Forever Barbie (21 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

Not all of Powell Hopson's suggestions were implemented, but many were—the most significant of which was making not one but

three dolls with varying pigmentation. The series includes Shani, the lead doll, who has a medium-brown complexion; Asha,

who is very light; and Nichelle, who is very dark. In

The Color Complex: The Politics of Skin Color Among African

Americans,

authors Midge Wilson, Kathy Russell, and Ronald Hall argue that skin color plays a part in the formation of social hierarchies

within the African-American community. One of the many studies that the authors cite—mounted, in this case, by Wilson and

two of her students at Chicago's DePaul University—shows how the self-image of black women is sometimes negatively affected

by the darkness of their skin. In this study, eighty participants— black and white, male and female—were asked to examine

photographs of twelve African-American women and describe them. "Regardless of the individual woman's attractiveness," Wilson,

Russell, and Hall write, "the study participants nearly always rated the dark-skinned women as less successful, less happy

in love, less popular, less physically attractive, less physically and emotionally healthy, and less intelligent than their

light-skinned counterparts." They were, however, believed to have a good sense of humor—attributable to what the authors called

"the Whoopi Goldberg effect."

Rather than deny the existence of color bias, Powell Hopson has found that by using dolls with different skin tones in play

therapy, she can help undermine negative stereotypes—or at least determine how they took shape within a specific child's family.

"A child might have the lighter-complexion doll—Asha—taking control or being the leader," Powell Hopson told me. "I'd see

that and try to explore that with her. . . . And then I might see how that dynamic is reflected in her home environment—whether

it's the lightest child feeling ostracized or more valued than her siblings because she's lighter in complexion."

Nor do all families give preference to lightness. "My grandmother, who was very light, used to say, 'You see this color? I'm

not proud of this; this means my mother was raped by the white man,' " said Olmec founder Yla Eason.

Powell Hopson wanted at least one of the Shani series to have short hair— to reflect the way African-American women actually

look. But because of little girls' fascination with "hairplay," the dolls have lengthy locks. Nor was Powell Hopson pleased

that her guidelines for "Positive Play"—activities aimed at mothers to steer children toward greater self-esteem—were not

packaged with the dolls. But otherwise, she was proud of the product and its launch.

"If you didn't know better, you'd think the Powell Hopsons designed it— to Mattel's credit," Yla Eason said. "If I were coming

out into the ethnic market, I'd want to put a black face on my look, to say: 'I'm not exploiting you.' You never saw Jill

Barad's face when they were talking about Shani; you only saw the Powell Hopsons." She added: "But all they really said was,

'Black dolls are good; they help black self-esteem. We've got a book and Mattel's got a black product.' "

Surprisingly, Mattel did not showcase designer Kitty Black Perkins, who, between her sincerity and up-from-Jim-Crow life story,

is very hard not to admire. It has since rectified this by featuring her on a 1994 infomercial that highlights the work of

individual Mattel designers. Black Perkins has come a long way from Spartanburg, South Carolina, where, during her childhood,

segregation loomed. There were "a lot of things that when I look at now I cringe," she told me. "To this day, I don't think

my mother will ever go to a restaurant in South Carolina because she had been discriminated against all this time."

Black Perkins took refuge from the unpleasantness in art class, where her talent, even then, stood out. "I must have been

ten or eleven years old, and I always knew that I was going to do something with my hands, and something creative." Today

Black Perkins has a cosmopolitan lifestyle; she jetted to Milan to work on the series of Benetton Barbies—multiracial dolls

clothed not in Benetton miniatures but garments that evoked the company's "United Colors" feeling. "I give my daughter dolls

of all colors," Black Perkins told me, "because she lives in a world that is a lot of different colors." This, too, is a far

cry from the white dolls of her youth: "I played mostly with the dolls that my mother would bring home that her employers

had given her."

Although even competitors applauded Shani's introduction, the line has not been without minor slipups—among them, in 1992,

the design of Shani's boyfriend, Jamal. "They didn't make Jamal look sweet enough," Eason said. "Ken is just an arm-piece,

an escort—he's not to look sexually threatening or even interested in sex." But with Jamal, "It was like uh-oh, don't come

near

my daughter; I know what you're interested in." Mattel has since shaved off Jamal's David Niven mustache and eliminated what

Ann duCille referred to as his "terribly tacky yellow suit." He now looks more like Eason's Melenik doll and less, said duCille,

"like a pimp."

I interviewed Powell Hopson in her Connecticut office just after the 1993 introduction at Toy Fair of "Soul Train" Shani,

linked to the television dance program. With restraint and diplomacy, Powell Hopson confessed that she would have preferred

a more scholarship-oriented line that year, and a wardrobe without "the hot pants and the high boots and fishnet stockings."

And while both she and her husband thought the idea of using Kente cloth—a traditional African fabric—on the dolls was good,

they felt it might have been done with greater decorum. "He didn't like the fact that it was being used for a brassiere,"

Powell Hopson said. "As a blouse, fine; but not as a brassiere."

The point of this chapter is not for scholars or rival toymakers to snipe at Shani, but to understand why, despite the best

intentions, mainstream manufacturers sometimes produce objects that are less than ideal. Jacob Miles, whose recently established

Cultural Exchange Corporation is best known for its "Hollywood Hounds," anthropomorphic stuffed animals with multiethnic personalities,

thinks that minority-run companies are by definition more in touch with their audience. "I'm an African American," he told

me. "An ethnic consumer making product for the ethnic consumer—making product for myself. Our products become the community's

products—so they're essentially buying from themselves. It's not something coming

to

the community, but something coming

out of

the community."

Miles is no stranger to the toy business; he was an executive at both Kenner and Tonka before striking out on his own. He

remembers a pattern behind the scenes at the big companies: toning down ethnic extremes to avoid alienating the white majority.

"What we've learned as educated blacks is that you can't buy your way out of racism in this country," Eason told me. Even

the late Reginald Lewis, the Harvard-educated chairman of TLC Beatrice and one of the nation's most successful African-American

entrepreneurs, "with his billion-dollar company and his $400 million income and his $12 million penthouse, couldn't stand

on the street in New York and catch a cab easily because he was black." This is why she feels consumers of color won't desert

minority-run corporations; she and her audience are linked by a subtext of slights, often invisible to the white majority.

(In case she's wrong, however, she has entered into a limited financial relationship with Hasbro.)

Regardless of its limitations, Mattel's Shani line is an attempt at inclu-sivity— at making consumers of color part of the

company's imagined "America." Its Dolls of the World Collection, in which diverse cultures are also represented, seems to

have the opposite goal—which brings us back to the Mattel pattern of contradictory messages. Far from authenticity, these

dolls have the theme-park bogusness of the "foreign lands" at Disney's Epcot Center, where the world, a set of dangerous,

polyglot, disease-ridden, poverty-stricken countries, has been sanitized into the "world," a set of safe, monoglot, hygienic,

affluent simulacra. Without jet lag or lost luggage, "international" tourists can purchase souvenirs, sample ethniclike cuisine—

even drink the water. (A human version of Barbie is, in fact, currently featured in a musical at the Orlando theme park. In

it, she and her official friends travel through the "world"—that is, through a set of caricatures of foreign countries.)

To be sure, some of the Dolls of the World are less reductive than others. Malaysian Barbie, which the workers in Mattel's

Malaysian factory helped design, gets high marks for authenticity and attractiveness. Ann duCille actually called it beautiful.

But Jamaican Barbie is another story. "She looks like a mammy," Eason told me. "She's got the head rag and the apron, and

I'm like, 'Why did they pick

that

slice of life?' When they did the Nigerian Barbie at least they made her a regal person." DuCille is blunter: "That's the

one I call the anorexic Aunt Jemima."

The phrase book of "foreign" expressions on Jamaican Barbie's box seems almost calculated to patronize. It includes: "How-yu-du"

(Hello), "A hope yu wi come-a Jamaica!" (I hope you will come to Jamaica!), and "Teck care a yusself, mi fren!" (Take care

of yourself, my friend!). But to place this in perspective, even English Barbie—a blonde with whom American Barbie allegedly

shares a common tongue—is cast in this series as "the other." Her box also features a glossary of

English

words.

There is a common thread in this, and it involves Mattel's coding of an "American" identity for Americans to emulate. Americans

define themselves not just by what they are, but by what they are not: Jamaican, Malaysian, English, Scottish, Italian, Australian—to

name but a few of the officially "alien" Barbies. To be "American" is to lose the

caricatured

ethnicity of the Dolls of the World; yet it is not to lose all ethnicity. In Mattel's "America," as in the one invented by

other parts of the entertainment industry, racial diversity is recognized—even

authorized

—through its visibility. It may be an "easy pluralism," as duCille says, but it is a pluralism nonetheless.

I have to credit Susan Howard, an African-American journalist and Barbie-collector, with pointing this out to me—and with

coining the term "designated friend" for Barbie's first pals of color. When we met for an interview, she showed me a Sun Lovin'

Malibu Christie, Barbie's black friend from the seventies. Howard considers the doll, which has tan lines, to be educational.

"You'd be surprised how many white people don't know that black people tan," she said.

Howard does not hide her hobby; Black Barbie sits like a mascot on her desk at

Newsday,

and she has others—including a 30th Anniversary Special Edition—at home. Far from remembering Barbie with rage, Howard, who

grew up in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and now lives on Long Island, thinks of the doll as "an empowerment tool because she did so

many things and she made me feel good about myself." She adds, "I'm sure that some feminists would balk at that idea."

The "empowerment" had to do with the visibility of blacks among Barbie's first friends. In 1968, Mattel's official "America"

looked a lot like Howard's integrated neighborhood—and seeing even an imperfect reflection of her world gave her a sense of

validation. Unlike Lisa Jones, Howard, in her early thirties,

was

young enough to have played with Christie, who, while far from her twin, resembled her more closely than did white Barbie.

"When you're a kid who basically has no one to play with other than yourself and a few friends, this doll becomes your friend,"

she told me. "You don't know how much it meant to me that Barbie had a friend like Christie. Because that meant, well, Barbie

likes black people. And it may sound silly, but it was important for me to know that Barbie liked someone like me. The proof

was in her 'designated friend.' "

W

hen wrriter Jill Ciment was working on

The Law of Falling Bodies,

a novel set twenty-five years ago in the lower-middle-class southern California suburb where she grew up, she had a hard time

figuring out how her characters should dress. Searching through old issues of

Vogue

was fruitless; the clothes were too chic, representative of a class above the one she sought to depict. But while browsing

through the Rizzoli bookstore in SoHo, where she now lives, she picked up Billy Boy's

Barbie: Her Life and Times

and experienced a breakthrough.

"I needed [the characters] to wear schlocko but hip clothes," she told me. And the illustrated book jogged her memory: there

on its pages were herself and her friends—the "hood" or roughneck crowd, as she describes them. Barbie's pre-1967 face brought

back her own grooming ritual—the heavy black liner and "blue stuff" around the eyes, the white lipstick—a look that was defiant

in its knowing garishness. It was also democratic: "Anyone could get miniskirts and fishnet stockings and see-through plastic

raincoats; they weren't like the high-class fashions of today, which really are impossible to afford. There was always a cheap

ripoff at Zody's or White Front."

In

Taste: The Secret Meaning of Things,

Stephen Bayley tells us that "nothing is as crass and vulgar as instant classification according to hairstyle, clothing and

footwear, yet it is . . . a cruelly accurate analytical form." Because Barbie is a construct of class—as well as a construct

of gender— this crass, vulgar, and accurate investigation cannot be avoided. "When it comes to the meaning of things, there

are no more powerful transmitters than clothes, those quasi-functional devices which, like an inverted fig, put the heart

of the matter in front of the skin," Bayley writes. Yet powerful though the transmissions may be, many Americans deliberately

ignore them.

If you want to make an American twitch nervously and avoid eye contact, raise the issue of social class. To do this is to

invite being misunderstood. One is perceived as either a wild-eyed socialist, directing middle-class attention to the exploited

classes beneath it, or an anxious snob, sneering at others to retain a hold on one's own tenuous position. When forced to

acknowledge class differences, Americans often argue that this country has infinite class mobility, which is, of course, hyperbolic—for

everyone except Barbie. Barbie can not only ascend the social ladder, she can occupy several classes at once.

In the early sixties, Barbie was positioned as a high school baton twirler and prom queen. Yet when Jacqueline Kennedy was

in the White House— and the middle class briefly stopped denying the existence of a class above it—Barbie's trunk contained

all she would need for a term at Mrs. Kennedy's former boarding school in Farmington, Connecticut. In the hierarchy of class,

Barbie had duel citizenship, a status she made even murkier when she donned the flashy, synthetic clothes that inspired Ciment.

To chart Barbie's course as a social mountaineer, we will have to define her peaks and valleys. Sociologists usually carve

society into five classes: upper, upper-middle, middle, lower-middle, and lower. In

Class,

his facetious investigation into social status, however, Paul Fussell advances a more nuanced palate. It has nine classes:

top-out-of-sight (the

Forbes

four hundred), upper, upper-middle, middle, high-proletarian, mid-proletarian, low-proletarian, destitute, and bottom-out-of-sight

(the homeless). While destitute and bottom-out-of-sight are virtually irrelevant to Barbie, her lifestyle is a sort of Chutes

and Ladders game among the other seven.

According to Fussell's guidelines. Barbie began a downward trajectory in 1977. Her "SuperStar" face, with its vapid grin,

sent her plummeting. "You'll notice prole women smile more, and smile wider, than those of the middle and upper classes,"

Fussell writes. "They're enmeshed in the 'have a nice day culture' and are busy effusing a defensive optimism." Likewise,

when Barbie's miniature wool suits gave way to polyester dresses, she sank. "All synthetic fibers are prole," he writes, "partly

because they're cheaper than natural ones, partly because they're not archaic, and partly because they're entirely uniform

and hence boring."

Fussell's tone is one of bemused detachment, a defense against accusations that he may be taking class differences too seriously.

On the rare occasions when the unspeakable is spoken, this tends to be how it is expressed. But particularly in the eighties,

when middle- and upper-middle-class children had to confront the prospect of being worse off economically than their parents,

class slippage became more than a facetious concern. Barbie as a class role model, far more than Barbie as a gender role model,

may, in fact, be the linchpin of many mothers' continued misgivings about her.

After interviewing numerous upper-middle-class, Eastern Establishment women, I can say with certainty that most do not interpret

the doll as an updated Neolithic fertility icon. They view her as a literal representation of a modern woman. Many object

to her on feminist grounds—one hears the familiar "that body is not found in nature" refrain. Then the word

bimbo

arises. But let a woman talk longer—reassuring her that she's not speaking for attribution—and she'll express her deepest

reservation: that "Barbie is cheap," where the whole idea of "cheap" is rooted in social hierarchies and economics.

On a recent HBO special, Roseanne Arnold, who, incidentally, collects Barbies, excoriated what she considered to be Barbie's

middle-class-ness. Why didn't Mattel make, say, "trailer-park Barbie"? But to many upper-middle-class women, all post-1977

Barbies

are

Trailer Park Barbie.

Ironically, given the knee-jerk antagonism to Barbie's body, it is one of her few attributes that doesn't scream "prole."

Her thinness—indicative of an expensive gym membership and possibly a personal trainer—definitely codes her as middle- or

upper-middle-class. In

Distinction,

French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu notes that "working class women . . . are less aware of the 'market' value of beauty and

less inclined to invest . . . sacrifices and money in cultivating their bodies." Likewise, Barbie's swanlike neck elevates

her status. A stumpy neck is a lower-class attribute, Fussell says.

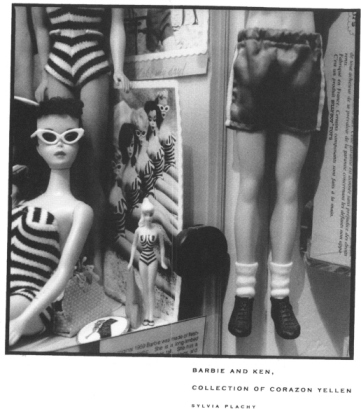

The 1961 Ken, with his lean body, subdued expression, and miniature Brooks Brothers wardrobe, was coded for upper- or upper-middle-class

life. His first decline came in 1969, when Mattel gave him a beetle-browed, smiling face and discontinued his preppie clothes.

Worse, his chest and thighs were beefed up, preventing him from wearing his original togs. No longer could he sport a plausible

dinner jacket; he suffered the indignity of wearing a "Guruvy [sic] Formal" that lowered his class precipitously. True, the

caved-in chest that leading man Jimmy Stewart revealed when he removed his shirt in Hitchcock's 1954

Rear Window

became less dashing in 1977, when George Butler's

Pumping Iron

popularized muscles for men whose professions did not involve heavy lifting. But with his close-set eyes and heightened brawn

Ken remained prole-coded through the 1980s.

Mattel made a decision to smarten him up in 1992—ironically by giving him a face it had originally designed for an updated

version of Midge's fiance, Allan. But even with California's casual sartorial code, Ken never regained his lost standing.

Barbie's initial 1967 face change, by contrast, did not reduce her status. The Twist 'N Turn face did not simper; its expression,

though perky, was still aloof.

In a recent issue of

Allure,

Joan Kron dared to lift the lid on "Secret Beauty Codes." She points a finger at types of "class stigma" that differentiate

a female executive—or a female member of the upper or upper middle class—from, for instance, her secretary. In contrast to

the female investment banker's flat heels, simple clothes, virtual absence of makeup, and classic bob, the "working girl"

will have "high heels, too-short skirt . . . exaggerated makeup, and Big Hair"—characteristics that upper-middle-class mothers

have with dismay observed in Barbie. These mothers have, in fact, singled out best-selling Totally Hair Barbie, with her ankle-length-tresses

and tight, thigh-high minidress, as particularly horrifying; she looks, one observed, like "a professional fourth wife." The

mother's joke veils this concern: While women of uncertain pedigree have since time immemorial married their way into the

upper classes, "mastery of the self-presentation codes—being appropriately glamorous but not ostentatious—is," in Kron's words,

"considered proof that one belongs."

Significantly, there is class differentiation within the Barbie doll line itself; Barbie still maintains the ability to exist

in several classes simultaneously. In 1992, for example, "Madison Avenue" Barbie, dressed and coiffed in the style of Ivana

Trump, was exclusively available for about sixty dollars at FAO Schwarz, Manhattan's tony Fifth Avenue toy emporium. In the

Lionel Kiddie City in Union Square, however, a less prosperous neighborhood, the shelves were stocked with fifteen-dollar

"Rappin' Rockin' Barbie—Yo!" dolls packaged with rhythm-generating boom boxes.

Although Madison Avenue Barbie does, in fact, look like Ivana, the doll seems to have been deliberately coded for parody.

Her pink and green outfit is not made of natural fibers, nor is her flashy pink teddy. Likewise, Mattel designer Carol Spencer's

"Benefit Ball" Barbie—in a splashy blue evening dress with mountains of orange hair—bears a strong resemblance to Georgette

Mosbacher. But her coiffure is so huge and her dress is so flamboyant that she, too, seems to parody Mosbacher, which, as

Mosbacher is not known for understated dressing, is no mean feat. Of the outfits Barbie might wear to lunch at Le Cirque,

Janet Goldblatt's "City Style" Barbie, an off-white Chanel-inspired suit with a small quilted handbag, is the most plausible,

particularly on a doll with shorter hair.

Just as the Native American Barbie does not copy the uniform of a specific tribe but reflects an outsider's interpretation

of Native American identity, the upper-class Barbies reproduce not real upper-class clothing but an outsider's fantasy of

it. They emulate the eighties' rich-person soap-opera look—the look of

Dynasty

and

Dallas

—not the pared-down landed-gentry lifestyle deciphered for the middle classes by, say, Martha Stewart.

Then there are the "Gold Sensation" Barbie and "Crystal" Barbie advertised in magazines such as

Parade.

Priced at $179 and $175 respectively, these "Limited Edition" Barbie dolls can be bought for four "convenient installments"

of $44.75 or $43.75. From their red fingernails to their glittering clothes (the Gold Sensation comes with "a 22 karat, gold

electroplated bracelet"), these dolls are a proletarian daydream of how a rich person would dress. Fussell would, of course,

mock these objects ("Nothing is too ugly or valueless to be . . . 'collected' so long as it is priced high enough," he writes)

but I find them vaguely poignant. In her

Allure

article, Kron observes that it has been many years since, for example, long, brightly painted talons connoted "lady of leisure":

they now imply its opposite, as does every other detail on the dolls.

Seeing them in their wildly excessive getups reminded me of an affecting scene in the movie

Mystic Pizza.

In it, Julia Roberts plays the beautiful daughter of a Portuguese fisherman who dates a patrician young man. When he invites

her home to dinner, she chooses a bare, flashy dress (based perhaps on

Dynasty

notions of upper-class life) that painfully brands her as an outsider. (Class coding is also an issue in Roberts's later movie

Pretty

Woman,

but unlike

Mystic Pizza,

in which Roberts's sister moves up the class ladder by earning a scholarship to Yale,

Pretty Woman

suggests that the sole way a woman can ascend socially is by hooking the right mogul— a distasteful message indeed.)

Although some toys reach across class boundaries, others are clearly targeted to a specific social echelon. Dolls in the Pleasant

Company "American Girls Collection," for instance, are geared to please middle- and upper-middle-class moms. Seemingly dressed

by Laura Ashley, educated by Jean Brodie, and nourished by Martha Stewart, these dolls are almost intimidat-ingly tasteful.

Sold with historical novels (about them) and simulated antiques, they are intended to inculcate in their young owners a fondness

for archaic things—the core, says Fussell, of upper-class taste. Felicity, a doll dressed as an American colonial girl, comes

with a Windsor writing chair, a wooden tea caddy, and a china tea cup—"all she needs to learn the proper tea ceremony." She

must unlearn her skill, however, when her father, in one of the novels, decides to boycott tea to protest George Ill's unfair

tax on it.