miscalculation, Granville and Hartington set about finding an officer who could carry out their impossible mission.

It was a bitterly ironic twist that the officer they found–and as fate would have it, they did not have to look very far, for even as they conferred he was in London—was the one man in the whole of the Empire with sufficient courage, skill, and charisma who could have actually carried off their fantastical scheme.

As it was, he would come closer to doing so than anyone could possibly have imagined.

His name was Gordon.

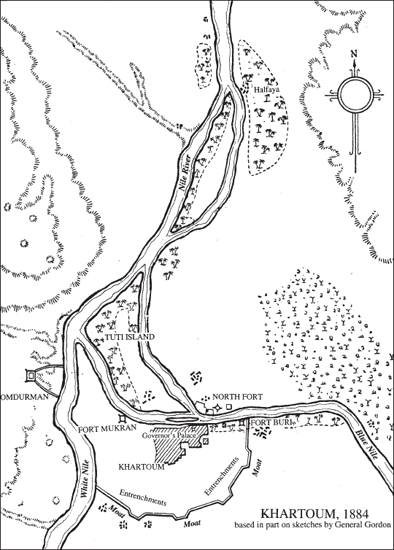

KHARTOUM IN 1884

CHAPTER 5

GORDON

In the last half of the 19th century, a time when military eccentrics of the type that a later generation would describe as “mavericks” abounded, there were few as intriguing, fascinating, exasperating, or ultimately enigmatic as Major-General Charles George Gordon.

Colorful is an inadequate adjective in describing this most unusual soldier: he could in turns be charming, imperious, baffling, flamboyant, tender, ruthless, impulsive, or calculating.

He was, in short, the embodiment of a generation’s ideal of the perfect British officer, the “very model of a modern Major-General.” Prime Minister William Gladstone, rising in Parliament, would declare of him, “He is no common man.

It is no exaggeration, in speaking of General Gordon, to say that he is a hero; it is no exaggeration to say that he is a Christian, and that in his dealings with Oriental peoples he has a genius—that he has a faculty of influence and command, brought about by moral means; for no man in this House hates the unnecessary resort to blood more than General Gordon; he has that faculty which produces effects among those wild Eastern races almost unintelligible to us Westerns.”

Gladstone’s speech touched on two facets of Gordon’s character that shone above all others: his remarkable talent as a leader of men, and his unswerving faith in his God.

His courage was unquestionable; he would place himself at the head of his troops, marching to the sound of the guns, armed with nothing more than a walking stick and his own sense of invulnerability.

When he fought his last battle, he is said to have dismissed a horde of his foes with a scornful wave of his hand, as if his sheer disdain would turn them aside.

His religious convictions were unshakeable.

He believed in a merciful, loving God and embraced the doctrines of the English evangelical church with the enthusiasm of a true disciple, and put them into practice decades before they became popular.

In particular he gave financial support to charities, taking a particular interest in establishing schools for working-class children.

He was also one of the earliest advocates of transition to native rule in the colonies of the British Empire.

Together, these traits—at once strengths and flaws—would conspire to bring Gordon to his greatest triumphs, and ultimately spell his doom.

Other books

Sabra Zoo by Mischa Hiller

Chance of a Lifetime by Jodi Thomas

A Highland Knight's Desire (A Highland Dynasty Book) by Amy Jarecki

The Worst Street in London: Foreword by Peter Ackroyd by Rule, Fiona

A Wedding in Springtime by Amanda Forester

The Gift by Portia Da Costa

Rogue (Dead Man's Ink #2) by Callie Hart

Dread Locks by Neal Shusterman

Blood in the Water by Tami Veldura

The Clone who Didn't Know (The Genehunter) by Kewin, Simon