First Jihad: Khartoum, and the Dawn of Militant Islam (22 page)

Read First Jihad: Khartoum, and the Dawn of Militant Islam Online

Authors: Daniel Allen Butler

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: HIS027130

BOOK: First Jihad: Khartoum, and the Dawn of Militant Islam

5.9Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Gordon, for his part, believed with equal fervor that he was right.

It would be immoral as well as politically irresponsible to abandon Khartoum and its people to the Mahdi.

Already the momentum behind the Mahdist rebellion was so great as a consequence of his unbroken string of victories over the Egyptians that allowing Khartoum to fall to the Arabs could carry the rebellion into Egypt, where the Egyptian peasants would almost certainly rise out of sympathy.

The consequences for Great Britain would be unthinkable: the loss of the Suez Canal, the possibility of revolt throughout the Ottoman Empire, allowing Russia an opportunity to exploit the chaos and seize Constantinople—even the specter of a Moslem uprising in India.

Those were the political consequences, as Gordon saw them, of allowing Khartoum to fall, and in truth none of them were at all improbable.

As for the moral questions, given the fate which the Mahdi had already made unambiguously clear awaited the garrison and the populace, it would be an affront to the Christianity which both Gordon and Gladstone each held dear to allow such an atrocity to take place.

It would be wrong to assert, as Churchill once did, that “If Gordon was the better man, Gladstone was incomparably the greater.” Both were good men; both were in their own way great.

What was being decided in London was whether or not Gladstone’s greatness would suffer a momentary lapse in the name of political expedience.

Yet even while the answer to the question was taking shape, events were taking the decision out of Gladstone’s hands.

The debate ground on, the motion for censure would come and be voted upon, but should the Government survive, it would find its policy dictated not by Gladstone, but by the public will.

When the vote came, the motion of censure was defeated by only twenty-eight votes–a distressingly narrow margin.

Gladstone’s government survived the confrontation, but he understood that it could not survive another.

In Cairo, Sir Evelyn Baring had been doing his best since early February to act as an intermediary between Gordon and Gladstone.

For over a month, beginning with Gordon’s arrival in Khartoum, he had been bombarded with a steady stream of telegrams from the Sudanese capital, as Gordon would conceive of new ideas for executing his instructions, sometimes as many as thirty a day.

Some were contradictory, some were far-fetched, and some, like the idea of using Zobeir Pasha as a governor-by-proxy, had considerable merit.

Baring dutifully sifted through them all, discarding the ones that were clearly unfeasible or had been overtaken by events, and sending those worth consideration on to London.

Ironically, though perhaps inevitably, Baring came to bear the brunt of Gordon’s frustration and growing animosity as his repeated demands and pleas for intervention by British troops went unanswered.

Somehow it never seemed to occur to the General that the source of his frustration was in fact Gladstone’s blunt refusal to involve the Empire any further in the Sudan.

One searches Gordon’s journals in vain for some hint of criticism or some venting of rage at the “Grand Old Man” in London.

It seems that on some level he believed that Gladstone was playing a deeper game, and wanted Gordon to stay in the Sudan as a pretext for intervention; while Gordon would appear to be forcing Gladstone’s hand, the Prime Minister could maintain that he was still opposed to imperialist adventures, but that circumstances were compelling him to act.

The real villains of the piece, as Gordon saw them, were Granville and Hartington, who had conceived of the whole Khartoum adventure in the first place.

At the same time, the caustic and sometimes searing remarks Gordon records about Baring make it clear that he regarded the British Consul-General as an accomplice to Hartington and Granville, and that Baring was doing his level best to thwart whatever constructive actions Gordon might want to take in the Sudan.

The journals are filled with Gordon’s laments about Baring’s incomprehension of the circumstances at Khartoum and his interference in how Gordon was conducting his affairs.

It was perhaps inevitable because Gordon was first, last, and always a soldier, while Baring was the embodiment of British diplomacy.

Not for Gordon the prevarication, posturing, deception, and duplicity, the endless maneuvering within moral shades of grey, which were of necessity a diplomat’s stock in trade.

His conduct in China demonstrated that for Gordon the world was simply black and white.

His was a Manicheanist Christian perspective: good vs.

evil, right vs.

wrong.

To Gordon his confrontation with the Mahdi was simple if not simplistic in nature: the Mahdi was evil, Gordon was good.

That was all he needed to know and believe, and it would be his guide throughout the eleven months of the siege.

Baring, however, had no such philosophical luxury.

With the memory of the Arabi revolt, with young Egyptian men roaming the streets of Cairo calling on the Moslems to kill the Christians within the city, still fresh in his mind, Baring knew that a Mahdist triumph at Khartoum might well trigger another uprising in Egypt, and by appearing to have defeated one of Britain’s most popular generals, the Mahdi’s myth of invincibility would gain credence throughout the Middle East.

Consequently, Baring continually forwarded London’s requests, demands, and eventually pleas to Gordon to leave the city, even if it meant abandoning the garrison and populace.

This galled Gordon, who began to suspect that it was only Baring who wanted him to leave, not realizing that Baring was passing on to London the best of Gordon’s ideas for saving the city, as well as the frequent explanations of his reasons for staying there.

The relationship between Baring and Gordon had always been somewhat stiff.

It would be wrong to say that they disliked each other; more correctly it should be said that they simply didn’t understand each other.

It was more than the broad differences in perspective and opinion that always exist between a soldier and a diplomat.

It was also more than contrast between Gordon’s deep-seated Christianity and Baring’s more pragmatic, less clearly defined view of the world.

It was the difference between a man of action and a man of patience.

Gordon was all for “doing,” for acting and reacting, for making things happen rather than letting them happen.

Baring, of course, was cautious and measured, always preferring to let events play themselves out and work the consequences to Britain’s advantage rather than try to shape them as they developed.

Gordon received a sense of this when he first met Baring in 1877 in Cairo: remarking on their introduction and the apparent coolness that immediately sprang up between them, the General observed, “When oil mixes with water, we will mix together.” It was unfortunate for Gordon that he probably never understood Baring well enough to realize that while Sir Evelyn was not a friend or an ally, he was at least sympathetic to Gordon’s aims.

The same could not be said for the man in London who had sent Gordon to Khartoum in the first place.

One of the unsolvable riddles of the fall of Khartoum is why Gordon never seemed to understand that Gladstone was playing politics with his life.

Gordon, to all appearances, never considered that Gladstone would simply abandon him in the middle of the Sudan once he chose to stay in Khartoum.

It may have been that Gordon trusted to Gladstone’s Christianity, which he regarded in many ways as robust as his own, and believed that Gladstone was prepared to stand up to the Mahdi’s rising tide of Islam.

He may even have believed that Gladstone had sent him to Khartoum in order to give the government the necessary causus belli in the Sudan.

Whichever the truth may have been, what is inescapable is Gordon’s belief that defending the city was his destiny.

His Khartoum journals put this beyond a doubt.

Save for a humorous reference or two about the shape of Gladstone’s collars and his passion for chopping wood, Gordon’s journals are empty of any telling criticism of Gladstone.

Lord Granville is rightly treated as a nonentity, while Lord Hartington is rarely mentioned.

Instead it is on Baring in Cairo that Gordon vents his displeasure.

It would prove tragic, indeed fatal to Gordon, that the two men did not understand each other better, for had they done so and worked in harmony, the story of the months and years to come may well have turned out differently.

Ironically, it was a man who Gordon had dismissed as ineffectual who ultimately forced the Government to do exactly what Gordon had hoped it would.

Lord Hartington, the Secretary of State for War, and one of the architects of the plan that had originally sent Gordon to Khartoum, came to believe that not only was the fate of the government tied to the fate of the city, but so was national honor.

He was the first within the Cabinet to finally acknowledge the obligation the government had assumed when it sent Gordon to Khartoum.

He then brought to bear all his considerable influence to compel Gladstone to send a relief expedition up the Nile.

Lord Hartington’s conscience was a powerful motivating force, for no one in all of Great Britain had a reputation for greater probity and depth of conscience than he.

So scrupulously fair and honest was the man that it was something of a national joke–an affectionate one–that whenever there was a dispute over cards at Hartington’s club, the matter was never referred to the club’s governing board, but sent to Hartington for resolution.

In public affairs, no less than in private, Lord Hartington’s decisions carried extraordinary weight.

To the vast majority of Britain’s common folk, Hartington was a man they could trust.

For all his patrician lineage—and Hartington, who was destined to eventually become the 8th Duke of Devonshire, had aristocratic roots that ran back to the Norman Conquest—he was the embodiment of what an Englishman should be.

In the fifty-one year-old Hartington, with his tall frame, thin bearded face and hawk-like nose, Britons saw those qualities which they liked to believe resided in all of them: a passion for fair play, integrity and impartiality, and above all common sense.

Never self-seeking, nervous or excited, Hartington was imbued with an unshakeable sense of duty, yet at the same time seemed to lack both ambition and imagination.

Twice he would be asked by his Sovereign to form a government and twice he would refuse.

It is likely that he was too honest to be a good Prime Minister and he knew it.

Churchill, somewhat condescendingly, would write of him, “He would never, in any circumstances, be either brilliant or subtle, or surprising, or impassioned, or profound,” and therein lay the source of his strength and his influence: whatever Hartington said or did could be counted upon to be sensible and well thought-out.

An Ansar warrior.

The patched jibba was symbolic of his service to the Mahdi, while the obsolete Schneider rifle was typical of the firearms carried by most of the Mahdi’s followers.

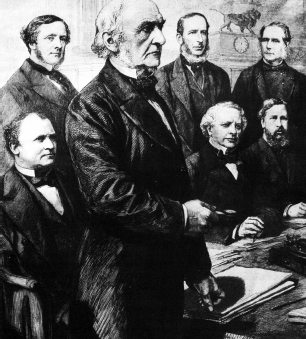

Muhammed Ahmed ibn Abdullah, the Mahdi.

While there are no known photographs of the Mahdi, this wood-cut is widely accepted as an accurate portrayal at about the time his rebellion in the Sudan began.

Other books

Surviving The Evacuation (Book 5): Reunion by Tayell, Frank

WHEN A CHILD IS BORN by Jodi Taylor

Cry Havoc by William Todd Rose

Owned By The Alphas: Part Two by Faleena Hopkins

Come Down In Time (A Time Travel Romance) by Ransom, Jennifer

No Survivors by R.L. Stine

Nice Couples Do by Joan Elizabeth Lloyd

Project 17 by Laurie Faria Stolarz

Uprising by Therrien, Jessica

Shiver by Deborah Bladon