Folklore of Yorkshire (32 page)

Read Folklore of Yorkshire Online

Authors: Kai Roberts

St Mark’s Eve fell on 24 April, and until rationality prevailed in the late nineteenth century, it was another favourite night for divinatory customs. Readings were taken from impressions created by sifting the ash in the hearth (ash-riddling) or the chaff on the barn floor (chaff-riddling). It was also the designated night for a particularly macabre custom known as ‘porch-watching’. Across Yorkshire, especially in rural areas, people believed that if an individual kept nocturnal watch in the church porch on St Mark’s Eve for three years in a row, on the third vigil they would witness the wraiths of all those who were to die in the parish during the following year process down the corpse road and into the church.

There were many attendant superstitions which varied from place to place, including the belief that anybody who fell asleep whilst porch-watching would themselves die, and that whoever watches the porch once must do so for their whole lifetime. The tradition was a source of dread to many and it was widely exploited by the unscrupulous. A woman named Old Peg Doo used to watch the porch of the Priory Church at Bridlington every year, and charge her neighbours to reveal what she had witnessed. Although veteran porch-watchers were often shunned by the community, it was very easy for them to use their position for malicious ends. It was rumoured that for some people who heard that their wraith had been seen entering the church on St Mark’s Eve, it became a self-fulfilling prophecy as they were driven into such a state of anxiety that their death soon followed.

The last day of April, ‘May Eve’, was marked in Yorkshire as one of the first two ‘Mischief Nights’ of the year, a time of misrule during which gangs of youths would play a variety of pranks on their unfortunate neighbours, under the illusion the date gave them protection from the law. Typical mischief included everything from simple tricks, such as leading animals astray, securing doors from the outside and removing gates from their hinges, to more elaborate schemes like suspending a needle next to a window to create a persistent and elusive tapping sound, or boarding up the windows to cause the residents to oversleep. As one commentator remarked, ‘The first of April is the Fool’s day and the last day of that month is the Devil’s.’

May Day itself was widely celebrated in England during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and whilst it was banned during the Commonwealth, festivities were resurrected for a period following the Restoration and again in corrupted form during the nineteenth century, according to the Victorian fashion for a romanticised ‘Merrie England’. In its original form, the day was known as a riotous occasion and involved a variety of universal customs, such as maypole dancing and ‘bringing in the May’, which would see young folk go out into the surrounding countryside to collect foliage with which to decorate the village.

May Day festivities were particularly despised by Puritan reformers during the seventeenth century, who regarded such practices as both pagan and licentious. The nonconformist firebrand and inveterate diarist, Reverend Oliver Heywood, records that around 1630, the vicar of Halifax preached virulently against May Day customs and even attempted to prevent the erection of a maypole, leading to great unrest in the town. Of course, the celebration was thoroughly stamped out by the Commonwealth and whilst a revival followed the Restoration, the traditions gradually changed in form, so that by the nineteenth century, ‘bringing in the May’ had evolved into more innocent practices such as garlanding, a children’s visiting custom. In Yorkshire, a little of the old lustiness endured and young men traditionally left foliage on the doorsteps of any girl they wished to flatter.

One of the most archetypal motifs associated with May Day is the maypole, a central feature of both the early festivities and the Victorian revival. During the nineteenth century, it was so significant that a number of villages in Yorkshire had a permanent maypole – only two survive in the county, but inevitably May Day celebrations remain vibrant in these places. Gawthorpe, near Wakefield, is one such example and their annual pageant features a horseback procession, which parades to the neighbouring town of Ossett and back before the May Queen is crowned beneath the maypole. The current pole is a former pylon donated by Yorkshire Electricity Board and winched into place by crane in 1986.

However, the more famous maypole at Barwick-in-Elmet, near Leeds, is replaced every three years by traditional methods – ladders, rope and human labour. The raising ceremony originally took place on Whit Tuesday, but has now been fixed to Spring Bank Holiday and the event has become more significant than May Day itself. By custom, work begins at 6 p.m. and takes over 100 people at least three hours to complete, during which their exertions are accompanied by a band parade and Morris dancing. Once the maypole is in place, four garlands are hung halfway up and a weather vane in the shape of a fox is fixed to the top. It is said that anybody who is struck by the pole during its erection will be left simple-minded for the remainder of their days, and the phrase ‘knocked at Barwick’ was once a local idiom for those considered ‘backwards’.

The maypole at Barwick-in-Elmet. (Kai Roberts)

Whilst the sanitised post-Restoration May Day celebrations lost their reputation for public disorder, still some unruliness remained and maypole theft became a common manifestation of rivalry between neighbouring communities. The Barwick maypole was removed twice, first by Garforth in 1829 and again by Aberford in 1907, whilst the Gawthorpe pole was stolen by Chickenley in 1850 and not replaced until 1875. A local, undated narrative from Wharfedale records that when the Burnsall maypole was purloined by a team of cobblers from Thorpe, a team of villagers were sent to retrieve it and a fight broke out; a similar confrontation is recorded between the young men of Brighouse and Rastrick in West Yorkshire, around 1785.

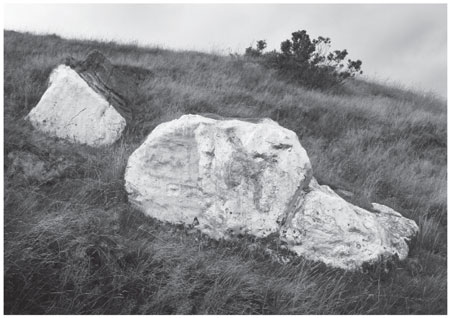

The White Rock above Luddenden Dene, repainted ever May Day morn. (Kai Roberts)

Another particularly curious May Day custom still endures in Calderdale, with no precedent elsewhere in England. First recorded in 1890, a rock on the hillside above the Cat i’ th’ Well pub, between the villages of Saltonstall and Wainstalls, is painted white every May Day morning. Nobody seems to know who performs the duty or why it originated, although a number of local tales surround the custom. In some narratives, it marks the location of buried treasure, whilst in others it is painted by the Devil himself. However, the proximity of St Catherine’s Well at Saltonstall (which gave its name in a corrupted form to the nearby pub) suggests it may originally have been connected with Spaw Sunday (

See

Chapter Ten).

The Feast of the Ascension took place forty days after Easter Sunday and whilst this was primarily a liturgical observance, the preceding three days were known as ‘Rogationtide’. During this period, a tradition called ‘Beating the Bounds’ was performed, whereby the boundaries of the parish were perambulated by civic and ecclesiastic officials alongside local residents. In the days before accurate cartography, the purpose of this custom was to fix these borders in the minds of the populace and thereby reduce the risk of future disputes. Although the function was primarily an administrative one, it had become entangled with an earlier religious procession which had once taken place on the Feast of the Ascension, and so the clergy remained actively involved in the tradition, often preaching a sermon at significant landmarks.

Young boys were also taken on these perambulations, and a variety of techniques were employed to ensure they accurately preserved the knowledge for future generations. In some parishes such as Beverley, the carrot was preferred over the stick, and money, nuts and oranges were thrown out at points which needed committing to memory. At Whitby, laces, pins and biscuits were distributed, whilst one point along the boundary was marked by the Battering Stone – a large mass of whinstone which the boys would pelt with rocks. Any boy who chipped the stone would be rewarded with a guinea from the parish coffers. There was a boundary marker at Flaxton, in Ryedale, known as the Rambleations Stone, from the top of which bread was thrown into the crowd. However, after this custom resulted in riots on several occasions, the practice was discontinued and the stone destroyed.

Some parishes preferred more austere methods of guaranteeing the boys retained a memory of the boundaries. In the Forest of Galtres, boys were ‘bumped’ at regular stations, whilst in other places they were thrown in a ditch or even whipped. In the city of York, this practice was inverted and local boys would whip the parish clerk with bundles of sedge as he stopped to record details. Also perhaps the most bizarre convention associated with ‘Beating the Bounds’ took place near York, at Water Fulford. Here, at one station along the route, a chicken was set loose and chased by the boys. Whoever caught the bird was rewarded with five shillings, whilst the poor chicken was decapitated and its severed head placed on top of a post marking the boundary!

The practice of Beating the Bounds mostly died out once its civic and legal function was no longer necessary, although its spirit is preserved in the parish boundary walks which take place in some areas at Whitsun. A Rogationtide tradition which still endures, however, is the Whitby Penny Hedge. The hedge is constructed on the shore of the town at 9 a.m. on Ascension Eve, after which a horn is blown to mark that the obligation is complete. The hedge is woven from sticks of hazel and willow, using only a knife of ‘a penny price’, and it must be strong enough to withstand three tides.

A local legend claims that the tradition started during the twelfth century, when several men murdered a hermit who had given shelter to a boar they were hunting. It is said that the hermit gave instructions for the erection of the Penny Hedge with his dying breath, to be undertaken as a penance to atone for their sin. However, there is no evidence to support this narrative and the ritual actually seems to be a remembrance of an early medieval land-tenure custom, whereby tenants of Whitby Abbey were expected to maintain something called the ‘Horngarth’ or else their lands would be forfeit. The precise purpose of the Horngarth has been forgotten, although the name suggests it was probably an enclosure for the abbey’s cattle.

As in all counties of England, Whitsuntide in Yorkshire was a time for fairs and feasting as the climate had warmed sufficiently by this time to allow outdoor gatherings. In the fifteenth and sixteenth century, Whitsun was the traditional occasion for the May Games, which the Victorians later incorporated into their revived May Day celebrations. These typically involved the election of a King and Queen of Summer, Robin Hood plays, feats of sportsmanship and morris dancing. In later centuries, the more unique custom of ‘Chalk Back Neet’ was recorded around Bridlington, when local boys and girls would gather on the church green armed with a stick of chalk and attempt to mark each others’ backs.

Royal Oak, or Oak Apple, Day was celebrated on 29 May from 1661, to commemorate the Restoration of Charles II to the throne following the Commonwealth. Whilst most Royal Oak Day traditions in Yorkshire seem to have died out by the mid-twentieth century, it was once tradition to deck public buildings with oak and for men to wear oaken twigs in their caps. Anybody who did not display such an adornment was pelted with rotten eggs or rubbed with nettles. In some villages, such as Great Ayrton in North Yorkshire, it was also customary for children to lock their teacher out of the school, whilst they chanted:

It’s Royal Oak Day

It’s the 29th of May

If you don’t give us a holiday

We’ll all run away!

Midsummer fires – which many scholars now regard as one of the few truly pre-Christian survivals in the ritual year – were recorded on the eve of the summer solstice in both North and East Yorkshire as late as the nineteenth century. Traditionally, the bones of dead animals were burnt (known as a ‘bone-fire’, from which some authorities believe the word ‘bonfire’ is derived) and spectators were expected to leap through the flames. The superstitious supposed this ritual to purify the community, along with their crops and livestock, protecting them from the various diseases and blights which were more virulent during the hot summer months.