Folklore of Yorkshire (24 page)

Read Folklore of Yorkshire Online

Authors: Kai Roberts

Although Yorkshire in not abundant is natural lakes, there are a few examples and, perhaps inevitably, their origins have been thoroughly mythologised by generations of country folk. Yet, the narratives which have accreted around them differ quite considerably from the motifs associated with rivers. For, whilst the latter display distinctly animistic – some might say ‘pagan’ – characteristics, Yorkshire’s lake legends embody a firmly monotheistic milieu, communicating orthodox Christian theology regarding almsgiving and divine judgement. Like many traditions connected with the Devil (

See

Chapter Six), these stories seem to have arisen to provide local congregations with concrete examples of God’s power, by taking a common migratory legend and relocating it to a setting familiar to the audience.

The most famous example concerns Semerwater, the largest natural lake in North Yorkshire and the second largest in the county as a whole. It nestles in the secluded confines of Raydale, a tributary valley of Wensleydale and is surely one of the most picturesque spots in that region. The legend tells that a prosperous settlement once stood where Semerwater lies today, and its wealth was such that the people of the town had grown proud and decadent. One day, an impoverished and elderly vagrant – some say a pious hermit – stumbled upon this community and went from door to door humbly asking for some provisions to help him on his way. But, such was the arrogance of the townsfolk, they refused to provide the old man with even a morsel of food and he was turned away from every house he visited.

At length, after he had been snubbed at every dwelling in the town, he came across a much less affluent residence high on the flanks of the surrounding valley. It was occupied by a poor shepherd and his wife, but despite their own hardship, they insisted the beggar partake in their meal and offered him shelter overnight. Thus, the following morning, before he travelled on, the old man looked down on the community that had treated him so poorly, raised his arms to the heavens and declaimed, ‘Semerwater rise, Semerwater sink and swallow all the town, save yon li’l house where they gave me food and drink!’ Sure enough, a deluge rose to consume the uncharitable town; but whilst it submerged the houses of all those who had turned the hermit away, the waters stopped just short of the cottage where he had found hospitality at last.

A similar tale is told of Gormire, a small body of water which lies beneath Whitestone Cliff on the edge of the Hambleton Hills. Gormire is an unusual lake in that no streams or rivers feed or drain it; rather it is a glacial feature sustained by a spring alone, but doubtless this curious composition helped foster the notion that it was bottomless. Local legend claims that it too was once the site of a wealthy town which was inundated following a terrible earthquake; however, the story is less clear on the connection between the pride of its inhabitants and its watery fate. Nonetheless, it was long believed that ruined buildings lay beneath the surface of Gormire and could be seen glinting in the depths when the waters were especially clear.

Semerwater in Raydale, beneath which lies a sunken town. (Kai Roberts)

The sunken city is a common motif across the world and has been throughout the ages. As early as the fourth century

bc

, the Ancient Greek philosopher, Plato, implied that the legendary city of Atlantis was drowned by the gods as punishment for its leaders’ hubris, and the trope also appears extensively in Celtic mythology – most pointedly in the Breton legend of Ys. Perhaps more significantly, the theme has parallels with the Judaeo-Christian tradition of the Great Flood, which the Book of Genesis claims God sent to express his displeasure with the sinfulness of mankind. The lesson of the deity’s retribution against communities who prodigiously sinned or failed to exhibit virtues such as charity, was doubtless one that clergy, both Catholic and Protestant, wished to instil in their flock and by attaching this moral to a local landmark, sought to bring it closer to home.

Whilst Yorkshire may not have many natural lakes, it is rather more abundant in springs; especially those which have been dedicated to some patron saint and dubbed ‘holy wells’. Indeed, according to one reckoning, the county has the highest density of such wells in England outside Cornwall, a region widely considered to be the home of the holy well. The precise definition of a ‘holy well’ is contested: some authorities use the title to refer solely to those wells which have been consecrated by the Christian Church, whilst other sources employ the term rather more loosely, applying it to any well that possesses some historic or cultural significance. In the interests of avoiding confusion, this chapter will go on to discuss the latter category, but it will reserve the title ‘holy well’ for the former alone.

There is also much controversy surrounding the provenance of well worship. For many generations it was popular to assume that holy wells were a direct survival from the animistic pre-Christian religions of the British Isles, and that a continuous tradition of veneration from that period could be identified at a number of examples. There are certainly understandable grounds on which to believe this: there is extensive evidence of votive offerings being deposited in water sources during the Iron Age and Romano-British period, and superficially, the medieval holy well tradition has much in common with such ancient practice. On the other hand, the rationale of the assumption depended greatly on the early folkloric hypothesis of ‘survivals’, which has long been discredited – at least as far as pagan survivals are concerned.

There are two substantial obstacles to supposing any demonstrable continuity of tradition in well worship from the pre-Christian period. Firstly, between the Romano-British period and the early Middle Ages, the Dark Ages intervenes. During this time, no written records exist to document the status of such belief through those centuries, and the archaeological record remains conspicuously silent on the matter. Secondly, the historical record suggests the pattern of use and abandonment of holy wells is so dynamic – even within the Middle Ages, let alone after the Reformation – that it would be quite remarkable if a tradition had endured for such a lengthy period of time. Therefore, it is more realistic to suggest that whilst Iron-Age Celts and medieval Christians may both have worshipped at wells, they probably worshipped at

different

wells. Very little evidence of the former survives and the latter took place firmly within the context of orthodox Christianity.

In his study of holy wells, folklorist Jeremy Harte suggests that those springs known simply as ‘Holywell’ may represent the earliest examples of sacred springs in the Christian tradition, in many cases pre-dating the Norman Conquest. He bases this conclusion on the extent to which these names are embedded in the landscape, in toponyms or family names such as Halliwell. Harte goes on to suggest that the distribution pattern of such wells – concentrated primarily in areas which would have been classed as ‘waste’ in the Domesday Book, but not too far from the periphery of civilisation – indicates that they were probably originally associated with hermits, and other mendicant holy men, in the period before many permanent churches were established. It is perhaps consistent then that springs baldly titled ‘Holywell’ are amongst the most ubiquitous in Yorkshire, especially the West Riding – for example, Halliwell Syke or Holywell Green, both in the vicinity of Halifax.

The second wave seems to have been those wells dedicated to native saints, of which there is an abundance in Yorkshire. It is with these early dedications that the reputation of holy wells for healing first emerged. According to Catholic doctrine, the souls of saints passed immediately into the presence of God and so could function as intercessors, who would communicate a supplicant’s prayer to the Almighty. However, for the prayer to be more effective, it is desirable to be in close proximity to the saint’s remaining traces on earth. It was through such belief that the medieval cult of relics flourished, to the point where almost every cathedral and monastery in the Middle Ages preserved bones, which they claimed were those of some beatified patron.

Hordes of pilgrims flocked to offer prayers to saintly relics and such was the demand for this service, that people began to consider that it was not just the mortal remains of saints that were efficacious; maybe the places and objects they had consecrated during their lifetime were similarly potent? As such, wells from which they had drunk and supposedly blessed came to act as substitute relics. It is true that such practices were regarded with contempt by some ecclesiastics, but their objections were not so much due to fear of paganism; rather, they were disturbed that they could not control and profit from the worship taking place at these sites. Their objections were about authority rather than theology. Conversely, there is evidence to suggest other churchmen not only tolerated well worship, but actually approved it.

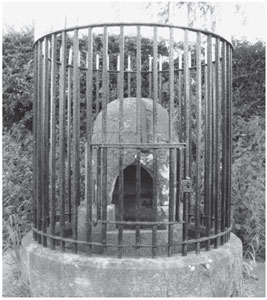

St John’s Well at Harpham, where St John of Beverley performed miracles. (Kai Roberts)

However, much as saints’ bones were easily faked, so were their wells. The only examples in Yorkshire which have a strong historical connection with their patrons are those dedicated to St Cedd and St Chadd at Lastingham, the former location of a monastery founded by those two clerics in the seventh century. However, whilst a number of wells around Whitby are dedicated to St Hilda, who established the abbey in the town during the same period, the traditions are so vague as to leave considerable room for doubt. Lady Hilda is supposed to have had a retreat near the wells dedicated to her at Hindwell and Aislaby, and often supped from Abbey Well at Hawsker, but there is no evidence to corroborate any of these traditions. It is also instructive that Christianity almost entirely died out around Whitby between the Viking invasion of

AD

867 and its Norman restoration in 1078, and it is doubtful the name of her well could have survived two centuries of pagan Danish occupation.

Other notable examples of wells dedicated to indigenous saints in Yorkshire are equally suspect. St John’s Well at Harpham is dedicated to St John of Beverley and the village claims to be the birthplace of the saint; unfortunately, contemporary sources make no reference to this fact and the tradition is not recorded before the sixteenth century. The long-lost St Robert’s Well at Knaresborough rose on land close to St Robert’s Cave, where the twelfth-century hermit is reputed to have lived, but there is evidence to suggest that it was an earlier Holywell rededicated to the local saint. Meanwhile, despite his well’s popularity in the Middle Ages, there is no evidence to suggest that St Mungo ever visited Copgove; nor, for that matter, that St Augustine once preached beside St Austin’s Well at Drewton and baptised new converts in its waters.

As the Middle Ages wore on, wells were increasingly dedicated to universal saints. In some cases, the dedication may have taken place as the result of a vision of the saint enjoyed by some rustic at that spot, much as shrines continue to spring up across the Roman Catholic world today. In other instances, the dedication may imply not that the well was considered sacred in itself, but simply that it provided the water supply for a nearby chapel. Lady Wells – dedicated to Our Lady, the Blessed Virgin Mary – were particularly common during this period, as the mother of Christ was considered to be a universal intercessor and proximity to her mortal traces was not necessary for prayers to her to be effective. In Yorkshire, examples are recorded at Hartshead, Brayton, Roche Abbey, Catwick and Threshfield to name but a few.

Wells dedicated to St Helen were also common in the late Middle Ages, especially in Yorkshire, with a famous example surviving at Eshton, near Gargrave, which is still venerated today. Indeed, some commentators have regarded St Helen as disproportionately attached to wells – her name is the most common dedication for holy wells but only twentieth for church dedications – and used this fact to suggest that this is a corrupt remembrance of the well’s previous connection with some pre-Christian female water deity. However, St Helen may have had stronger links with Yorkshire than any pagan goddess. She was the mother of the Roman emperor, Constantine the Great, who Christianised the Roman Empire under her influence. As Constantine’s father died in York, and it was from that city his own succession to emperor was proclaimed, a local medieval tradition held that Helen was a native of the area and this may have much to do with her association with holy wells in the county.