Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation (13 page)

Read Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation Online

Authors: Elissa Stein,Susan Kim

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #History, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Personal Health, #Social History, #Women in History, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Basic Science, #Physiology

The Internet, being the clearinghouse of not only much useful information but also rants from the fringe, gives us this recent mature post from a mainstream men’s health Web site: “Some guys are absolutely disgusted at the mere thought of going anywhere near her vagina when it should be ‘closed for maintenance,’” and guys should explore other ways to be satisfied “until her playground’s no longer muddy.” Such sentiments eerily echo those of 1951’s The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Sex, which stated that both men and women were often queasy about female genitalia even when a woman wasn’t menstruating, “because of the wetness of the zone. They think it is messy, or that a woman is ‘dirtier’ than a man.”

All right, already; we think we’ve succeeded in making ourselves seriously depressed. It’s time for a much-needed reality check, okay?

Despite all the apparent squeamishness out there, many women and their partners in fact find sex during menstruation just ducky. Sure, one can still get pregnant in the process if not using protection, and what’s more, it might not be the best time to break out those 500-thread-count Egyptian pima sheets. Some women keep an extra set of dark sheets or a towel on hand to deal with the spillage. Others shrug and say to hell with it.

Some women also find their mojo runs a bit higher during their periods. Even the otherwise dour Illustrated Encyclopedia of Sex grudgingly admits that menstruation might have some sort of influence on a woman’s sex drive (“a nervous excitability that considerably affects their mood and conduct”), albeit not necessarily a positive one. And last but not least, a 2002 study done at Yale University indicates that women who have orgasms during menstruation are less likely to develop endometriosis. How’s that for encouraging?

Did you know that both sex and orgasms help relieve menstrual cramps? What’s more, the uterine contractions of orgasm help propel one’s flow on its journey down and out, always a good thing. And oxytocin, often called the “bonding” or “love” hormone, is routinely released during orgasm, bringing with it a much-welcome sense of calm and well-being. What could be better when one is perhaps feeling a tad bloated and achey in the first place?

So where does all this leave menstruation, sex, and religion today? We’re intrigued to report that there are people out there willing to push the envelope a little, such as those who follow Tantrism. This faith, which started in ancient India, features sex rites and ceremonies that throw traditional, male-centric, and subordinate roles for women out the window. Both male and female bodies are celebrated equally, as are fertility and sex. In fact, the highest of Tantric sexual rites calls for a menstruating woman to be an active participant.

Thousands of Jewish women are also reclaiming the mikvah—transforming it into a positive personal and spiritual experience. Whether to acknowledge a significant life change, a happy event, or a personal loss, women are connecting to the regeneration and rebirth symbolism of immersion in a completely new way, although not necessarily to the liking of the more traditionally minded in the Jewish community.

Okay, we’re not saying the world will be saved by people reinventing the mikvah or practicing Tantric sex (although the idea does intrigue). Yet sex and religion, at least as they relate to menstruation, have been extraordinarily powerful for centuries, reinforcing negative and damaging mistruths about women and their bodies that linger to this day. Making a stand for the basic rights of women may start with something as simple as questioning where such taboos come from … and beginning to eradicate those powerful religious stigmas that make menstruation such a dirty word in the first place.

SOCIETY’S ROLE

A

CCORDING TO STUDIES, ONE OUT OF EVERY TEN school-age girls in today’s sub-Sarahan Africa routinely skips school when she has her period or just drops out altogether once she hits puberty. This is due to lack of not only private facilities (and it can be traumatic enough to go change a tampon in eighth grade even with the most private bathroom in the world), but basic femcare, as well. Added up, these absences total something like 10 to 20 percent of missed school time, which puts the average African schoolgirl at a huge disadvantage for the rest of her life. As a result, in November 2007, Procter & Gamble brands Always and Tampax announced that they were teaming up with HERO, an initiative of the United Nations Association. Their five-year awareness-building program is called Protecting Futures, through which, along with improving education, nutrition, and health services, they plan to distribute free Always and Tampax products to a small network of schools. “There are lots of reasons kids miss school,” said the P&G director of the program. “Being a girl shouldn’t be one of them.”

Commercial femcare is not unlike clothing in that both share a strange relationship with the social and political movements of the day. Developments and innovations in both have not only reflected society but, like all good design, have arisen directly and organically from the needs, beliefs, and values of the times. As a result, even the lowly pad or the humblest tampon can claim to be a genuine, if unconventional, agent of change.

Here in today’s America, we tend to be downright blase about the social, political, and career opportunities available to us as women. While there may still be a glass ceiling, we only notice it because we’re finally high enough to bump against it. Nobody bats an eye at the thought of a female tennis champion, prime minister, astrophysicist, hedge fund manager, baseball ump, or lead guitarist. Women are not only capable of bringing home the bacon and frying it up in a pan, we can also marry and divorce at will, stay single and/or childless without being burned as some kind of witch, take out mortgages, own property, control our own money, pursue a Ph.D., and vote. Along the way, we can buy tampons, too. Yet a mere hundred years ago, virtually none of this was even a remote possibility.

Since its inception, the struggle for women’s rights has been and continues to be like a pendulum swinging back and forth between progress and reaction to that progress. Funnily enough, the two most important women’s movements of American history also happened to coincide with the biggest gains in menstrual management. Hard-fought gains in women’s rights came about just as advances in femcare were promising and actually creating new and unheard-of opportunities.

Conveniently, the movement for women’s rights can be broken down into three waves. “First-wave feminism” took place during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the United States and United Kingdom. It concerned itself in part with some pretty radical and wild-eyed notions: that women could, for example, own property all by themselves, have sex without being married, exercise birth control, and not be literally owned, along with their children, by their husbands and fathers like so much furniture. Mostly, however, first-wave feminism was about female suffrage—the right to vote.

Back then, there was a lot more at stake to voting rights than just being allowed to wear goofy campaign buttons, pull a lever, and then watch election returns on CNN with a sinking stomach. The underlying argument—that women were actually entitled to basic rights as individuals outside of their standing with men—became a prickly, nay, downright cranky national debate. In fact (and you may want to sit down for this part), most believed that a woman’s menstrual cycle made her inherently unstable, irresponsible, and incapable of any kind of intellectual rigor, a virtual time bomb of tears, soggy emotionalism, and hysteria.

The New York Times, the esteemed Gray Lady herself, published this opinion in 1912: “No doctor can ever lose sight of the fact that the mind of a woman is always threatened with danger from the reverberations of her physiological emergencies (i.e., menstruation). It is with such thoughts that the doctor lets his eyes rest upon the militant suffragist. He cannot shut them to the fact that there is mixed up in the woman’s movement such mental disorder, and he cannot conceal from himself the physiological emergencies which lie behind.” And the year before: “The mind of woman is so essentially different from that of man. Are you prepared to introduce sentimentalism and hysteria into the most solemn task a freeman has to execute—a task which should be approached in the same spirit in which you would approach a church—a task calling for the best powers of a mature masculine mind?”

Funnily enough, the two most important women’s movements of American history also happened to coincide with the biggest gains in menstrual management.

Early suffrage workers like Lucy Burns and Alice Paul, founders of the National Woman’s Party (NWP), didn’t have the luxury of fronting a movement from a comfy home office, armed with the Internet, an espresso machine, and some landlines. They instead held rallies, wrote pamphlets, organized parades, protested in front of the White House, chained themselves to fences, and went on hunger strikes … and as a direct result, were summarily beaten, shackled, arrested, thrown in prison, and, once there, tortured apparently for the sheer heck of it. And has one ever wondered throughout all this how these women actually handled getting their periods on top of everything else? Come to think of it, what did any woman do, prior to the advent of commercial femcare, in order to manage her monthly blood?

The answer, such as it is, will make you blanch. Up until a hundred years ago, women had to sling together their own methods of dealing with their flow any ol’ way they could—with rags, towels, or with nothing at all. All of this seriously limited their mobility, meaning it was a pretty dire time for women’s freedom, both literally and figuratively. As for the suffrage workers, almost nothing has been recorded about how they dealt with their menstrual flow—as it was, a woman’s right to vote only barely merited serious mention in the press, so one can only imagine how such august publications as the Times felt about something as essentially ignominious as blood regularly seeping from female loins.

One thing that made the problem of femcare back then so incredibly challenging, a puzzler worthy of Einstein, was the lack of underwear. Ever wonder about the illustrious history of that microfiber thong of yours? Back in the nineteenth century, there were no panties, undies, bikinis, briefs, boy shorts, nary even a set of knickers. For centuries, undergarments weren’t about hygiene or propriety, but rather artificiality, adornment, and warmth: chemises, petticoats, rib-cracking corsets, bodices.

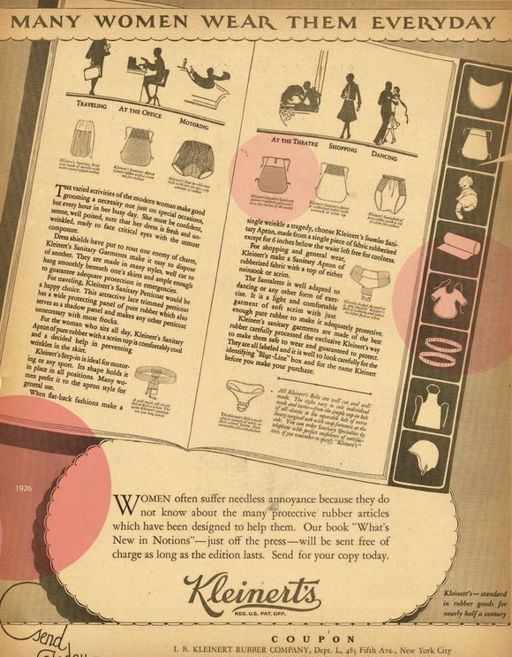

Perhaps one reason for all those petticoats and shifts was to protect one’s outer dress from blood and other stains … or perhaps we kid ourselves. After all, if one was industrious and had a little mad money, it was possible to scare up a cotton apron lined with rubber, which presumably kept blood from seeping into the seat of one’s dress. There were also bloomers with rubber panels at the bottom available; but all of these were relative rarities, and due to their cost, effectively out of range for most women. No, most had to resort to stuffing between their legs or up their vaginas those materials they could get for free: rags, pieces of sheepskin, leaves, moss, or nothing at all.

From Harry Finley, founder of the online Museum of Menstruation, comes this translation from Friedrich Eduard Bilz’s Das Neue Naturheilverfahren (The New Natural Healing), published in the late nineteenth century: “Many women … place nothing in that region [to absorb menses] and so in addition to the outer sex organs, underwear, sheets and bed covers, the lower belly and thighs are stiffened with dried blood … and finally because of the widespread prejudice against frequent washing and changing of clothes during this time, some women, even those of the better classes, are often filthy to an almost unbelievable degree.” Gives one a whole new way of looking at Scarlett O’Hara and Marie Antoinette, doesn’t it?

Women could also depend on the good ol’terra firma, the ground itself. Female factory workers would often work standing up, sans underwear and knee-deep in straw into which they freely bled. The workstation, much like a stall full of farm animals, would be mucked out when the conditions became unbearably filthy.