Forever Barbie (15 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

But in 1983, when the home video game market crashed, Mattel crashed with it. Desperate to stay afloat, it began unloading

its subsidiaries— Western Publishing, Circus World, Monogram Models—even its own electronics division. Ironically, all the

companies whose stability was intended to offset the toy world's volatility were undergoing upheavals. And toys— particularly

Barbie—were thriving.

It could be said that Barbie saved Mattel. Lured by her track record of profitability, venture capitalist E. M. Warburg, Pincus

& Company, junk-bond king Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc., and merchant banking firm Riordan & Joseph supplied the toymaker with

$231 million in capital in July 1984. It was, given her penchant for hanging out with celebrities, a classic Barbie moment.

Her white knight at Drexel was none other than Michael Milken himself. The deal, however, was a huge gamble for Mattel's management

and a reflection of its desperate straits. It had to risk losing control of the company to gain the funds to continue operating.

The group was given a 45 percent voting interest in the toymaker; if, however, Mattel couldn't pay dividends on a new preferred

stock held by the investors, each of their shares would inflate to 1.5 votes—giving them a controlling interest of 51 percent.

By December 1984, Mattel had rebounded, reporting an 81 percent increase in its fiscal third-quarter profit. This enabled

it to pay off the dividends it owed on its preferred stock and, in 1985, to float another $100 million in junk bonds.

With Mattel's future resting on Barbie's slight shoulders, the Barbie team, like the warriors in Etheria, fought bitterly

to rebuff her competitors—particularly a "full frontal attack," as Shackelford put it, from a doll called Jem. In the fall

of 1985, Shackelford learned from undercover sources that Hasbro was planning to launch a new rock star fashion doll at Toy

Fair in February. "All we needed to know was the theme," she said. "Within five minutes, we had a war council. Within an hour,

we thought of what we were going to do." By the time Toy Fair rolled around, Mattel brought out an MTV version of Barbie—Barbie

and the Rockers—with greater fanfare than Hasbro had prepared for Jem. Mattel even beat Hasbro at shipping its dolls to stores.

But the thing that really killed Jem, doll experts say, was her size—twelve and a half inches—which made her too tall to wear

Barbie's clothes. "If you're going to go up against General Motors," says doll dealer Joe Blitman, "you'd better be the same

size."

Despite Barbie's constant triumphs in the marketplace, Spear stubbornly refused to place his faith in her. To attempt to reverse

Mattel's fortunes, he launched new product lines—including Captain Power, a gimmicky electronic superhero that responded to

cues in a Mattel-produced television cartoon program. In 1987, when Captain Power fizzled and Mattel reported a $113 million

loss, John W. Ammerman, who had been in charge of its international division, replaced Spear as CEO.

Ammerman began his tenure with a machete; he slashed the payroll by 22 percent and refinanced $110 million of costly junk-bond

debt. Heads rolled both at home and abroad: he closed ten factories—including those in Taiwan, the Philippines, and Paramount,

California, Mattel's last domestic plant—leaving open only nine, all in countries with the lowest labor costs. It was during

this upheaval and the unstable years before—a time that broke or battered other Mattel executives—that Barad flourished. "The

company was going to hell," one executive told

Working Woman,

and Barad "not only survived it, she rose up out of the ashes."

Shackelford resigned in 1988. Rita Rao, who had left when Shackelford (and other people at Shackelford's and Rao's level)

was made a vice president in 1978, returned. Until the dust settled, Barad removed herself from marketing to product development,

a relative backwater. Then in 1988, she returned to lead the Barbie team. Supporters of Barad—and there are legions—suggest

she made her way upward through a combination of brilliance and charm; detractors include guile as well.

In 1988, under Ammerman's guidance, Mattel's financial course did, in fact, reverse. It reported $35.9 million in earnings.

The growth continued in 1989 with earnings of $79.6 million, more than double that of the previous year. Some of this rise

can be attributed to the introduction of Holiday Barbie in 1988, a doll that pushed Mattel's market segmentation strategy

a step farther, testing the waters to see if the mass market would spend more money on a deluxe version of the doll. "My motivation

in doing it was to see if we could break a price barrier," Rita Rao explains. "Barbie pretty much has always been a ten-dollar

doll, and it was kind of deemed an unspoken rule that you couldn't go past that. And I felt that in the long term for the

company we had to . . . break through that barrier. And . . . to do it in a big way." Not only was Holiday Barbie successful,

but "it opened the door for us to do Birthday Barbies and Talking Barbies and other things that were at the higher price point."

In 1989, Barad became president of the girls' and activities toys division; then, in 1990, president of Mattel USA. She was

elected to the board of directors in 1991. Soon she began to be lionized in the press—for her achievements, her youth, her

beauty. Male colleagues were awed by her fluency in the language of clothes. "Her sense of product was exquisite," Tom Kalinske

told me. "I think she still thought like a little girl. She had this way of looking at a hundred different ideas and saying,

'This one won't work because . . .' or 'This one will—and why don't you put a little more hair on it? '"

One year she told Kalinske, " 'We've got to put Barbie in an all-gold lame gown,' " he recalled. "And I said, 'It's a really

expensive fabric. Why can't we just put her in pink again?' " She said, 'Because gold lame* is really the "in" fabric' Well,

it wasn't at that particular moment, but by the time we brought the doll out, it was. Now how the hell do you know that?"

Even Ruth Handler, who does not compliment idly, praises Barad. As she and I thumbed through snapshots of Barad and herself

receiving an award at a United Jewish Appeal function that had taken place shortly before our interview, she called Barad

"terrific" and "smart."

Like She-Ra and the gang from Etheria, who had personal mythologies and wore talismans that represented their magical powers,

Barad created a myth to explain her success and designated a piece of jewelry as its symbol. Each day, on her chic and impeccably

accessorized ensembles, she pins a golden bee. "The bee is an oddity of nature," she explains in her official Mattel bio.

"It shouldn't be able to fly but it does. Every time I see that bee out of the corner of my eye I am reminded to keep pushing

for the impossible."

Given Barad's schedule, booking an interview with her meant "pushing for the impossible." Things kept cropping up—like her

being named, on July 23, 1992, Mattel's CEO, the second-highest-ranking officer in the $1.6 billion company. (She has since

been named COO.) Consequently, in September, after having finally secured an appointment, I was not surprised when she canceled.

Her reason, however, floored me: she had been stung by a bee and was suffering a severe allergic reaction.

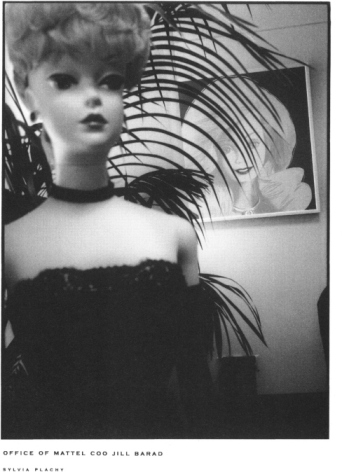

Happily, Barad rallied, and a few days later, with publicist Donna Gibbs adhering to my side like a Secret Service agent,

I traversed the wide blue-carpeted halls of Mattel's executive enclave. Without relinquishing the trappings of corporate power—big

desk, panoramic view—Barad had created a cozy atmosphere within her sprawling office. The place was thick with potted palms.

Upscale collector baby dolls by artist Annette Himsteadt, whose company is owned by Mattel, were sprawled in eerily human

positions on a couch. And refulgent in their sequins, the 1992 Empress Bride and Neptune's Fantasy Barbies—outfitted by Bob

Mackie—twinkled on her desk.

Barad directed me to a conference table whose legs were planted on a thick Chinese carpet. The deep red rug sat atop wall-to-wall

carpeting, and I felt myself sink into it. If Barad had deliberately coded her office to create a sense of softness and femininity,

she couldn't have been more effective. Radiant amid the fronds, she was clad in a yellow silk suit with bold color splashes

that resembled, on closer inspection, jungle animals. She wore shiny yellow slippers that seemed too perfect to have touched

pavement. Nor had she abandoned her trademark bee. I had, of course, seen photos of her, but that did not prepare me for the

perfect hair, seamless manicure, and makeup striking enough for television. She made the Barbies look unkempt.

As Andy Warhol's likeness of Barbie beamed down at us from the wall, Barad told how she had met the artist at a publicity

party for She-Ra, and, after he revealed his fascination with Barbie, commissioned a portrait of the doll—a bold gesture,

it struck me, in keeping with her philosophy of "pushing for the impossible." Inspired, I, too, decided to push, intrepidly

asking if, as one of the country's top female executives, she defined herself as a feminist.

"No," she said in a cool voice. "The fact is, I really don't know what that means. There are negative implications and positive

implications. I'm very female. And I believe there are many dimensions to being a woman—and in my life I have been blessed

with experiencing so many of those dimensions, whether it's being a mother, being a wife, being a friend, being an executive.

Being so much. And I want kids to be able to realize all the different sides of being a woman too.

"I've been able to do that through toys," she continued. "Baby dolls teaching mothering and nurturing—the soft tender moments.

Barbie saying, 'What's it gonna be like when I grow up?' Or Princess saying, 'I'll protect you.' Or the Heart Family—the whole

family situation. It was very much not just a belief in me—but in all the people here in girls' toys—that we were going to

explore all the parts of being a girl."

Barad shares with Ruth Handler the ability to disarm an interlocutor. I won't say our interview was exactly a pajama party,

but something about that doll-packed room lent itself to girl talk. I found myself experiencing ancient feelings that I thought

I had left behind in high school—a consciousness of myself as an owlish drudge dutifully recording, for the minutes of a club

meeting, the wisdom of the homecoming queen. I was shaken by the terrible power of childhood archetypes. I felt like

Midge.

Soon we were agreeing passionately that Barbie was "forever," as an icon, anyway. But I wondered if her sales could sustain

their phenomenal growth. Was there a saturation point? In 1992, the average American girl owned seven Barbies; would twenty

soon be the norm?

Barad likened a child's interest in Barbies to a woman's interest in clothes. "I don't know about you," she said, glancing

at my outfit so disconcertingly that I checked to make sure I hadn't spilled something on it, "but I would imagine every year

you buy something to put in your wardrobe that's new—that makes you feel like it's a fresh year, or it's the beginning of

a season, or you have an event that you didn't have before." I nodded. Kids are the same, she feels. "They really do go on

to what's the latest, what's new, what's exciting."

I asked her if she viewed children as noble savages or beasts to be civilized. She rejected both extremes and talked about

"magic . . . that keeps the child in all of us alive." I asked why no rival doll had ever successfully challenged Barbie—as

if I, Midge, didn't know. "I think you've got heritage going," she explained. "We've got the marketing and product design

talent. There really is no hole that somebody's going to come in and fill. And anytime someone comes after us frankly only

makes us smarter and better. You've got to stay on your toes."

I lumbered flat-footedly out of the interview, wallowing in my Midge-hood. Something Camille Paglia told me sprang to mind:

"Barbie truly is one of the dominant sexual personae of our time." What did it mean, I wondered, to identify with the personae

of the supporting cast? If Barbie were Ur-woman, did that make me Ur-sidekick?

Barad has grumbled about accusations that she used her looks to advance herself—"I've seen very handsome men in business,"

she told the

Los

Angeles Times.

"Does anyone ever say it's because he was so handsome that he got ahead?"—but after listening to her polished, diplomatic

responses, I was sure that she hadn't. It did, however, cross my mind that she may have used her looks to camouflage her nonreliance

on them—and, so briefly as to be almost unnoticeable, Day-to-Night Barbie flashed before my eyes.

But even with her record sales, the Barbie of the late eighties was not the vibrant virago of the early eighties. "We Girls

Can Do Anything" gave way to "We're into Barbie," a slogan that suggests turning inward, away from active engagement with

the world. "The viewpoint of people changed," Barbara Lui explained, "and the 'mommy track' came on, and women didn't believe

anymore that they could do anything. We're in an era—perhaps we're leaving it now—where people did not give themselves goals

that were as tough."