For the Sake of All Living Things (26 page)

Read For the Sake of All Living Things Online

Authors: John M. Del Vecchio

“Bring them all,” a voice commanded.

Bu Ntoll, Nang thought. Bu Ntoll, the border sanctuary. He slid his hands under his ass and back to position.

The nine prisoners were led to the edge of the cliff. Nang kept his head down. He stumbled. Was lifted, prodded forward. Ceremoniously each was read a short, identical statement finding each guilty of war crimes and condemning each to death. Nang was seventh. He kept his head down. He breathed with his mouth open so he could hear and place the others, prisoners and guards.

“Tuay Teng,” the squad leader said.

“No!” The first man in line screamed. The sound of the lancer’s lunge. Then “Aaaa...” a fading scream. Silence.

“Hang Houk,” The lancer’s jab. No scream. A dull concussion as meat formed to rock with force.

“Vouch Voen.”

“Please.” A woman’s voice. “Please,” the woman begged.

Nang lifted his head. It was almost dark. He turned toward the woman. Below the cloth he could see the guards’ feet facing away, see the heavy vegetation and forest beyond. The lancer jabbed the woman in the spine. She shrieked.

Instead of knocking her forward, the soldier had impaled her with his spear. “Damn,” the lancer muttered. A dirty kill. As he stepped forward, about to put his boot in her back and yank out the lance, Nang spun. He snapped his arms outward. The wire unraveled. Vouch Voen shrieked madly as the soldier struggled with the lance. Nang sprang, a bound coil released, toward the forest. Guards caught turning back toward the entangled lancer and his victim first saw only a streak. Then one spun and opened fire. Nang dove half blind into trees, raced low on all fours deeper and deeper into the thickets. He ripped at the blindfold. The squad leader shouted. Shots cracked. The remaining prisoners were hurled off the cliff without hesitation. Screams. Silence. Moans filled the canyon. Nang slithered between, over, under vines and brush. Darkness settled. He raced on. There was no sound of pursuit.’

Bu Ntoll, he thought. I will send the next report from Bu Ntoll.

“Madam, what would you have us do with him?”

“Why did you insist on showing it to her?”

“She insists on knowing everything we do. Madam?”

Vathana stared at the remains between the barge captain and the crewman. “Perhaps,” the captain said in French, “I should have fed it to the crabs.”

Vathana shook her head. “No,” she whispered. “It is proper to have brought him here. You notified the authorities?”

“God!” The crewman cussed lowly, rolled his eyes to the sky.

“No, madam. We didn’t wish to be slowed.”

“He tried to board?”

“There were eight. Plus those firing from the bank. The others fled when Sarath fired and killed this one.”

Vathana bent to see better. The body was mangled. An arm was ripped off, both legs were broken and folded in horrifying positions. Flies swarmed above a ragged chest hole. Vathana straightened. “He’s so young.”

“They all looked young, madam. They all wore these checked kramas.”

“He’s not even as old as Samnang,” Vathana said absently. Involuntarily she grimaced, squeezed her eyes tightly shut. She shuddered, scrunched her shoulders toward her neck, pulled her shawl tight against the heavy afternoon rain.

“Madam...”

Vathana took a deep breath, exhaled slowly, opened her eyes. “What did Sarath fire at him to cause this?”

“An RPG. Kot hit him too. With the machine gun. What would you have—”

“Wrap him in this.” Vathana handed the captain her shawl. “Have Sarath and Kot take him to the pagoda.” Without the wrap Vathana’s abdomen bulged conspicuously.

“No good,” Sarath whispered to Kot. He had retreated to the sandbag wall about the pilothouse. “The baby will be born like it.”

“Maybe,” Kot whispered.

“We’ll go too,” Vathana said to the barge captain. “We must pray for his spirit. And ours.”

ON NEUTRALITY:

“...as defined by international law, specifically the Hague Convention of 1907, which states that, ‘A neutral country has the obligation not to allow its territory to be used by a belligerent. If the neutral country is unwilling or unable to prevent this, the other belligerent has the right to take appropriate counteraction.’ ”

—Harry G. Summers, Jr.,

Viet Nam War Almanac

I

T WAS SEVEN WEEKS

before Nang laid eyes on Bok Roh. For seven weeks the energy released from escaping death propelled him. He had never felt freer, never as a Khmer boy, never as a conscript, never as a yothea of Angkar Leou. As he approached his thirteenth birthday he was free to live, free to die, free to kill. He was strong and highly trained in all the survival arts—mental as well as physical.

Before he reached the border camp at Bu Ntoll, Nang trekked across the Southeast. At times he posed as a refugee, at times an orphan, at times a mute. He walked most of the distance. In Kampot he linked up with a Krahom guerrilla cell for several days without identifying himself or his mission. East of Takeo he discovered an NVA storage facility and shipping depot which made the warehouse areas of the Ho Chi Minh Trail look paltry. At Prey Lovea he was first assisted by an official of the Cambodian administration, then blocked by one from the parallel North Viet Namese regime, then assisted by a Viet Namese, then ordered into detention by Cambodians. All along the trail he simply asked Khmer families for rice or shelter. In the gracious tradition of Cambodians he was fed, often invited in. On these occasions he found his quick smile, infectious laugh and a simple story led him to be treated like a sibling. Each night Nang listened to stories of bravado and hardship under the parallel regimes; stories of atrocities along the border; stories of skirmishes between clashing foreign armies. Almost every week he found a way to send word to Mount Aural of what he’d heard.

At Neak Luong he worked for two days cleaning river barges. The crewmen entertained him during the evening with imagined tales of private battles with bandits. “The lady owner has armed us with machine guns,” one crewman told him. He produced an aged and worn AK-47. “She says, ‘Shoot and run.’ ” The man laughed. He rubbed his hand over the wooden stock. “ ‘Shoot and run.’ Ha! Do you think you can make this old scow run?” Aside he whispered, “The captain’s obtained rocket grenades, and launchers.”

“The lady owner, she says it’s okay?” Nang asked in broken Khmer.

“She’s too pregnant to think. Ha!”

“And the Prince’s army, they say okay?”

“Eh? Are you crazy? The less they know, the better.”

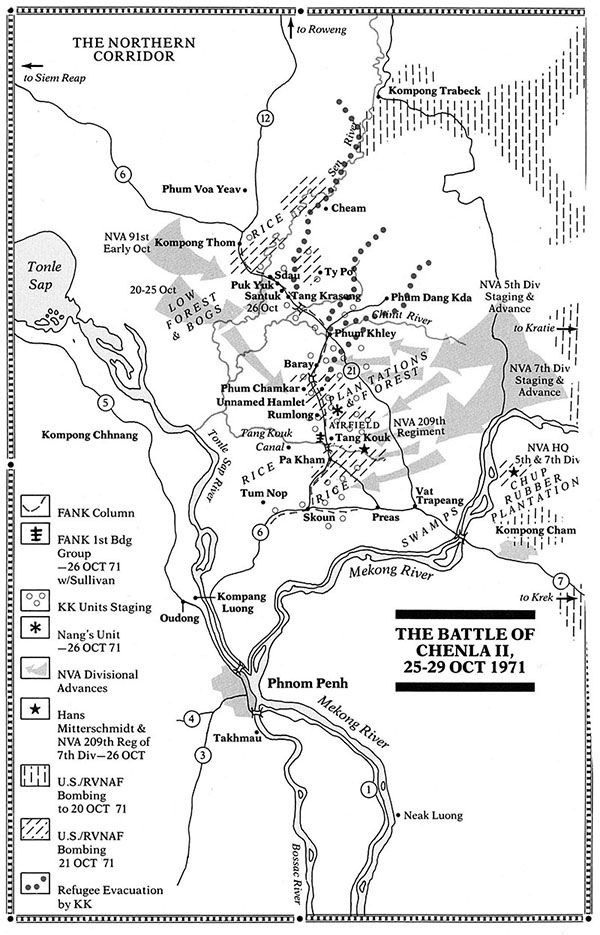

At Phum Chup, near the huge Chup Rubber Plantation Nang stole a Haklee truck and drove it for a mile toward the border before abandoning it in the quagmire of a paddy. From the back he stole an antitank mine which he quickly buried in the roadbed a dozen meters from the sinking truck. He waited, hidden across the road. In minutes a second Chinese truck and a sedan raced toward the stolen vehicles. The truck missed the detonator and stopped. Four soldiers jumped out, cussed, slogged into the paddy. Nang froze behind his concealment. The sedan parked behind the second truck. No one emerged. The windows were closed and dark. A soldier, dripping from the paddy, walked around the front of his truck. A rear window of the sedan opened and a man called out in Chinese. Nang was unable to understand the words. He imagined the man to be a bureaucrat with the Chinese Social Affairs Department, the ChiCom CIA, and he was delighted. The motor of the sedan churned, caught. The unseen driver edged back toward the road. The soldier stepped forward. Then, as if in one motion, the entire area lit, flashed yellow-orange-bright, a fireball roiling up, out. Then the concussion. It hit Nang, knocked him flat. Laughing, chunks of shrapnel crashing down about him, Nang fled across the paddy, down a dike path, running, laughing, free, easy, exhilarated.

For six nights he walked the road to Mimot and north toward Snuol. At Snuol Nang switched to forest trails. Where no inhabitants were supposed to live he stumbled into the midst of the putrid, loathsome camp. He stared in from the edge of the compound. Thousands of starving listless wraiths were rooted on the half-barren, gravel earthen hump. Most were old, toothless, wordless. They squatted or lay in shelters not suitable for pigs. A few infants lay in watery puddles of excrement. In spite of the torment there was no sound. Nang recognized the tribal dress of a few of the Mountaineers. An ancient Mnong man, the ivory plugs long fallen from his stretched limp earlobes, saw Nang, rose, fell and died. Three frail women cackled, dragged the body to the wooded edge, then returned, squatted, silent.

Nang circled the compound to where a score of Jarai elders lay in the shade of a flimsy blue plastic tarp. He emerged, hissed. No one turned. “Uncle,” he clucked. “Uncle, who are you?”

An old woman turned. The bones of her neck jutted like horns on a lizard’s back. She stared at the boy as if he were a mirage. “Great Aunt,” Nang said in Jarai. He came forward and squatted beside her. “You are Jarai?”

“All Jarai are dead,” the woman sighed.

“You are Jarai,” Nang stated.

“We used to live in the great mountains.” The woman’s voice was light, breathless. “Look how few are left. I am death.”

“Who killed you?” Nang asked.

“We’ve become accustomed to being dead.”

“Who?” Nang persisted.

“Does it matter?” The woman’s voice faded.

“Was it Bok Roh?” Nang insisted. The woman was too weary to answer. Those around her did not even look. Nang raged, “Bok Roh the giant?”

“We are the March of Tears,” a second woman whispered. “Here the march ends.”

“Was it Bok Roh?” Nang demanded.

“Yes,” the second woman answered. “Bok Roh sent us here. He killed the others. Bombs killed many.”

“Why don’t you go to Snuol?” Nang pressed.

“Anyone who leaves is shot,” the woman said. “Our land is empty. Our souls have been destroyed.”

Nang crept out, circled the squalid settlement, staying at the treeline. He circled again twenty meters farther out. Twice he saw trip wires. Bu Ntoll, he thought. A restrained smirk curled his lip.

It was cold though the wind had slackened. The sky grayed. Nang sat in a crotch of tree trunk and limb at the fringe of the North Viet Namese sanctuary. The military complex at Bu Ntoll was built on a 3000-foot peak set in a V-shaped inclusion of Cambodian territory wedging into South Viet Nam. Nang had slithered into the encampment, a small bivouac at the perimeter of the multisited sanctuary, on the third day of August 1969. For two days he sat, trancelike, without eating, without sleeping, vigilant yet inanimate, a machine, a camera and recorder, viewing, waiting, seeking, expecting without reason the appearance of Bok Roh. From his tree-crotch concealment he observed nitpicking cadre thoroughly inspect four distinct elements of clean, well-equipped troops, inspect their mission-specific equipment, saw hundreds of

dan cong

porters prepare to follow the soldiers with food and ammunition; watched as captured American jeeps carrying officers snaked up the covered one-lane road to the camp, through the camp, on toward the next site. For two days Nang watched as Russian and Chinese trucks arrived with more equipment and new, young troops. They are preparing for battle, he thought. He knew nothing of the plans.

On 5 August, one year to the day from his conscription, Nang spotted, amid a passing unit, Bok Roh. His inanimate trance turned colder. His eyes, penetrating the blocking vegetation, saw the scope of the camp, the scope of his revenge. It was time to move.

Nang slithered from the tree, crept past the guards, out of the camp. Then he rose. Do not concentrate on tools, he thought. He turned, walked back, up to the sentries, surrendered.

It was tricky. Nang wished to appear dumb but not so dumb as to be assigned to a porter unit. He wished to appear experienced but not so experienced as to be suspected of being capable of spying or double-agenting. He could not tell them he was a local boy or a guide or a FULRO soldier. If he told them he was Khmer Viet Minh they easily would be able to check: Bu Ntoll Mountain had two Khmer Viet Minh base sites. If he said he was Krahom they would hold him suspect, turn him over to the KVM. That wouldn’t do. That would separate him from his target and render him unable to accomplish his intelligence-garnering mission. Ideally, he thought, I can be assigned to a communal subcommissar. (Communal commissars were responsible for disseminating combat plans to local people just before or just as an ambush or attack was launched against an enemy element.) Nang felt secure, safe in age, in knowledge. I’ll let them know I can translate, he thought. Then I’ll hear plans.

“Take him to the field hospital,” the sergeant of the guard snapped. “Tie him.” To Nang, “What are you doing here? Your people have been told.”

Nang bowed, held his wrists so the guard could tie them. “Just follow me,” the guard indicated after the sergeant left. “He thinks,” he mumbled to another soldier, “this boy breeches security!?”

Nang told a doctor his name was Khat Doh. He told him he was from the Jarai village of Plei The more than a hundred kilometers north in the Ia Drang Valley and that he had been directed to Bu Ntoll by many people. The man accepted Nang’s story because he did not care if the little boy was telling the truth or lying. Nang told a second officer he had traveled for a few weeks with a FULRO platoon which had come south to Ban Me Thuot but that they had had no food, few arms and no organization. The officer sneered as if to say, “Of course. They’re ignorant

moi

.” Nang did not stop. He rattled on to his interrogator that he wished to kill the hairy meddling Americans who were behind the death of his father and the conquest of his village, that he wished to join the NVA in their attacks on the Americans. Nang clucked in Jarai, stammered in Khmer, butchered his few Viet Namese phrases. The officer noted it all.