Forever Barbie (3 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

Or into my inner life, anyway. After I begged my mother for a Barbie, she reluctantly gave me a Midge—Barbie's ugly sidekick,

who was named for an insect and had blemishes painted on her face. When I complained, she compounded the error by simultaneously

giving me a Barbie and a Ken. I still remember Midge's anguish—her sense of isolation—at having to tag along after a couple.

In my subsequent doll play, Ken rejected Barbie and forged a tight platonic bond with Midge. He did not, however, reject Barbie's

clothes—and the more girlish the better.

To study Barbie, one sometimes has to hold seemingly contradictory ideas in one's head at the same time—which, as F. Scott

Fitzgerald has said, is "the test of a first-rate intelligence." The doll functions like a Rorschach test; people project

wildly dissimilar and often opposing fantasies on it. Barbie may be a universally recognized image, but what she represents

in a child's inner life can be as personal as a fingerprint. It was once fashionable to tar Barbie as a materialistic dumbbell,

and for some older feminists it still is; columnists Anna Quindlen and Ellen Goodman seem to be competing to chalk up the

greatest number of attacks. Those of us young enough to have played with Barbie, however, realize the case is far from open

and shut. In part, this is because imaginative little girls rarely play with products the way manufacturers expect them to.

But it also has to do with the products themselves: at worst, Barbie projected an anomalous message; at best, she was a sort

of feminist pioneer. And her meaning, like her face, has not been static over time.

Before the divorce epidemic that swept America in the late sixties, Barbie's universe and that of the suburban nuclear family

were light years apart. There were no parents or husbands or offspring in Barbie's world; she didn't define herself through

relationships of responsibility to men or to her family. Nor was Barbie a numb, frustrated

Hausfrau

out of

The Feminine

Mystique.

In the doll's early years, Handler turned down a vacuum company's offer to make a Barbie-sized vacuum because Barbie didn't

do what Charlotte Johnson termed "rough housework." When Thorstein Veblen formulated his

Theory of the Leisure Class,

women were expected to perform vicarious leisure and vicarious consumption to show that their husbands were prosperous. But

Barbie had no husband. Based on the career outfits in her first wardrobe, she earned her keep modeling and designing clothes.

Her leisure and consumption were a testimony to herself.

True, she had a boyfriend, but he was a lackluster fellow, a mere accessory. Mattel, in fact, never wanted to produce Ken;

male figure dolls had traditionally been losers in the marketplace. But consumers so pushed for a boyfriend doll that Mattel

finally released Ken in 1961. The reason for their demand was obvious. Barbie taught girls what was expected of women, and

a woman in the fifties would have been a failure without a male consort, even a drip with seriously abridged genitalia who

wasn't very important in her life.

Feminism notwithstanding, the same appears true today, though many of my young friends who own Barbies have embraced a weirdly

polygamous approach to marriage, in which an average of eight female dolls share a single overextended Ken. Some mothers facetiously

speculate that they are acting out the so-called "man shortage," still referred to by dinner-party hostesses despite its having

been discredited by Susan Faludi in

Backlash.

My theory, however, is that smart little girls were made uneasy by the late-eighties version of Ken. Unlike the bright-eyed,

innocent Ken with whom I grew up, the later model bears a troubling resemblance to William Kennedy Smith: His brow is low,

his neck thick, and his eyes too close together.

With its 1993 "Earring Magic Ken," Mattel perhaps overdid his retreat from heterosexual virility. True, the doll has a smarter-looking

face, but between his earring, lavender vest, and what newspapers euphemized as a "ring pendant" ("cock ring" wouldn't, presumably,

play to a family audience), he would have fit right in on Christopher Street. Watching my jaw drop at the sight of the doll

at Toy Fair, Mattel publicist Donna Gibbs assured me that an earring in one's left ear was innocuous. "Of course," I said

feebly, "the same ear in which Joey Buttafuoco wears his."

Barbie, too, has changed her look more than once through the years, though her body has remained essentially unaltered. From

an art history standpoint—and Barbie, significantly, has been copyrighted as a work of art—her most radical change came in

1971, and was a direct reflection of the sexual revolution. Until then, Barbie's eyes had been cast down and to one side—the

averted, submissive gaze that characterized female nudes, particularly those of a pornographic nature, from the Renaissance

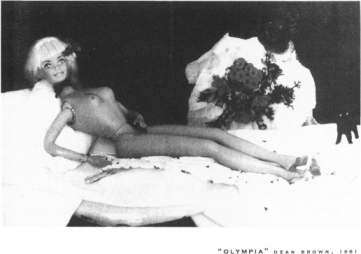

until the nineteenth century. What had been so shocking about Manet's

Olympia

(1865) was that the model was both naked and unabashedly staring at the viewer. By 1971, however, when America had begun to

accept the idea that a woman could be both sexual and unashamed, Barbie, in her "Malibu" incarnation, was allowed to have

that body and look straight ahead.

The Barbie doll had its first overhaul and face change in 1967, when it acquired eyelashes and a rotating waist. Although

the new "Twist 'N Turn" Barbie was not that different from the rigid old one—its gaze was still sidelong— the way it was promoted

was not. Girls who traded in their old, beloved Barbies were given a discount on the new model. Twist 'N Turn introduced car

designer Harley Earl's idea of "dynamic obsolescence" to doll bodies. Where once only doll fashions had changed, now the doll

itself changed; each year until the eighties, the doll's body would be engineered to perform some new trick—clutch a telephone,

hit a tennis ball, even tilt its head back and smooch. Taste was not a big factor in devising the new dolls; in 1975, Mattel

came out with "Growing Up Skipper," a preteen doll that, when you shoved its arm backward, sprouted breasts.

Fans of conspiracy theories will be disappointed to learn that Barbie's proportions were not the result of some misogynistic

plot. They were dictated by the mechanics of clothing construction. The doll is one-sixth the size of a person, but the fabrics

she wears are scaled for people. Barbie's middle, her first designer explained, had to be disproportionately narrow to look

proportional in clothes. The inner seam on the waistband of a skirt involves four layers of cloth—and four thicknesses of

human-scale fabric on a one-sixth-human-scale doll would cause the doll's waist to appear dramatically larger than her hips.

It is one thing for a sexually initiated adult to snicker over the doll's anatomically inaccurate body, quite another to recall

how she looked to us when we were children: terrifying yet beguiling; as charged and puzzling as sexuality itself. In the

late fifties and early sixties, there was no talk of condoms in the schools,

National Geographic

was a kid's idea of a racy magazine, and the nearest thing to a sexually explicit music video was Annette Funicello bouncing

around with the Mouseketeers. Barbie, with her shocking torpedo orbs, and Ken with his mysterious genital bulge, were the

extent of our exposure to the secrets of adulthood. Sex is less shrouded now than it was thirty years ago, but today's young

Barbie owners are still using the doll to unravel the mystery of gender differences.

Of course, these days, kids have a great deal more to puzzle out. One used to wake up in the morning confident of certain

things—among them that there were two genders, masculine and feminine, and that "masculine" was attached to males, "feminine"

to females. But on the frontiers of medicine and philosophy, this certainty has been questioned. Geneticists recognize the

existence of at least five genders; prenatal hormonal irregularities can, for instance, cause fetuses that are chromosomally

female to develop as anatomical males and fetuses that are chromosomally male to develop as anatomical females. Then there

are feminist theorists such as Judith Butler who argue that there is no gender at all.

"Gender is

a kind of imitation for which there is no original,"

Butler has written. It is something performed, artificial, a "phantasmic ideal of heterosexual identity." All gendering,

consequently, is drag, "a kind of impersonation and approximation."

No one disputes that from a young age boys and girls behave differently, but the jury is still out on why. Is such behavior

rooted in biology or social conditioning? I think it's possible to look at femininity as a performance— or "womanliness as

a masquerade," to borrow from Joan Riviere, a female Freudian who labeled the phenomenon in 1929—without chucking the possibility

of biological differences.

Indeed, some of Barbie's most ardent imitators are probably not what Carole King had in mind when she wrote "Natural Woman."

Many drag queens proudly cite Barbie's influence; as a child, singer Ru-Paul not only collected Barbies but cut off their

breasts. Barbie has, in fact, a drag queen's body: broad shoulders and narrow hips, which are quintessentially male, and exaggerated

breasts, which aren't. Then there are biological women whose emulation of Barbie has relied heavily on artifice: the Barbi

Twins, identical

Playboy

covergirls who maintain their wasp waists through a diet of Beech-Nut strained veal; and Cindy Jackson, the London-based cosmetic

surgery maven who has had more than twenty operations to make her resemble the doll.

When Ella King Torrey, a friend of mine and consultant on this book, began researching Barbie at Yale University in 1979,

her work was considered cutting-edge and controversial. But these days everybody's deconstructing the doll. Barbie has been

the subject of papers presented at the Modern Language Association's 1992 convention and the Ninth Berkshire Conference on

the History of Women; rarely does a pop culture conference pass without some mention of the postmodern female fetish figure.

Gilles Brougere, a French sociologist, has conducted an exhaustive study of French women and children to determine how different

age groups perceive the doll. When scholars deal with Barbie, however, they often take a single aspect of the doll and construct

an argument around it. I have resisted that approach. What fascinates me is the whole, ragged, contradictory story—its intrigues,

its inconsistencies, and the personalities of its players.

I've tried to pin down exactly what happened in Barbie's first years. Mattel's focus on the future, which may be the secret

of its success, has been at the expense of its past. The company has no archive. This may help conceal its embarrassments,

but it has also buried its achievements—such as subsidizing Shindana Toys in response to the 1965 Watts riots. The African-American-run,

South Central Los Angeles—based company produced ethnically correct playthings long before they were fashionable.

Although Barbie's sales have never substantially flagged, Mattel has been a financial roller coaster. It nearly went broke

in 1974, when the imaginative accounting practices of Ruth Handler and some of her top executives led to indictments against

them for falsifying SEC information, and again in 1984, when the company shifted its focus from toys to electronic games that

nobody wanted to buy. The second time, Michael Milken galloped to the rescue. "I believed in Barbie," Milken told Barbara

Walters in 1993. "I called up the head of Mattel and I told him that I personally would be willing to invest two hundred million

dollars in his company. There's more Barbie dolls in this country than there are people."

The Barbie story is filled with loose ends and loose screws, but unfortunately very few loose lips. In a world as small as

the toy industry, people are discreet about former colleagues because they may have to work with them again. As for welcoming

outsiders, the company has much in common with the Kremlin at the height of the Cold War. To a degree, secrecy is vital in

the toy business: if a rival learns in August of a clever new toy, he or she can steal the idea and have a knock-off in the

stores by Christmas.

Nor am I what Mattel had in mind as its Boswell. Inspired perhaps by Quindlen and Goodman, or, more likely, by fear and a

deadline, I had owned up in my weekly

Newsday

column to having cross-dressed Ken because of antipathy toward his girlfriend. This was years before I gave serious thought

to Barbie's iconic import, but it was not sufficiently far in the past to have escaped the attention of Mattel publicist Donna

Gibbs, who, when I first called her, did not treat me warmly. Miraculously, after a few months, Donna and her colleagues became

gracious, charming, and remarkably accommodating. I was baffled, but took it as a sign to keep—like the entity I was studying—on

my toes. Still, it was hard not to be seduced by the company, especially by its elves—the designers and sculptors, the "rooters

and groomers," as the hair people are called—who really did seem to have a great time playing with their eleven-and-a-half-inch

pals.