Forever Barbie (2 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

Lily understood that beauty is only the raw material of conquest and that to

convert it to success, other arts are required. She knew that to betray any

sense of superiority was a subtler form of the stupidity her mother

denounced, and it did not take her long to learn that a beauty needs more

tact than the possessor of an average set of features.

—EDITH WHARTON,

The House of Mirth

The daughter is for the mother at once her double and another person

. . .

she saddles her child with her own destiny: a way of proudly laying claim

to her own femininity and also a way of revenging herself for it. The same

process is to be found in pederasts, drug addicts, in all who at once take

pride in belonging to a certain confraternity and feel humiliated by the

association.

—SlMONE DE BEAUVOIR,

The Second Sex

No nude, however abstract, should fail to arouse in the spectator some vestige

of erotic feeling.

—KENNETH CLARK,

The Nude

T

he theme of the convention was "Wedding Dreams," and appropriately it was held in Niagara Falls, the honeymoon capital, a

setting of fierce natural beauty pimpled with fast-food joints and tawdry motels. The delegates were not newlyweds who had

come to cuddle aboard the

Maid of the Mist,

poignantly hopeful that their union, unlike half of all American marriages, would last. They were not children, who had come

to goggle at the cataract over which dozens of cartoon characters had plunged in barrels and miraculously survived. Nor were

they shoppers attracted by Niagara's other big draw—the Factory Outlet Mall—where such brand names as Danskin and Benetton,

Reebok and Burberrys, Mikasa and Revere Ware could be purchased for as much as 70 percent off retail.

They were, however, consumers, many of whom had been taught a style of consumption by the very object they were convening

to celebrate. They had fled the turquoise sky and the outdoor pagentry for the dim, cramped ballroom of the Radisson Hotel.

There were hundreds of them: southern ladies in creaseless pant suits dragging befuddled Rotary Club-member husbands; women

in T-shirts from Saskatoon and Pittsburgh; stylish young men from Manhattan and West Hollywood. There were housewives and

professional women; single people, married people, severely corpulent people, and bony, gangling people. A thirtysomething

female from Tyler, Texas, volunteered that she had the same measurements as Twiggy, except that she was one inch wider in

the hips. There were people from Austria and Guadeloupe and Scotland. Considering the purpose of the gathering, there were

surprisingly few blond people.

These were delegates to the 1992 Barbie-doll collectors' convention, a celebration of the ultimate American girl-thing, an

entity too perfect to be made of flesh but rather forged out of mole-free, blemish-resistant, non-biodegradable plastic. Narrow

of waist, slender of hip, and generous of bosom, she was the ideal of postwar feminine beauty when Mattel, Inc., introduced

her in 1959—one year before the founding of Overeaters Anonymous, two years before Weight Watchers, and many years before

Carol Doda pioneered a new use for silicone. (Unless I am discussing the doll as a sculpture, I will use "she" to refer to

Barbie; Barbie is made up of two distinct components: the doll-as-physical-object and the doll-as-invented-personality.) At

other collector events, I have witnessed ambivalence toward the doll—T-shirts, for instance, emblazoned with: "I wanna be

like Barbie. The bitch has everything." But this crowd took its polyvinyl heroine seriously.

Of course, people tend to take things seriously when money is involved, and Barbie-collecting, particularly for dealers, has

become a big business. The earliest version of the doll, a so-called Number One, distinguished by a tiny hole in each foot,

has fetched as much as $4,000. The "Side-part American Girl," which features a variation on a pageboy haircut, has brought

in $3,000. And because children tend to have a destructive effect on tiny accessories, the compact from Barbie's "Roman Holiday"

ensemble, an object no bigger than a baby's thumbnail, has gone for $800. While Barbie-collecting has not replaced baseball

as the national pastime, it has, in the fourteen years since the first Barbie convention in Queens, New York, moved from the

margins to the mainstream. Over twenty thousand readers buy

Barbie Bazaar,

a glossy bimonthly magazine with full-color, seductively styled photos of old Barbie paraphernalia. And twenty thousand is

not an insignificant number of disciples. Christianity, after all, started out with only eleven.

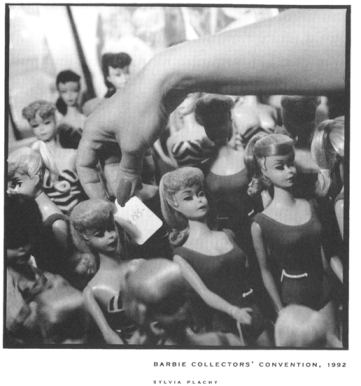

In the shadowy salesroom, amid vinyl cases and cardboard dreamhouses, thousands of Barbies and Barbie's friends were strewn

atop one another— naked—suggesting some disturbing hybrid of Woodstock and a Calvin Klein Obsession ad. Others stood bravely—clothed—held

up by wire stands. Some were in their original cartons; "NRFB" is collector code for "never removed from box." Still others

were limbless, headless, or missing a hand. "Good for parts," a dealer explained. Buyers, wary of deceitful dealers, ran weathered

fingers over each small, hard torso, probing for scratches, tooth marks, or, worst of all, for an undeclared spruce-up. Even

a skillful application of fresh paint can devalue a doll, as does hair that has been rerooted.

Emotions ran high as deals were cut. A stocky woman in jeans haggled furiously over Barbie's 1963 roadster; I later saw her

in the lobby, cradling the car as if it were her firstborn child. Others schmoozed with reliable, well-known dealers—Los Angeles-based

Joe Blitman, author of

Vive La

Francie,

an homage to Francie, Barbie's small-breasted cousin who was born in 1966 and lasted until 1975; and Sarah Sink Eames, from

Boones Mill, Virginia, author of

Barbie Fashion,

a photographic record of the doll's wardrobe. I learned the value of established dealers when I bought "Queen of the Prom,"

the 1961 Barbie board game, from a shifty-eyed woman who was not a convention regular. "The set's kind of beat-up," she told

me, "but all the pieces are authentic." Right, lady. Barbie's allowance, I discovered when I played the game, was five dollars.

The smallest denomination in the set she sold me was $100. (The bills were from another game.)

Selling was not the only action at the convention. There was a fashion show in which collectors arranged their not-especially-Barbie-esque

bodies into life-size versions of their favorite Barbie outfits. There was a competition of dioramas illustrating the theme

"Wedding Dreams"; one, which did not strike me as lighthearted, featured a male doll (not Ken) recoiling in fear and horror

from Barbie and, implicitly, Woman, on his wedding night. (His face had been whitened and his eyes widened into circles.)

Employees of Mattel were treated like rock stars. Early on the second night of the convention, veteran costume designer Carol

Spencer, who has been dressing Barbie since 1963, settled down in the hotel lobby to autograph boxes of "Benefit Ball Barbie,"

one of her creations in Mattel's Classique Collection, a series promoting its in-house designers. At eleven, she was still

signing.

Intense feelings about Barbie do not run exclusively toward love. For every mother who embraces Barbie as a traditional toy

and eagerly introduces her daughter to the doll, there is another mother who tries to banish Barbie from the house. For every

fluffy blond cheerleader who leaps breast-forward into an exaggerated gender role, there is a recovering bulimic who refuses

to wear dresses and blames Barbie for her ordeal. For every collector to whom the amassing of Barbie objects is a language

more exquisite than words, there is a fiction writer or poet or visual artist for whom Barbie is muse and metaphor—and whose

message concerns class inequities or the dark evanescence of childhood sexuality.

Barbie may be the most potent icon of American popular culture in the late twentieth century. She was a subject of the late

pop artist Andy Warhol, and when I read Arthur C. Danto's review of Warhol's 1989 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art,

I thought of her. Danto wrote that pop art's goal was elevating the commonplace; but what, he wondered, would happen when

the commonplace ceased to be commonplace? How would future generations interpret Warhol's paintings—generations for which

Brillo boxes, Campbell soup labels, and famous faces from the 1960s and '70s would not be instantly identifiable?

Danto's meditations got me thinking about the impermanence of living icons. What, for instance, is Valentino to us today?

A shadow jerking across a black-and-white screen, campy at best, no more an image of smoldering sex appeal than, say, Lassie.

What is Dietrich? To the millions who read her daughter's vindictive, best-selling biography, she is an amphetamine-ridden

drunk with disgusting gynecological problems, so leery of hospitals that she let a wound in her thigh fester until her leg

was threatened with amputation. What is Marilyn? A caricature, a corpse, the subject of tedious documentaries linking her

to RFK and JFK. And what is Elvis? To anyone over forty, he's probably still the sexy crooner from Tupelo; but younger people

recall him as a bloated junkie encrusted with more rhinestones than Liberace.

Barbie has an advantage over all of them. She can never bloat. She has no children to betray her. Nor can she rot, wrinkle,

overdose, or go out of style. Mattel has hundreds of people—designers, marketers, market researchers—whose full-time job it

is continually to reinvent her. In 1993, fresh versions of the doll did a billion dollars' worth of business. Based on its

unit sales, Mattel calculates that every second, somewhere in the world, two Barbies are sold.

Given the emergence of the doll as a symbol in literature and art—not to mention as a merchandising phenomenon—it's time to

take a closer look at how Barbie developed and what her ascendancy might signify, even though it's impossible to calculate

the doll's influence in any sort of clinical study. By the time children play with Barbie, they have too many other factors

in their environment to be able to link a specific behavior trait with a particular toy. But because Barbie has both shaped

and responded to the marketplace, it's possible to study her as a reflection of American popular cultural values and notions

about femininity. Her houses and friends and clothes provide a window onto the often contradictory demands that the culture

has placed upon women.

Barbie was knocked off from the

"Bild

Lilli" doll, a lascivious plaything for adult men that was based on a postwar comic character in the

Bild

Zeitung,

a downscale German newspaper similar to America's

National

Enquirer.

The doll, sold principally in tobacco shops, was marketed as a sort of three-dimensional pinup. In her cartoon incarnation,

Lilli was not merely a doxie, she was a

German

doxie—an ice-blond, pixie-nosed specimen of an Aryan ideal—who may have known hardship during the war, but as long as there

were men with checkbooks, was not going to suffer again.

Significantly, the Barbie doll was invented by a woman, Mattel cofounder Ruth Handler, who later established and ran "Nearly

Me," a firm that designed and marketed mastectomy prostheses. (As she herself has put it, "My life has been spent going from

breasts to breasts.") After Ruth and her husband Elliot, with whom she founded Mattel, left the company in 1975, women have

continued to be the key decision makers on the Barbie line; the company's current COO, a fortyish ex-cosmetics marketer given

to wearing Chanel suits, has been so involved with the doll that the

Los Angeles Times

dubbed her "Barbie's Doting Sister." In many ways, this makes Barbie a toy designed by women for women to teach women what—for

better or worse— is expected of them by society.

Through the efforts of an overzealous publicist, Mattel engineer Jack Ryan, a former husband of Zsa Zsa Gabor, received credit

for Barbie in his obituary. Actually, he merely held patents on the waist and knee joints in a later version of the doll;

he had little to do with the original. If anyone should share recognition for inventing Barbie it is Charlotte Johnson, Barbie's

first dress designer, whom Handler plucked from a teaching job and installed in Tokyo for a year to supervise the production

of the doll's original twenty-two outfits.

Handler tries to downplay Barbie's resemblance to Lilli, but I think she should flaunt it. Physically the two are virtually

identical; in terms of ethos, they couldn't be more dissimilar. In creating Barbie, Handler credits herself with having fleshed

out a two-dimensional paper doll. This does not, however, do justice to her genius. She took Lilli, whom Ryan described as

a "hooker or an actress between performances," and recast her as the whole-some all-American girl. Handler knew her market;

if any one character trait distinguishes the American middle class, both today and in 1959, it is an obsession with respectability.

This is not to say the middle class is indifferent to sex, but that it defines itself in contrast to the classes below it

by its display of public propriety. Pornography targeted to the middle class, for example, must have a vaneer of artistic

or literary pretense--hence

Playboy

, the picture book men can also buy "for the articles."

Barbie and Lilli symbolize the link between the Old World and the New. America is a nation colonized by riffraff; the

Mayflower

was filled with petty criminals and the down-and-out. When Moll Flanders, to cite an emblematic floozy, took off for our

shores, she was running from the law. Consequently, what could be more American than being an unimpeachable citizen with a

sordid, embarrassing forebear in Europe?

TO FIRST-GENERATION BARBIE OWNERS, OF WHICH I WAS one, Barbie was a revelation. She didn't teach us to nurture, like our clinging,

dependent Betsy Wetsys and Chatty Cathys. She taught us independence. Barbie was her own woman. She could invent herself with

a costume change: sing a solo in the spotlight one minute, pilot a starship the next. She was Grace Slick and Sally Ride,

Marie Osmond and Marie Curie. She was all that we could be and—if you calculate what at human scale would translate to a thirty-nine-inch

bust—more than we could be. And certainly more than we were . . . at six and seven and eight when she appeared and sank her

jungle-red talons into our inner lives.