Folklore of Yorkshire (30 page)

Read Folklore of Yorkshire Online

Authors: Kai Roberts

Robin Hood’s Grave at Kirklees. (John Billingsley)

Upon their arrival at Kirklees, Robin sends Little John to wait for him nearby and allows the prioress to lead him to an upstairs room and open his vein. However, true to Will Scarlett’s warning, treachery is afoot. Robin’s faithless cousin locks him in the chamber and leaves him to bleed out, both for the wrong the outlaw has done to the Church and to appease her lover, Roger of Doncaster. After the hero has suffered substantial blood loss, he is confronted by Roger and a fight ensues, but even in his weakened state, Robin proves a formidable opponent and slays the villain with a knife to the throat. The prioress retreats and with the last of his strength, Robin blows his horn to summon Little John.

Robin’s faithful companion arrives, breaking down doors in his wake, and begs his master to let him burn the nunnery to the ground. Robin refuses this request, stating that he has never harmed a woman and would not allow harm to come to any now. He merely asks that Little John hear his final confession, and then bury his body beside the highway nearby, with his sword at his head, his arrows by his side and his bow at his feet. In later versions of the ballad, Robin chooses the exact site of his grave by loosing a final arrow from the window of the priory and instructing Little John to inter him where it lands. However, whilst this has become the defining image of the outlaw’s demise, it does not appear in the original sources and appears to be a Romantic embellishment of the eighteenth century.

Contrary to popular belief, Kirklees is the only site to have been consistently associated with Robin Hood’s death since the Middle Ages. Perhaps more remarkably, a monument purporting to be ‘Robin Hood’s Grave’ still exists on land that once belonged to Kirkless Priory. Some commentators have dismissed this site as a gentrified folly, but whilst the grave was enclosed during the eighteenth century to protect it from vandals and a mock epitaph erected alongside it, the gravestone itself shows evidence of being much older. Furthermore, the earliest independent textual reference to the site dates from 1536 – prior to the dissolution of the priory – whilst supporting references continue throughout the sixteenth century. Although the exact provenance of the monument remains a mystery, its relative antiquity cannot be disputed.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the grave has attracted further folklore over the years. In the eighteenth century, local navvies believed that chippings from the stone offered protection from toothache – one of the main factors in the grave’s regrettable depredation. More eerily, in 1730, the historian Thomas Gent recorded that a local knight had not long ago removed the tombstone to use for a hearth in his great hall. However, each morning he rose to find that it had been ‘turned aside’ by some mysterious force, compelling him to return it to its proper place. Significantly, it required only half the number of animals to drag it back than it had taken to take it away. Both these traditions are common migratory legends, frequently associated with ancient monuments, from prehistoric megaliths to medieval memorials.

All the preceding stories were taken from ballads, and the advent of the printing press formalised and preserved such oral narratives, which may have extended far back into the Middle Ages. However, as the legend grew in popularity during the sixteenth century, a panoply of apocryphal local traditions began to emerge, the origins of which remain controversial. Some may represent lore as old as the ballads themselves, whilst others were probably later inventions inspired by the circulation of those ballads. As J.C. Holt observes, ‘There are two obvious causes of the proliferation … The first was psychological: those who told or listened to the stories tried to add to their realism by transferring the hero’s name to familiar places in the immediate locality. The second was commercial: innkeepers and other could attract custom by claiming that “Robin Hood was here”.’

One of the most oft-repeated examples of these apocryphal traditions is that Robin was born at Loxley, near Sheffield. The belief was first noted in the early seventeenth century in an anonymously written and undated prose chronicle of the outlaw’s life. known as the Sloane Manuscript and by the noted antiquary Roger Dodsworth, writing in 1620. Meanwhile, a land survey of 1637 records the ruins of a house at Little Haggas Croft in which the outlaw was supposed to have been born, and which could be seen until 1884. The Loxley legend further maintains that the young Robin was forced into life as an outlaw after he killed his stepfather with a scythe, whilst they were working land at Loxley Chase Farm. He then spent several years hiding out in a cave on Loxley Edge, before he was forced to flee the area altogether.

Robin Hood’s Bay, where the legendary outlaw kept a fishing boat. (Phil Roper)

Another location irrevocably associated with the outlaw – this time by virtue of its name – is the picturesque North Yorkshire fishing village, Robin Hood’s Bay. The settlement was first recorded under that title by John Leland in 1536, and two legends account for its nomenclature. One asserts that Robin loosed an arrow from Stoupe Brow and vowed to build a town wherever it landed – perhaps the haven he swore to found in ‘Robin Hood’s Fishing’. The second version reports that Robin’s notoriety grew so great that the king sent a great force of soldiers from London to detain him, forcing the outlaw to take refuge on the moors near Whitby. Whilst in the area, he moored a boat at the inlet where Robin Hood’s Bay now stands, so that he could escape to sea if necessary and often took it out fishing to pass his days in hiding.

A related legend claims that during this period, the abbot of Whitby invited Robin and Little John to dine with him at the abbey. Whilst they were enjoying his hospitality, the abbot requested a demonstration of their famed archery skill and so the pair ascended to the roof of the building where they each loosed an arrow in the direction of Hawsker. The arrows fell a mile away near Whitby-Laithes, one at each side of the road and Little John’s some 100 feet further than Robin’s. The abbot was reputedly so impressed that he erected a stone pillar where each arrow landed to commemorate the feat, and whilst the original pillars are no more, the fields in which the arrows supposedly came to ground are still marked as Robin Hood and Little John Close.

Robin Hood toponyms such as these abound throughout Yorkshire. The earliest recorded example is Robin Hood’s Stone, mentioned in a cartulary of Monk Bretton Priory, dated 1422. The exact location of the stone has been lost, but it was appropriately somewhere in Barnsdale. Some scholars have suggested it was close to the site of Robin Hood’s Well, which sat beside the Great North Road a short distance south-east of Barnsdale Bar. The well was first recorded by Roger Dodsworth in 1622 and it was the site of a brisk trade for many hundreds of years. Today, however, the spring itself is lost beneath the dual-carriageway of the A1; all that remains is the well house, designed by the illustrious Sir John Vanbrugh

c

. 1720, and now relocated to the side of the road.

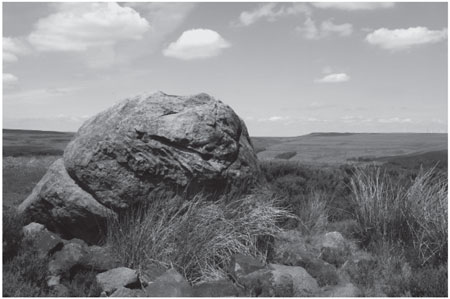

Another Robin Hood’s Well could once be found on Stanbury Moor near Haworth, accompanied by Little John’s Well and Will Scarlett’s Well nearby. Although they were practically lost by the time their tradition was recorded in 1899, local legend claimed that the outlaws once drank from these springs. Indeed, if such lore is to be believed, Robin and his men spent a lot of time in this tract of West Yorkshire. Not far away at Rivock Edge, above Keighley, there is a vast boulder known as Robin Hood’s Stone beneath which he supposedly slept, whilst similar stories are told of an earthfast boulder known as Robin Hood’s Chair and a natural rock-shelter called Robin Hood’s House, both at Baildon.

Robin’s name seems to have attached itself to a number of monoliths in Yorkshire, both natural and man-made. In some cases, he merely visited the feature but in others, he is responsible for its very existence in the landscape. As the Halifax historian, Reverend John Watson, noted in 1775, ‘The country people here attribute everything of the marvellous kind to Robin Hood.’ In these stories, Robin takes on the characteristics of a giant – as if his stature has grown to match the magnitude of his deeds – and doubtless his name was transposed over much older legends concerning the deeds of giants, whose titles are now long forgotten. It is a role adopted by King Arthur in other counties across Britain, but in Yorkshire it belongs exclusively to Robin.

Robin Hood’s Penny Stone at Wainstalls near Halifax was one such example. This large natural boulder topped by a rocking stone was broken up for building material in the nineteenth century, but prior to that locals claimed Robin Hood once ‘used this stone to pitch with at a mark for his amusement.’ There is another boulder known as Robin Hood’s Penny Stone just over a mile away on Midgley Moor which still survives today. Meanwhile, on the opposite side of the Calder Valley, there was once a standing stone known as Sowerby Lad which Robin was supposed ‘to have thrown … off an adjoining hill with a spade as he was digging.’ Sadly, this stone has also been destroyed.

A little further away atop Blackstone Edge, on the very border of Yorkshire with Lancashire, there is a rock formation called Robin Hood’s Bed. The outlaw is supposed to have slept here and used it as a lookout to observe movement on the ancient highway below. In his gigantic guise, he took one of the many boulders strewn about that place and flung it across the border, where it came to rest 6 miles away on Monstone Edge, and acquired the name Robin Hood’s Quoit. The Quoit was in fact a prehistoric burial cairn, and this connection between the outlaw and megaliths is another common theme. A row of tumuli dubbed ‘Robin Hood’s Butts’ near Robin Hood’s Bay were supposedly set up by the outlaw for target practice, and the story of the arrows fired from Whitby Abbey may have been a back-formation to account for the names of two ancient standing stones.

Robin Hood’s Pennystone on Midgley Moor, hurled by the legendary outlaw? (Kai Roberts)

Traditions such as these illustrate the difficulties with a purely historical conception of Robin Hood. Although many of his legends take place in a more recognisably historical milieu than those of King Arthur, Robin represents a similarly mythic figure in that the narratives associated with him primarily express the worldviews of communities across time and space, the character acting as a concept onto which humans project their dominant concerns. As a result, to some he is an outlaw, whilst to others he is a giant. What is certain is that he will never be a single, identifiable figure and nor should we wish him to be. Like so many folkloric entities mentioned in this book, he is fundamentally liminal and ambiguous; a shape-shifting trickster who will forever re-emerge in different guises according to the needs of those who imagine him.

C

ALENDAR

C

USTOMS

AND

THE

R

ITUAL

Y

EAR

![]()

I

n the popular imagination, calendar customs are regarded as one of the most characteristic manifestations of ‘folklore’ in the modern world. Traditions such as Morris dancing are perceived as an archetypal expression of Britain’s enduring folk heritage; an almost immemorial practice which represents the last lingering influence of a distant and idealised past. Yet such a perspective fails to appreciate the malleable and dynamic nature of such customs. They are not rigid inheritances from a previous age and whilst some continuity with earlier generations inheres, they often say as much about the contemporary context in which they are performed as any historical era. Traditions die, and others are created with surprising regularity, whilst those that persist are constantly reinvented to reflect changing demographics and new cultural ideologies.