Footloose Scot (21 page)

Authors: Jim Glendinning

What made the long hours tolerable were the guests. There is something about Bed & Breakfast guests which sets them apart from general tourists. In five years I had no disagreeable visitors, nothing stolen or damaged and only two bad checks. If I was out I left a note and people checked themselves in. The front door was never locked.

I had repeat visitors who came every year, often for Alpine's main events like the Cowboy Poetry Gathering, Intercollegiate Rodeo or Art Walk. What was rewarding was to see first-time visitors, who had perhaps driven 570 miles from Houston, starting to relax after a couple of days. The problem was that, having allowed only two nights, they then had to leave. But it was good to hear them say, after a satisfying breakfast, that they would come back. And many did.

The guests were mainly couples in their middle years. When The Corner House got mentioned in guidebooks and magazines we attracted a more general clientele, including overseas visitors.

Texas Highways

magazine did a feature on Alpine which included a picture of me standing outside the house, under the Scottish flag, wearing my kilt. Moon Publications guidebook "

Texas"

gave The Corner House a full paragraph plus a photograph.

The maximum capacity of guests after some improvements in the house was 11 persons, including two beds in the basement for budget travelers. To keep the rooms full I offered a discount to residents of Terlingua. I was always curious about people who lived in the ghost town of Terlingua, 80 miles south of Alpine, close to the border with Mexico. They had the reputation of being oddballs, artists and writers, escapees from some prior unpleasant history, PhDs and more generally just folks who wanted to live far from rules and regulations in the quiet and beauty of the desert. Some lived extremely simply, hauling their own water and without air-conditioning. The ones who stayed during the summer months were considered the real thing.

Sometimes they came to Alpine to shop or for medical attention. One Terlingua man turned up one day and asked if there was a discount. I said yes, and told him what it was. He had to stay overnight, so he accepted. He mentioned that he always got a headache when he came to Alpine. I assumed it might be because of the change in elevation since Alpine is 2,500 feet high than Terlingua. But he told me that it was because of the heavy traffic passing along US 90 which runs through Alpine. To me the relatively small amount of traffic was nothing, but he saw if differently. The Ghost Town is a special place and people there relish the peacefulness and simplicity. My special deal for Terlingua residents paid off in a different way since they voted me best Bed & Breakfast in the region once or twice.

Sunday mornings were busiest. Some people, who had come to Alpine for an event on Saturday night, wanted an early breakfast before the long drive home. So I started breakfasts at 7 a.m. which meant getting ready from 6 a.m. On Sundays I also cooked breakfasts for the monthly rental tenants in the rooms in the garage. On one Sunday, I went across to the garage rooms to wake up one of the tenants, at her request. I heard a noise from one of the rooms I thought was empty since the tenant had gone home for the weekend. I noticed a dusty old Volvo parked outside. I pushed open the door, and saw two people in bed with a young child.

I had never seen them before, so I said "Who are you?" The young man said apologetically that they were driving back from Zacatecas, Mexico to Dallas. By the time they crossed into Texas and reached Alpine, they were exhausted, and it was 2 a.m. They saw the Bed & Breakfast sign, and tried the door to one of the rooms in the old garage building. The door was unlocked, and the bed made up. The rest of the house was asleep, including me. So they settled in. Their story was so convincing that I said "No problem, come into the house for breakfast. And you can pay me then".

After four years I was starting to feel part of the community, although I knew realistically that, among country people, that only happened after a generation or two. I always received great courtesy in my dealing with local people. Age might have had something to do with this; also the fact that I was a foreigner which I felt was better than a damn Yankee. The only time I got complaints was when people said I didn't wave to them as they passed in the street. The trouble was I was usually on my bicycle concentrating on the road and, in any event, not at a good angle to see them through the tinted glass of their vehicles.

After almost five years of operation I was feeling the strain of constant commitment. I found I was welcoming guests without the ready smile I showed previously. There was not much more to learn about the job, and The Corner House had proved itself, winning a Best Bed & Breakfast Award twice and helping to boost the local tourism economy. I put it on the market as a going concern complete with furniture and sold it quickly to a family from Houston who wanted to use it as their home. They are still there today, ten years later which makes me happy for them.

The other five communities in the area each has a different character, and appeals to a different sort of person. Marfa, 26 miles west of Alpine, was economically dead until art tourism happened. Already the aluminum boxes of minimalist artist Donald Judd, who arrived in Marfa in the 1970s, were an attraction for art-minded visitors who began to visit, but slowly. The town really started to expand with the arrival in 1997 from Hpatrons and investors Tim and Lynne Crowley, who opened a bookshop and a theater. Others followed: a restaurateur from New York, an hotelier from Austin and a gallery owner from Santa Fe. Suddenly Marfa was cool. Today, the community has a new life as an arts town, and a set of new residents. House prices have rocketed, and some Hispanics feel they have lost their town.

Fort Davis, to the north of Alpine, has changed much less and remains more traditional - their July 4

th

parade sets the standard. But it has also grown through its nearby residential communities. The area as a whole has seen an increase in population, and not just retirees attracted by the weather and the beauty of the landscape. Working age individuals and couples have arrived to start new businesses, and many have stayed. Now taking a yoga class or drinking a cup of espresso is considered normal behavior.

Marathon, the smallest community with a population of 600, has changed least externally. Yet here, too, there are more new residents who now live in the village year-round or who have second homes there. Eighty miles south of Alpine, Terlingua/Study Butte has grown larger and has lost some of its unconventionality but still retains an appeal for non-conformists and artists. To get an idea of the local characters, try sitting on the porch of the Terlingua Trading Company around sunset drinking a beer.

IN THE TRAVEL INDUSTRY

_______

2000's

TOURS TO MEXICO

TEXAS/MEXICO BORDER

The major tourist attraction in the sparsely populated tri county area of West Texas is Big Bend National Park. The three counties are Brewster, Jeff Davis and Presidio, with a combined area of 12,304 square miles and total population of 19,392 (2010); the area is also called the Davis Mountains/Big Bend region. The Big Bend National Park (BBNP) occupies 300,000 acres of desert, mountain and river and is visited by up to 400,000 persons a year. Its name, coined by an early surveyor, comes from the fact that the Rio Grande, flowing to the southeast and forming the southern boundary of the park, abruptly changes its course and turns almost 90 degrees forming a big bend for some miles before resuming it original direction. Across the river lies Mexico.

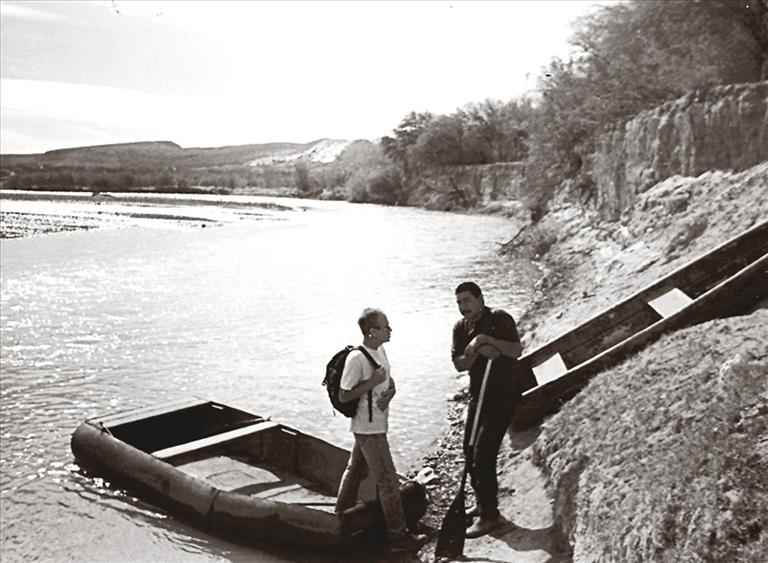

Before 9/11, BBNP visitors could cross the Rio Grande by boat to two small Mexican villages for a meal, a drink or to buy trinkets. A flat-bottom wooden boat, paddled by a Mexican, would cross over from the Mexican side and pick up anyone waiting. The novelty about these crossings was that there were no immigration or customs checks. For two dollars round trip, one could in three or four minutes pass from the order and richness of the US to the dust and poverty of a Mexican village.

The reason for this passport- and Customs-free waiver was the fact that a similar arrangement was in operation on the Canadian border and that there was a Mexican national park developing on the other side of the river. The U.S. National Park Service saw these unofficial border crossing points as an added attraction to the Big Bend National Park, and the chance to provide a quick peek at a different culture. The economic impact on Mexican communities across from the park, Boquillas and Santa Elena, was huge; the visiting tourists kept those villages alive. A third community, Paso Lajitas, across the Rio Grande from the resort of Lajitas offered a similar ferry service.

I first crossed The Rio Grande and visited all three communities in the mid-1990s when I moved to Alpine. In each case, after walking a short distance from the river I entered a small village with dirt streets, simple houses and a local shop. Sometimes there was a school, always a bar and a restaurant, and in the case of Boquillas, accommodation called The Buzzards Roost. Many of the villagers had family on the US side, but could not immigrate themselves. But before 9/11, they would regularly cross over to the US side for local shopping.

I visited several times, marveling at the contrast and enjoying Mexican culture at its simplest. On one visit I stayed at The Buzzards Roost Bed & Breakfast and the next day took a bus south to the town of Musquiz, five hours away. . I wrote a guidebook, "

Unofficial Border Crossings from Texas"

about these unique trips, and added a section to the back of the book on the Copper Canyon section to give the book wider appeal.

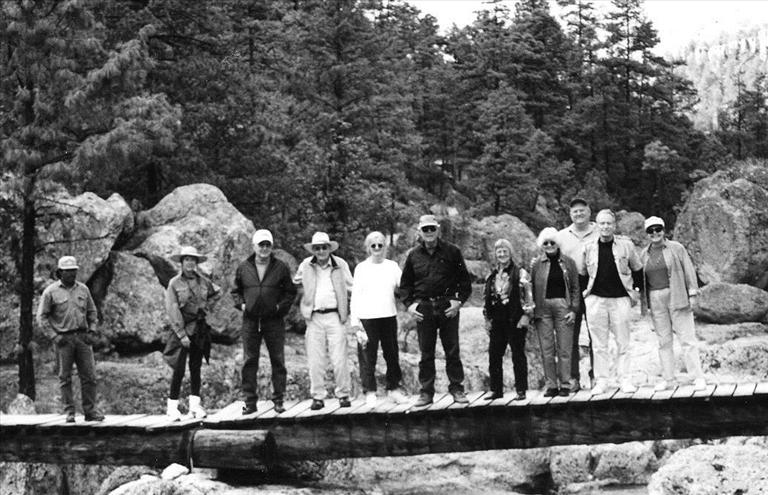

Beyond Boquillas is the Sierra Del Carmen range, a continuation of the Dead Horse Mountains on the US side. This range was significantly different from the Chisos Mountains in Big National Park. For one thing, it extended higher, to over 8,000 feet. More important, it had not been developed like the national park, so the terrain was wilder and the wildlife population, such as black bear, more numerous. Best of all, the private landowner wanted to encourage conservation-minded visitors from the US to come and explore. I took an exploratory trip to part of the range and decided to promote trips there from Alpine for local residents. The Mexican landowner, Alberto Garcia, flew into Alpine and gave a presentation at Sul Ross State University; this got the tours started.

An article in a Houston newspaper on my trips to this mountain wilderness brought me publicity, and for a couple of years I regularly took small groups on four-day trips to the Sierra del Carmen. To someone from the city the surprise of the boat crossing to a primitive Mexican village was added the excitement of loading into an old Suburban and driving up steep tracks to the top of the sierra where wood cabins, open fires and good Chihuahua steaks were ready. The suddenness of the change and the sense of adventuring into unknown nature added to the excitement. Sometimes Alberto Garza would act as host and guide, relishing sharing his private wonderland with visitors. There had been logging activity some time back on this range, but otherwise no development of this mountain landscape. Many energetic days were spent hiking these mountains and many a relaxing evening shared with Mexican friends around a campfire until a political event changed everything.

Following the attack of September 11, 2001, it was obvious that there would be changes to this unguarded sector of the international border. Five months later, the Department of Homeland Security announced that all three unofficial border crossings were closed, and the penalty for unauthorized crossing was $5,000.

Ten years later in 2011 the U.S. Government changed its policy and announced a new initiative to boost the concept of an international park spanning the Rio Grande. The crossing at Boquillas would be reopened, a new ferry boat supplied and visitors would be allowed to cross and, using a remote electronic processing, to return to the US at the same place on the same boat. What effect this will have in bringing life back to Boquillas remains to be seen, but certainly it surprised and delighted those on the U.S. side who felt the earlier decision was wrong.

COPPER CANYON, MEXICO

The Copper Canyon region, Mexico's answer to the Grand Canyon, is located in the southwest corner of the state of Chihuahua. Measuring roughly 110 by 80 miles it is part of the Sierra Madre Occidental range which runs north to south, a continuation of California's Sierra Nevada.

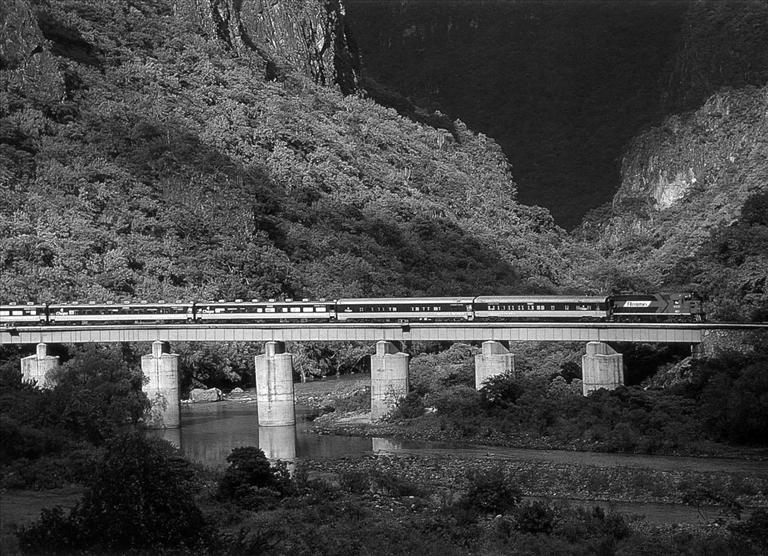

It comprises six major interlocking canyons, 4,000 to 6,000 feet deep, fed by rivers from smaller canyons. All this water drains to the west into the Rio Fuerte and ends up in the Sea of Cortez. It is best known for the Chihuahua al Pacifico railroad line, known as

El Chepe,

a major engineering feat which took 90 years to complete and opened in 1961. This single-track line runs 410 miles from Chihuahua City across the Continental Divide at 8,072 feet to Los Mochis, close to the Sea of Cortez.

From a tour operator's point of view, the region has everything: a memorable name, spectacular mountain and canyon scenery, easy access by daily train service, international airports at each end of the rail line, and a unique indigenous people, the Tarahumara.

EL CHEPE

TRAIN

TOUR GROUP

CROSSING THE RIO GRANDE

SIERRA DEL CARMEN

This semi nomadic tribe, around 70,000 strong, retreated to Sierra Madre Occidental when the Spanish invaded in the sixteenth century. Short, lean and handsome, the men wear loin clothes and huaraches (sandals). The women, who have precedence over men in their culture, wear long, colorful dresses. They are known for their running prowess and their proper name is

Raramuri,

which means "the fleet footed ones". They survive on subsistence farming of corn and beans; the women make handicrafts for the tourists and the men sometimes take jobs in the local economy.

In the late nineties I made my first exploratory trip to Copper Canyon. Carrying an excellent guidebook, The Handbook to Northern Mexico, I started the journey with a three-hour bus ride from the Mexican border town nearest to Alpine, Ojinaga, to the state capital, Chihuahua City. I had previous taken the rail journey from Chihuahua across the mountains to the coastal plain at El Fuerte. The destination of this trip was the bottom of one of the canyons, Batopilas Canyon, travelling by bus. Only two canyons, Batopilas and Urique, are served by bus and I knew from the guidebook I could catch a bus from Creel, the gateway to the Copper Canyon, early in the morning.

At Chihuahua's cavernous bus station on the outside of the city, I caught a second bus for the 180 mile drive to Creel. This was the last bus of the day, and it was running late. I arrived on a cold February evening in Creel to find all the accommodations were full since it was a religious festival. Without a bed I faced a freezing night at 7,000 feet, with not even a bus station to shelter in. Walking around Creel's plaza, I noticed light shining from a door with the sign "Margarita's Hostel" above. I knocked and got no reply, so I pushed the door open.

The door led directly into the kitchen where a wood stove gave off a good heat. I called out, looking for staff or guests. No one appeared so I lay down on a bench and slept the night away, warm and safe, and only slightly uncomfortable. A few people came in later, but no one seemed to take exception to a gringo sleeping on a bench in the kitchen. It was that sort of place.

It was still dark the next morning when I left Margaritas. I found the bus to Batopilas parked on the main street, Lopez Mateos. It was an old school bus which had previously seen duty in the USA. I climbed on board and found six other passengers, four local people and two backpackers. A young man turned up soon after and climbed into the driver's seat, and we were off. I knew we were going to drop down 5,000 feet into the canyon, and I just hoped it would be soon since the temperature was still freezing. We had 120 miles to cover, and the trip would take six hours.

After two hours of travel on a paved road, the bus turned off onto a dirt road track and I assumed our steep descent was about to start. Sure enough, but first we stopped briefly at a roadside shrine. It was light now and, looking down the steep mountain slope, we could see our road winding in tight turns down the mountain to reappear at the bottom of the canyon, some 5,000 feet below. The road was one track width only, with no guard rails. The driver, having given us a glimpse of the route ahead, turned on the engine and we moved off in low gear.

Almost at the bottom of the steep section, just as the gradient was leveling off towards the canyon bottom, the bus pulled to the side of the road and stopped. No one said anything and the driver offered no explanation. Five minutes went by, and I saw the driver was looking across the canyon to the far side. I followed his gaze, and caught sight of a figure loping down the mountain with long easy strides. Our next passenger I wondered?