Forever Barbie (33 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

Although he owns a vast, valuable hoard, New York-based collector Gene Foote has managed to maintain a sense of self-irony

about his hobby. Foote's principal occupation is musical theater. He directed European productions of such shows as

Sweet Charity, Annie Get Your Gun, Pal Joey, Little Shop

of Horrors,

and

A Chorus Line.

With his Barbies, he also stages production numbers—elaborate dioramas that he has been photographing for a book-in-progress

called

For the Love of a Doll.

"It's literally the story of Barbie," he told me, "but I don't treat her as a product. I treat her as a human being. She's

just a girl named Barbie; yet I give all of the Mattel facts."

Foote grew up in Washington County, Tennessee, in a house without electricity or running water. He still has a trace of a

southern accent and a warm, courtly, old-fashioned manner—which includes referring to Barbie owners of my generation as "Barbie

girls." As a boy, to entertain his younger female cousins, he made paper dolls from figures in the Sears Roebuck catalogue.

"I'd cut out one of the women who had on the girdles or the underwear and glue her on cardboard. Then I would draw clothes

for her and color them and cut them out," he explained. His cousins told him: "You made us Barbies before there were Barbies."

By far the strangest Barbie "collector" that I met was, in fact, an object in Foote's collection. As part of a 1965 ensemble

called "Me 'N' My Doll," Mattel's Skipper doll was issued her own tiny Barbie—barely over an inch in height, with a painted

red swimsuit and yellow hair. And I was struck by the total containment of Barbie's world. It wasn't enough for Skipper to

receive Barbie's sisterly counsel; she, like every other girl, needed a Barbie totem—a thing onto which she could project

her idealized future self—to internalize the Barbie ethos.

For Beauregard Houston-Montgomery, a New York City partygoer and wit-at-large in the style of Quentin Crisp, collecting Barbie

isn't about closed universes or looking inward. It is about looking outward and upward to the heavens. Amassing the dolls,

he said quite seriously, is a "way of dealing with alien abduction."

"People who have been kidnapped start collecting," he continued. "They have collecting manias. Some people collect dirt, like

specimens. Other people collect plants." Or dolls that resemble their captors. To demonstrate this, he showed me his Barbie

Fashion Queen, which, with its bulging eyes, nose defined by two dots, and insectoid face, did seem strikingly similar to

the "aliens" described by alleged abductees. "I was about two, and I was visiting my grandmother on a farm in Missouri," he

said. "And I remember waking up in the night and seeing this thing looking in the window, this creature—looking in at me with

huge eyes. It seemed to float—like, hover— and it kind of glowed. And I remember screaming and yelling for my parents until

it finally disappeared."

Was he actually abducted? Did he plan a hypnotic session with Harvard psychologist John Maeh to find out?

"What do I need to remember being on a spaceship for?" he snapped. "People already think I'm insane; that would only verify

it."

To convince me of his sanity, Houston-Montgomery telephoned his friend, illustrator Mel Odom. On a three-way conference call

late one night, Odom told me that his painting of the 1964 Miss Barbie had a distinct otherworldly quality. "It's the most

E.T. image ever made for children," he told me. "I had friends looking at it, asking, 'Who's the Martian?' "

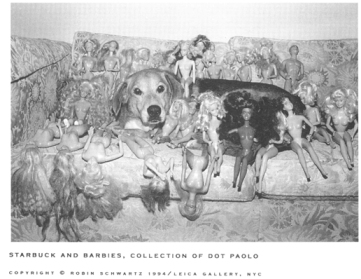

Of course not all collectors accumulate dolls of investment quality. Robin Schwartz, a photographer whose work is in the permanent

collection of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art and whose recent book,

Like Us,

was a collection of primate images, put me in touch with a collector of a wholly other stripe: Dot Paolo, proprietor of the

Rabbet Gallery in New Brunswick, New Jersey. If one anthropomorphizes Barbie, Paolo is the person who adopts the unadoptables—provides

a foster home for the heartbreaking dolls that have been chewed or shorn or battered. Although she is a successful corporate

art consultant, her "collecting" is more merciful than mercenary. "I don't have the dolls standing up with perfect clothes,"

she told me. "What I like is what the children have done to them, the way they cut their hair and drew on their faces."

Schwartz photographed Paolo's dolls—dozens of forlorn, damaged Barbies—with Paolo's dog, Starbuck, who is fifteen and deaf;

Paolo's compassion does not extend only to plastic objects. It is not a comfortable photograph. Even though they are not human,

there is something tragic about the flea-market Barbies; the sad, spent dolls cast away without so much as a glittering G-string.

They will not be fought over at auction or cherished by grown men. But at least they are among their own kind, not condemned

to the landfill, watching coffee grounds and banana peels disintegrate before their nonbiodegradable eyes.

I

f Barbie were merely another global power brand like McDonald's or Coke, ending this book would be simple. One would focus

on what Mattel has in mind for its billion-dollar damsel, as well as on the company's rapid growth. In 1993, it gobbled up

Fisher-Price, a producer of preschool toys, and in 1994 it purchased Kransco, the maker of such classics as the Whamo Frisbee

and the Hula Hoop. Today, it is as large as or larger than the industry's longtime Goliath, Hasbro.

But Barbie's story is, of course, far more than a tale of shareholders' meetings and annual reports. It is a saga of mothers

and daughters, men and women, hope, despair, passion, and the striving after an impossible "American" ideal. Barbie is an

emblem of "femininity," a concept quite different from biological femaleness. Barbie was invented by women for women, and

the wrath brought to bear upon Barbie by some women is perhaps wrath deflected from themselves. For daughters are indoctrinated

into "femininity" by mothers—not by a plastic object. "Even a generous mother," Simone de Beauvoir wrote, "who sincerely seeks

her child's welfare, will as a rule think that it is wiser to make a 'true woman' of her, since society will more readily

accept her if this is done." Barbie permits such "generous" mothers to wash their hands of the taint of "femininity," to blast

Barbie as a "bimbo," even as their conflicting messages and ambivalences etch their way onto their daughters' evolving minds.

Barbie is also a space-age fertility icon, a totem of an ancient matriarchal power. In the dark, primal part of our brains

where we process primitive archetypes, she is Ur-woman. As an icon, she has come to represent not merely "American" women

or consumer capitalist women, but a female principle that defies national, ethnic, and regional boundaries.

Nor is Midge to be overlooked as an archetype. If Barbie is Ur-woman, Midge is Ur-sidekick. The entire female sex can, for

the most part, be divided into Barbies and Midges. From Gilgamesh and Enkidu to Achilles and Patroclus to the Lone Ranger

and Tonto, epic pairings have historically involved men. But by the mid-twentieth century, the convention broadened to include

women. For every Lucy, there began to be an Ethel.

Because of Barbie's archetypal resonance, to mutilate a Barbie doll is not to vandalize a toy; it is to attack a woman. As

evidence, one need merely cite the police investigation of the "Sandusky Slasher," who within six months between 1992 and

1993 cut the breasts and mutilated the crotches of two dozen Barbie dolls at three stores in Sandusky, Ohio—where, incidentally,

Barbie Bazaar

is published. (Sandusky is also the hometown of Sugar Kowalsky, Marilyn Monroe's character in

Some Like It Hot.)

In February 1993, Perkins Township police received an FBI profile of the suspected slasher—a white male between the ages of

sixteen and thirty. He is "an organized and controlled individual who is probably dominated in a relationship with a woman,

possibly his mother," reported the

Chicago

Tribune,

and is "considered harmless by friends." The FBI appears to have treated the crime as if the doll were an actual woman; it

has constructed a psychological profile reminiscent of Hitchcock's Norman Bates. But my hunch is that the assault—like so

much of the art that involves Barbie mutilation—may have been upon Barbie as a construct of femininity rather than Barbie

as an archetypal woman. And if so, the perpetrator might well be female. (I find myself wondering if Andrea Dworkin can account

for her time when the attacks took place.)

Nor has Barbie merely been a crime victim. In one of the more lurid kidnappings of 1993, she was an accessory. Accused Long

Island child abductor John Esposito required a powerful magnet to lure seven-year-old Katie Beers away from a shopping mall

and into a dungeon beneath his house. What was his bait? The Barbie exercise video.

Then there is the "Barbie strategy": a way of gaining attention for one's ideas by linking them to Barbie. Shortly before

the 1992 presidential election, pop culture analyst Greil Marcus wrote an op-ed piece for

The New

York Times

explaining Bill Clinton's "Elvis strategy"—how he grabbed press coverage by associating himself with the King. When President

Bush accused him of promoting "Elvis Economics," Clinton raised a saxophone to his lips and belted out "Heartbreak Hotel"

before the astonished eyes of Arsenio Hall and his television audience. "Slap Elvis on anything and you'll be noticed," Marcus

wrote. "Elvis in a speech is a guaranteed soundbite on the evening news."

In 1992, the American Association of University Women demonstrated that Barbie was a guaranteed soundbite, too. When the group

complained about a Barbie who said, "Math class is tough," the story made page one of

The Washington Post.

Like Clinton with Elvis, the AAUW used Barbie to direct attention to its own agenda—a 1991 study it had commissioned which

showed that girls begin to lose their self-confidence at puberty. At age nine, the girls were assertive and academically self-assured;

but by high school fewer than a third felt that way.

The upshot from the incident—a public discussion of how that age-old toxin "femininity" warps bright, androgynous minds—was,

of course, a good thing. But I couldn't help feeling Barbie got a bum rap. After all, the doll didn't say, "Math class is

tough/or

girls,"

or "Math class is tough; let's study cosmetology." She simply said, "Math class is tough"—which struck me as a call to knuckle

down and master the subject. Would a doll who said "Computers make homework fun" be likely to quake at the sight of an algebra

problem? This underscores another pattern in Barbie's universe. People project fears and prejudices onto her; when a person

talks at length about Barbie, one usually learns more about the speaker than about the doll.

Reinvention is a constant in Barbie's life, but at Mattel as in Ecclesiastes, there is nothing new under the sun. The 1993

Western Stampin' Barbie is a direct knockoff of the 1981 Western Barbie, except that the earlier model's eye winked. Similarly,

Barbie has been pushing homeovestism—the masking of one's cross-gender strivings by decking oneself out like a parody of one's

own gender—in slightly different guises for a decade. Modeled on the mid-eighties Day-to-Night Barbie, the current "We Girls

Can Do Anything" Career Collection dolls are packaged with implicitly "masculine" daytime work outfits and absurd caricatures

of "feminine" evening dresses. The contrast, for instance, between the 1993 Police Officer Barbie's work garb—a natty indigo

uniform with trousers, a necktie, and a long phallic flashlight—and her "glittery" evening frock—a gilded bustier with a gold-flecked

tutu—is particularly striking. No one but a drag queen—or a homeovestite—would be caught dead in it.

In response to tough new environmental laws in Europe, however, Barbie's chemical composition, while still plastic, has changed.

It is no longer exclusively polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which, when incinerated, produces hydrochloric acid, linked to acid

rain. The doll's arms are made from ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA), its torso from acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS), and

its bend-leg armature from polypropylene. Only its outer legs remain PVC—but this, too, is a different formula from that of

the early dolls. In the late eighties, the German government passed a law restricting the amount of plasticizer (a softening

agent) permitted in PVC. German consumer watchdogs worried that if a child accidentally swallowed a toy made of PVC, his or

her stomach acid would extract its plasticizer, leaving behind a hard, dangerous object.

"We tried to argue with them by conducting tests where we had plasti-cized PVC Barbie shoes tied on a tether fed to pigs,"

explained Maki Papavasiliou, Mattel's vice president of corporate environmental affairs. "For weeks on end they would fish

them out and weigh them to demonstrate that there was no weight loss—no plasticizer loss." But the Germans remained unconvinced,

so Mattel complied with the law, making Barbie's legs less flexible than they used to be.

Mattel has also adapted its packaging to comply with European regulations. The display windows in Barbie's European boxes

are no longer made of PVC, and the company has made a commitment to use more recycled materials. The floor, in fact, in Barbie's

three-story town house is liiade of postconsumer recycled ABS.

Although Barbie wasn't sold in Europe until the early sixties, Germany and France are now among Mattel's most important markets.

Likewise, Mattel has recently begun selling Barbies in Japan, instead of issuing Barbie-like teen fashion dolls through a

Japanese franchise. Barbie kicked off her new internationalism in 1990 with the "Barbie Summit," a kiddie United Nations that

took place at New York's Waldorf-Astoria. Its slogan, in English, was "One Child/One World," which was emblazoned in several

languages on the official Summit doll's carton. But one had to question Mattel's phrasing. The translations were not always

literal—the German version, for instance, was

"Fine Welt fur alle Kinder"

—literally "One world for all the children." Yet the Italian translation needlessly preserved the English construction. Thus

"Un bimbo/un mondo"

was boldly displayed on the box.

Despite its economic problems, Eastern Europe is a new frontier for Barbie. Children in Moscow clamor for the doll, and often

have to settle for stout Russian knock-offs with large feet, smudged makeup, and fright-wig hair. Families who can afford

an authentic Barbie often cannot afford authentic clothes; they must sew outfits for the doll. To relieve the shortage, some

American Barbie collectors organized a shipment of dolls to Russia, and even Cher, no fan of Barbie, brought dozens of them

on her recent trip to Armenia, whence her family originated. "I always hated you, Barbie," Cher told

People

magazine, "I always thought you were a blond bimbo, but now I see that you have your uses."

Not all members of the former Soviet empire are welcoming Barbie with glee. In a full-page 1993 article in

Sobesednik,

a Russian pop cultural journal that had, until 1990, been a supplement to the Communist Youth Party newspaper, two waggish

writers joked about Barbie's anatomical deficiencies and high cost—so steep, in fact, that in order to afford her, three families

had to share her: "For a week the American girl will live with Masha; for a week with Dasha; for a week with Kolya." They

describe Barbie as "the plaything of the century" and—racy pun intended—as "the most popular woman for sale in all the world."

One could end here, with Barbie's Eastern exodus, a path obliquely reminiscent of Hitler's annexation of the Sudetenland,

Poland, and Czechoslovakia. But having opened this book with an emblematic spectacle, I had hoped to close with one—perhaps

a snapshot of Teflon felon Ruth Handler restored to her rightful glory, autographing thirty-fifth-anniversary products for

hundreds of fans in the Barbie boutique at Manhattan's FAO Schwarz. Yet the essence of Barbie—what makes her more than a global

power brand—has to do with the way she colonizes the inner lives of children. Thus to des, ribe an official corporate function

would have been to slight Barbie's grass-roots identity.

I was about to abandon the anecdotal approach when I learned that the College Art Association's 1994 meeting was scheduled

to take place at the New York Hilton the same week as the American International Toy Fair. A little over thirty blocks from

the showrooms where Mattel would be hawking its latest Barbies, Erica Rand, a Bates College art historian, was slated to make

a very different Barbie presentation. Rand wasn't interested in the doll per se, but in how it could be subverted for women's

pleasure. Her work had been inspired, she told

Lingua Franca

magazine, by a 1989 photo spread in

On Our Backs,

a lesbian pornographic journal, that featured a Barbie-like doll used as a dildo. Presented as part of a panel cosponsored

by the Gay and Lesbian Caucus, her paper was entitled "The Biggest Closet Ever Sold: Barbie's."