First Jihad: Khartoum, and the Dawn of Militant Islam (23 page)

Read First Jihad: Khartoum, and the Dawn of Militant Islam Online

Authors: Daniel Allen Butler

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: HIS027130

BOOK: First Jihad: Khartoum, and the Dawn of Militant Islam

5.08Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Gladstone and his Cabinet, 1880–1885.

Seated at the far right is the Marquis of Hartington, the Minister of War; next to him is Lord Granville, the Foreign Secretary.

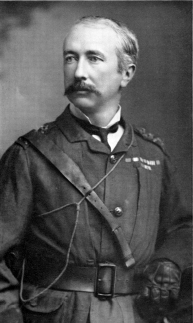

Major General Sir Charles Gordon, photographed in Cairo in 1884 before his departure for Khartoum, wearing the uniform of an Egyptian Major General.

Dervishes engaged in one of their ritual dances, the wide, sweeping movements of which gave rise to the term “Whirling Dervish.”

Dervish Warriors.

They wielded their leaf-bladed broadswords with awesome skill, and in battle they were absolutely fearless.

Colonel William Hicks, seated second from right, and his staff.

An officer of only average ability, Hicks died along with the rest of the Egyptian column he led into the Sudan to suppress the Mahdi’s rebellion in 1883.

General Sir Garnet Wolseley.

Although he was a brilliant organizer he was an unimaginative strategist, and his cautious advance of the Relief Column doomed Gordon and the city of Khartoum.

The Governor’s Palace, Gordon’s residence, in Khartoum, viewed from the Nile sometime in the 1930s.

It was from this rooftop that Gordon looked northward in vain for the British relief column.

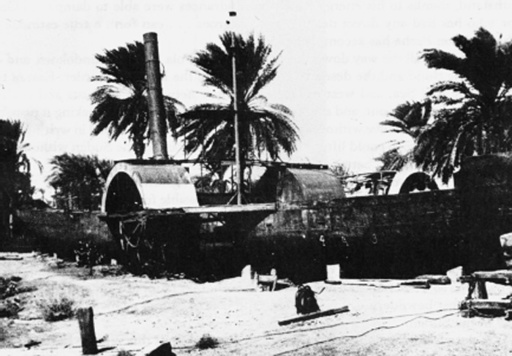

The hulk of the Nile steamer

Bordein,

which carried some of Gordon’s last messages to the outside world during the siege of Khartoum.

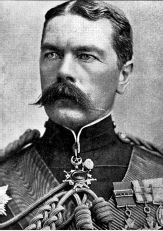

Major General Herbert Horatio Kitchener.

As a Major he had served with the Relief Column in 1885.

Eleven years later, he commanded the force which retook Khartoum and the Sudan.

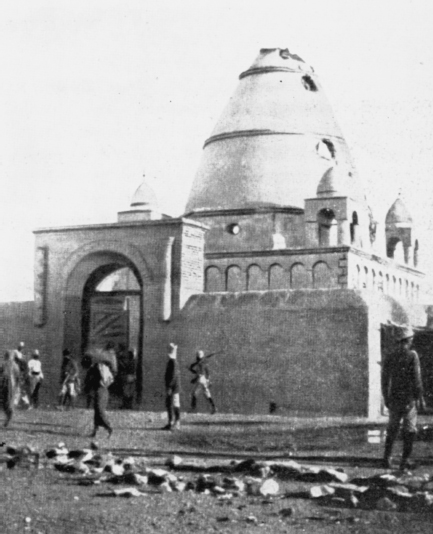

The Mahdi’s Tomb after the Battle of Omdurman.

Stray British artillery shells damaged the dome during the battle, and Kitchener plundered the tomb when he occupied the city.

Gordon’s Memorial.

Originally erected in the city of Khartoum, it now stands outside the boys’ school Gordon founded in Surrey.

One significant defect that Hartington had for certain was that he never did anything quickly.

He moved slowly, thought slowly, and acted slowly.

It was not that he was dense, but rather that he took the time to appreciate a thought or a deed completely before carrying it out.

Some observers felt that this was an impediment to his career.

Neither quick-witted like Disraeli nor fiery and powerful like Gladstone, Hartington was at a disadvantage in the cut and thrust of parliamentary debate.

Yet while speed can sometimes permit a statesman to escape unhurt from the consequences of a misjudgment or irredeemable mistake, it was the deliberateness with which Lord Hartington reached his conclusions that often allowed him to avoid disasters and mistakes in the first place.

For all of Gordon’s dedication to saving Khartoum, Baring’s integrity in carrying out his office, Gladstone’s passionate anti-imperialism, and the Mahdi’s fanaticism, the fate of the British General in the Sudanese capital would be decided by Lord Hartington.

The process by which this happened is easy to follow.

By the middle of March 1884 Hartington had become convinced that he–along with the rest of the Cabinet–had to take responsibility for Gordon’s appointment to Khartoum and the danger the General now faced.

Acknowledging that danger, his conscience would not allow him to sit idly by while Khartoum fell and Gordon died.

This led him to turn the awesome power of that conscience on the Cabinet, until they too felt compelled to take action on the General’s behalf.

When it appeared that his colleagues were vacillating, Hartington pressed his case all the harder, until the whole of the Cabinet came to agree that a relief expedition had to be authorized.

Now it was Gladstone’s turn to feel the brunt of Hartington’s moral authority.

Clinging to the shreds of his anti-imperialistic arguments and his claims that the Mahdi’s revolt was a Sudanese struggle for freedom, Gladstone resisted, prevaricated, delayed, and postponed any decision; proposal met with counter-proposal, straightforward resolutions met with subtle and complex objections.

It soon became clear to Hartington that what he was really facing was Gladstone’s inability to recognize that he had made a mistake, first in sending Gordon to Khartoum, then in refusing him military support.

The whole affair exposed Gladstone’s most glaring political vulnerability: the old man could not admit to an error in judgment.

Other books

Big Goodbye, The by Lister, Michael

magic and mayhem 01 - switching hour by peterman, robyn

Stripped by Tori St. Claire

Uncertain Allies by Mark Del Franco

The Rake by Georgeanne Hayes

The Veils of the Budapest Palace (Darke of Night Book 3) by Treanor,Marie

Lone Wolf Ripples 03 - The Fire of a Lone Wolf's Heart by Anya Byrne

A Little Bit of Truth (Little Bits) by Murphy, A. E.

Dunc and Amos on Thin Ice by Gary Paulsen

By My Hand by Maurizio de Giovanni, Antony Shugaar