For the Sake of All Living Things (34 page)

Read For the Sake of All Living Things Online

Authors: John M. Del Vecchio

WORLD VIEW

Half a world away, fissures in American public opinion, partly reconciled in the post-Tet 1968 period by the election of Richard Nixon again ruptured. On 3 November 1969 Nixon delivered to the American people his first major policy speech on Viet Nam. The President outlined a plan calling for gradual, though eventually total, withdrawal of American combat units and for an increased emphasis on Viet Namization (the Nixon doctrine, as applied to Viet Nam, of giving materiel and moral support, but no U.S. combat troops, to assist indigenous peoples in defending themselves from outside aggression). Though the immediate results showed that more than three quarters of all listeners favored the President’s policies, versus only six percent opposed, strong dormant forces in the U.S. Senate were jarred awake. J. William Fulbright promised Senate hearings to educate the “real silent majority” to the facts of the war, and Senate majority leader Mike Mansfield denounced the policy as the new administration’s adoption of Johnson’s war.

This was followed almost immediately (12 November) by the first sketchy stories of the massacre of Viet Namese civilians by American troops at Song My village, My Lai hamlet. On 20 November, the Cleveland

Plain Dealer

published photographs of the massacre. Then, on the 25th,

The New York Times

and other newspapers confirmed the atrocity to many skeptical Americans with headlines announcing the Army’s order that Lieutenant William Calley stand trial. By the beginning of 1970, My Lai had redivided the United States.

The effect of the Nixon doctrine announcement coupled with renewed American domestic turmoil was translated by Hanoi’s America watchers as ambiguous U.S. support. This encouraged the Communist factions to commit additional men and materiel to the battle for Cambodia.

The covert North Viet Namese thrust into the interior of Cambodia, spearheaded by the repatriation of the KVM, sent tidal waves through the Krahom movement, as it did through the Royal Government and much of Khmer society. In a nation at war, in a culture under attack, every military setback or victory affects every individual—to the very essence of his or her being.

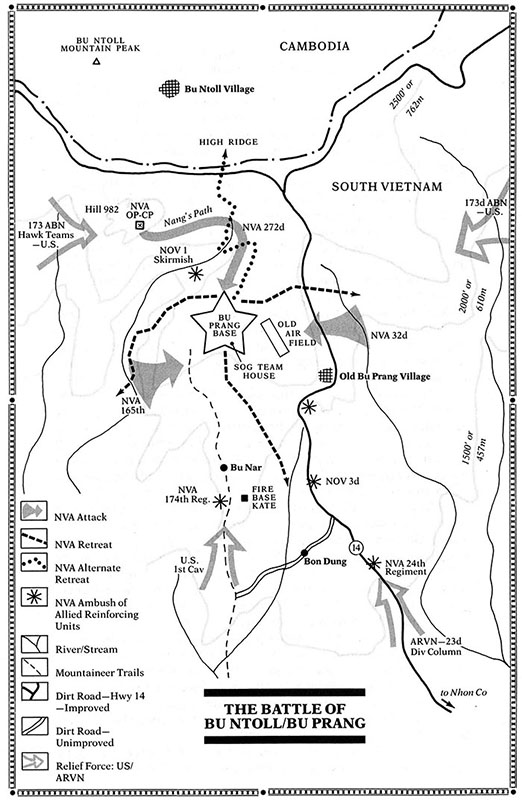

It is in this context that the battle of Chenla II must be understood, for each nuance of that battle touched the lives of every Cambodian. Chenla II was a tsunami which reverberated throughout the Khmer Basin, bouncing, as waves bounce, off the surrounding mountains, sending secondary waves crashing into and washing over each other in the central area known as the Northern Corridor (see map), a tempest slowly, violently splintering an entire nation, a storm which would have two eyes, the first resulting from gusting multiple engagements leading to the worst battlefield defeat of the war.

THE REPUBLIC OF CAMBODIA RISING

Hanoi could easily devour both Cambodia and what is left of Laos if it were not faced with US opposition. There are enough North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops in Cambodia today to seize [the] country.

—

C. L. Sulzberger, paraphrasing Norodom Sihanouk, in

The Indianapolis News

,

18 March 1970

“A

RE YOU HUNGRY?” NANG

spoke slowly to the children though his inner pace was frantic. After only one week at Mount Aural he had been sent to Stung Treng to help accelerate Krahom recruitment. “Don’t be afraid,” he said. “We guarantee everyone will share equally in the nation’s food.” It was not the assignment he’d wanted. Every day he asked why. Why had Met Sar sent him away so quickly, away to these children, away when so much was happening elsewhere? “Here,” Nang said, “peasants work twelve hours a day. In Phnom Penh, government functionaries work two! They eat well. They pay no taxes.”

“You see.” Met Phan smiled. “Comrade Rang has been to the front. He knows victory is inevitable. He has killed enemy soldiers. He has blown up enemy tanks. He’s not much older than you.”

Nang bowed to the boys and girls. They sat elbow to elbow in the hot shack, sat in the posture of perfect attention as they had learned, sat in awe of Met Nang, to them Comrade Rang, a mysterious figure sent to them in their mysterious back-street hovel, sat in awe in the shadows as the January dry season sun baked the sleepy alley.

“Comrade Rang has been sent to us to teach us courage,” Phan said. He sat with the children, sat in perfect egalitarian posture, eyes on Nang.

“The Americans,” Nang whispered, “killed my uncle. He had been wounded in the leg and taken prisoner. While he still lived, they stabbed him in the mouth and cut out his tongue.” Nang paused. He trembled at the recollection, at the sight which he forced himself to believe. “The imperialists have poisoned the mind of Prince Sihanouk. Royal soldiers killed my whole family. If we show fear they will kill us all, but if we have courage...”

The youngest child, a girl of seven, watched Nang with widening eyes. He spoke with such feeling and gentleness she wanted to touch his hand, yet his words carried such horror she fought to control the undefined terror gripping her. Behind her an untrained boy of eleven stiffened. His imagination placed him in this soldier’s tale; his resolve to be courageous stiffened.

Each child had slipped away from a parent, each having been recruited because each had had a father or mother killed in the low-level guerrilla war of the preceding years. They were the core of Phan’s Stung Treng Children’s Brigade. Phan, a covert political officer of both the Krahom and the Khmer Viet Minh, had started the clandestine unit in 1967 with one boy whose father had been shot by government soldiers during an anti-government demonstration. Phan had asked the boy if he would like assistance in gaining reparation and the boy had followed him. “Tell me three of your friends,” Phan had said at their second meeting. “Bring a friend,” he urged during the third. Each child, once lured, hooked, sworn to secrecy, was required to recruit two friends. “One becomes three,” Phan repeated the Communist axiom. “Three become nine.” From early 1967 to mid-1969 recruitment had been difficult but tactics and the situation were changing. By 1970 Phan had nineteen cells of children, three to six youngsters per cell. Nang had come to bolster that recruitment.

“Children can be very courageous.” Nang’s eyes were soft. These children, he knew, would never be sent to advanced Communist training schools. They were not destined to become cadre; there would be no School of the Cruel, no ideological indoctrination. For them there would be only the underground school, the fetid back-alley shack, the brief afternoon classes in hate, the first all-night patrol, the first act of terrorism, and then death—death in the meat grinder of war, death to the naive, pushed knowingly into the funnel by ideologically secure cadres who not only would feed that grinder, but had justified in their minds their duty to feed it the most expendable, until the grinder itself ran down and the cadres could control it unilaterally. Nang continued. “Children can turn the tide of battle,” he said. “They can win wars. You know imperialists are trying to take the country from the people, eh? If you are a coward you will live your life in shame in a country owned by others. It’s better to die with courage than to live with shame.”

Nang paused. He lowered his head, closed his eyes. In the steaming motionless silence the little girl in the front and the boy in back leaned imperceptibly forward. Even Phan strained his ears to hear Nang’s next utterance though Phan had sat through the show four times with four cells and would listen fourteen more times with perfect attention. “Once,” Nang whispered, his eyes shut in pain, “we were caught in the crossfire of two American tanks. Met Peou snuck from his hiding place. He was so small. Only six years old. He didn’t wear any pants. He ran forward crying as the tanks came toward us. Under his shirt he had dynamite. When he reached the first tank it stopped. The enemy stopped firing and one soldier came out. Met Peou pulled the cord under his shirt and killed the long-nose. Peou stopped the tanks long enough for us to capture them and kill the crews. He was my little brother. His life is better than mine. He had more courage and he has no shame.”

Two girls wept. Nang let tears come to his eyes. He was pleased by the children’s reaction. It deepened his belief in the cause, the just cause of the Khmer Krahom, his cause. And...the tears were not entirely fake. In his mind he saw his own little brother and he saw him explode. Nineteen times in Stung Treng, a hundred times in the Northeast, he saw that image and it grew to be true and he hated it and a hundred times he chased away the intrusive thought and asked himself why—why had Sar sent him back so close to home?

Then came the government announcement; then Nang’s recall.

Vathana opened her eyes. Teck’s head was curled down upon his chest. From behind him she could see only the skinny shoulder of a headless form protruding above the coverlet. Between them lay the two-month-old infant, Samnang, asleep, angelic, snoring a high thin infant snore. Vathana cupped the baby to her side. She looked up. The canopy of sheer white mosquito netting fell in graceful folds about them like a protective cocoon. Teck snorted, rolled to his back, arched, melted back into the mattress like a deflating balloon. “Sophan,” Vathana called softly.

In the first weeks after Vathana’s trauma and the birth of his son, Teck had been more attentive than at any time since their wedding. Grudgingly he’d stumbled through the intricacies of river-barge management, on one occasion actually talking to the captain on the wharf. During those weeks he neither went dancing nor smoked heroin, and to him Cambodia seemed to open itself, denude itself, stand before him in raunch corrupt ugliness without the filter of his mother or the firm control of his father. He cowered. He wanted to hide, to run. But he held together and for that his mother rewarded him. One evening, she brought him to Phnom Penh to a most fashionable party; a party where wines flowed and young women chatted softly in French with handsome military men; a party where the undercurrent of conversation amongst the uniformed officers was of the Prince, the war, the rumor of the fabled white crocodile foreshadowing change, though on the surface no deep concern was expressed.

The dazzle of the party, of his mother’s growing association with the haut monde, captivated Teck. Capriciously he resolved to have his father purchase for him a commission into the Royal forces. Then he returned to Neak Luong, saw his weary wife up, about, able if still frail, and his resolve dissipated. Slowly he slipped into former habits.

The infant wheezed. Vathana hugged him, kissed him, then slipped her arm from around him to tug the mosquito net from its tuck beneath the mattress. “Sophan,” she called again. She rose.

A stout woman came and bowed. “Yes’m.” Sophan bowed again. She was one of the hundreds of women Vathana had rescued, had taken into her expanding refugee center after their homes near the border had been destroyed. Vathana had not particularly noticed Sophan amid the border people, but Sophan had chosen her, had attached herself to Vathana because she no longer had a family. Whenever Teck had left Vathana unattended in the hospital, it had been Sophan who had cared for her.

“Take the baby and nurse him. Then swaddle him in the sunflower blanket with the emerald-green bunting. His grandfather’s coming.”

Pech Lim Song burst upon the apartment like sun rays breaking through sluggish clouds. Teck was still in bed. Half the morning had passed. “Let me hold my grandson,” Mister Pech said. His speech was light, his movements quick, gentle, his face radiant as he cooed to the infant and praised his daughter-in-law. Then Teck emerged. The clouds thickened.

“Crocodiles consume the countryside...” Mister Pech said sarcastically. He stood before Vathana’s work desk eyeing the elegantly framed photo of Prince Sihanouk. “...while the nation’s young men sleep.”

“How is your health, Father?” Teck bowed though Mister Pech remained with his back to his son.

“They’re closing in,” Mister Pech said. “I quote the Prince. North Viet Namese armed penetration into Cambodia coupled with ‘an energetic subversion campaign aimed at

my

peasants, workers, Buddhist monks...attempting to organize a “Khmer popular uprising” against the monarchy whom they accuse of selling out to French colonialism.’ Yes! French! Those were his words! Nineteen fifty-three! ‘Anti-Sihanouk propaganda...terrorism...assassination of Khmer loyalists, officials and civil servants...’ Their objectives haven’t changed but their ability has blossomed a hundredfold.”