Forgotten Wars (84 page)

Authors: Tim Harper,Christopher Bayly

This was the quiet beginning of a second wave of independence struggle, one that would carry on beyond the formal transfer of power: the decolonization of the mind. The impact of this movement stretched beyond print to performance. In these years the theatre took a scripted form and the Malay cinema became a new vehicle for exploring social and national agendas. It was the invisible city brought to life; the life of the streets and the urban villages featured heavily in the new films. Most dramatically of all, the Malay cinema became a new vehicle for exploring social and political themes. It reached beyond its language stream and built on the hybrid, polyglot style of the Malay opera. Malay movies spun tales of the wartime underground and brought

the urban fantasy of the Worlds, the entertainment parks, to life: indeed, the cabaret was a staple backdrop for early social dramas. The Shaw brothers’ film

Nighttime in Singapore

, directed by B. S. Raghans – a graduate of the Indian National Army’s wartime propaganda school in Penang – had settings at the Padang and the New World. In

Seruan Merdeka

, Bachtiar Effendi – a leading ‘culture warrior’ for the Japanese during the war – played a police informer.

162

The Shaw brothers and Loke Wan Tho ran rival racing stables, and rival film studios with their own small galaxies of stars. Politics retreated into popular culture. But this urban world was beginning to vanish almost at the moment it came to life on the silver screen. Ever since the anarchic days of the British Military Administration, the authorities had been cleaning up the streets. After 1948 the uniform flats of the Singapore Improvement Trust would remap dramatically the urban landscape of Singapore. It was an ambitious programme of urban regeneration, but it was executed in much the same way as the resettlement of squatters on the peninsula, as an emergency measure, and, for much the same reasons, as a strategy of social control.

163

The cosmopolitan world of the village-city – which had moulded Malaya’s politics for a generation – began to recede.

The generation of 1950, born into a world of radically expanding horizons, came of age in a time of shrinking political opportunities. Keris Mas, in his famous story ‘A would-be leader from Kuala Semantan’, captured one of central political dilemmas of his generation. In it a young radical, Hasan, confides his doubts as to whether or not to join the struggle in the jungle.

He hated violence, yet violence was everywhere, inside the jungle and out. He loved freedom, yet he was pursued by circumstances which imposed upon him and his society. He was committed to only one thing, truth. And a man without freedom has no way of obtaining truth.

‘Perhaps I am a coward!’ – once more the explosion of Hasan’s thoughts shattered the stillness of the night.

Perhaps he’s a coward… the explosion reverberated inside my head.

‘Is it cowardly to hate violence?’ asked Hasan finally. The words vanished into the night.

I had no conclusion of my own with which to reply.

Kuala Semantan, in Pahang, was a centre of MCP support among the Malays. In 1949, for a brief moment, Malay support for the insurrection seemed to be growing and party propaganda attacked the ‘white man’ instead of the capitalist and promised

Merdeka

.

164

Villages along the Pahang river, around Temerloh, were dangerous badlands, and infused with the memory of the heroes of the first British conquest. This was the worst nightmare of the British. For the first time a recording of the voice of a Malay sultan, the ruler of Pahang, was broadcast to calm the area.

165

On 21 May a new regiment of the MNLA was formed: the 10th Regiment, under the command of Abdullah C. D., as political commissar. The Malay radicals who had taken to the jungle rallied under its banner. It was seen as a major triumph by the Party: a goal ‘realised for the first time in the twenty years of Malaya’s revolutionary struggle… This solid fact has also smashed to smithereens all those anti-revolutionary arguments concerning the backwardness of Malayan peasants.’

166

Abdullah C. D. was ordered by Chin Peng to mobilize recruits, and managed to raise nearly 500 Malays by early 1950. The British need for information was now ‘desperate’: ‘the reign of terror established by Malay banditry’, it was reported from the area, ‘is quite extraordinary’: they even took the unprecedented step of paying money to those Malays whose property was destroyed for helping the British.

167

A camp near Jerantut was broken up by military action – led by Chinese ex-Force 136 personnel – and the remnants were dispersed in much smaller numbers. It was a serious setback. The alliance of the Malay peasant and the Chinese worker failed just at the time the feudalists and the capitalists, in the shape of UMNO and the MCA, were coming together. There were other centres, in Jenderam in Selangor, the site of the Peasants’ Congress in May 1948, where at least eighteen villagers joined the MNLA, eleven of whom died in the jungle.

168

The 10th Regiment remained a demon to haunt the British.

But the MNLA was locked in the jungle fastness, and coming to terms with the fact that its fight would drag on for many years. ‘Throughout the history of the world’, it warned, ‘one can never find a simple and easy revolutionary struggle. So revolutionary wars, in particular, must necessarily be full of difficulties, obstructions and dangers.’

169

By the end of 1949, the number of incidents began to rise

again. As Chin Peng later acknowledged: ‘If I had to pick a high point in our military campaign, I suppose it would be around this time. But it would be a high point without euphoria and it would be short lived.’ The MNLA turned increasingly towards smaller-scale operations against remote rural targets. With reinforcements from Johore, the Pahang guerrillas launched exploratory raids on isolated police stations. But even this strength was insufficient to make an impact on fixed positions.

170

There were some dramatic incidents, but the MCP never gained the initiative in the ‘shooting war’. Its defeats and reverses in 1948 and 1949 proved fatal. The diminishing food supplies meant that its units were steadily broken into ever smaller contingents. As the effects of resettlement began to bite, conditions in the forest deteriorated sharply. The Party leadership’s core strategic assumption was that the squatters would swell the ranks of the revolution. But already relations between the party and the rural people had deteriorated from what they had been during the war. Then, the MPAJA had acted as protectors of communities from the Japanese. They enabled them to eke out a living in the face of shortages and sudden violence. Chin Peng, for one, had assumed that the forced movement of people by the British would fail, just as similar schemes by the Japanese had failed. The central strategic assumption of the revolution was that the villages would rise in resistance to the British. But the MNLA could offer them little protection from an equally tenacious and better-equipped regime. Peasant resistance was futile, the Malayan revolution foundered on a false premise. As the Emergency dragged on, the communists became an increasing liability to their most natural supporters, and there was little prospect that this burden could be lifted. The British watched the borders closely, and despite their propaganda to the contrary, there was virtually no infiltration in support of the MCP by land or sea. Chin Peng was in contact with the Chinese Communist Party by a secret postal service in code. Some cadres who were suffering from tuberculosis were sent to China for medical treatment; the expectation was that they could brief their Chinese comrades, receive instruction and then return to Malaya. But none made their way back until the late 1950s. The Malayan revolution – unlike the revolution in Vietnam – had to fall back entirely on its internal resources, and had already begun to eat its own.

The Party leadership was now facing open criticism. Two critics in the southern leadership sparked what became known as the ‘South Johore incident’. Siew Lau was a schoolteacher and intellectual. In 1949 he produced a pamphlet, ‘The keynote of the Malayan revolution’. He argued that the Party had misunderstood and misapplied Mao’s tenets of ‘New Democracy’. They had not built up a wide enough coalition of support across all communities. The lack of Malay support had ‘doomed the revolution from the start’. There was no coherent programme of land distribution of the peasantry. He attacked the ‘buffalo communists’ on the Central Committee, and his polemic came with a call for elections for a new committee. Siew Lau went as far as to hold a meeting in November to discuss his ideas. The Party leadership demanded that he recant. Siew Lau tried to escape with his wife and some followers to Sumatra, but was caught and executed. ‘Siew Lau’, the leadership pronounced, ‘had proved himself impossible.’ Another figure involved was Lam Swee, a former vice-president of the Singapore Federation of Trade Unions. Chin Peng later argued that his alienation was as much the consequence of ambition as of doctrinal dissent. The following year Lam Swee became one of the most high-profile surrenders to the British. Both these incidents were the subject of early attempts at black propaganda by the British against the Party.

171

But ordinary rank-and-file members were voicing similar complaints at the arrogance and privileges of the high command, leaders of which ordinary Party members had only the haziest notion. The party’s once formidable apparatus for political education went into steep decline. As one early defector put it: ‘I was treated like a coolie.’

172

By February 1953 986 communists had taken advantage of amnesty terms. In such circumstances, the mood of paranoia and betrayal that had so dogged the Party since the war became deeper still.

The last year of a troubled decade ended with the beginning of a series of long marches for the Malayan Communist Party. It drew on legends of the Japanese war to sustain morale. Within the jungle, songs and commemorations kept the dream alive, such as the marking of the legendary 1 September 1942 Batu Caves massacre, with a ‘91’ oath to reaffirm loyalty. It was a morality tale of strength in adversity that encouraged a belief in the inevitability of victory, a faith that

sustained the MNLA, even when it suffered severe reverses.

173

But its leaders knew that there was no road back: it was too late to break up the army and return to civilian life. They pressed ahead, hoping that some sudden shift in conditions within Malaya would occur, that a new wave of labour unrest might paralyse the country and allow them to take over. But neither this nor a dramatic widening of Malay support materialized. The Party’s 1 October 1951 directives – the product of two months of self-criticism by Chin Peng and his small politburo – openly acknowledged that the initial campaign of terror, the slashing of rubber trees and the destruction of identification cards, had hit hardest the Party’s own sympathizers. The MCP still looked to rebuild its political base, to attempt to recapture influence in the towns and revive the united front. But its fighting units began to withdraw into the deep jungle interior. Chin Peng and his dwindling headquarters was harassed from near Mentekab through a series of camps northwards to Raub, then to the Cameron Highlands and eventually, in the last weeks of 1953, compromised by betrayals from comrades in the pay of the Special Branch, he passed over the Thai border. The area around the Betong Salient remained the redoubt of the Malayan revolution until December 1989, when a peace treaty was finally signed in the Thai town of Haadyai. ‘I never admit that’s a failure’, Chin Peng said later. ‘It’s a temporary setback…’ But by this point guerrilla morale was deteriorating in many places, and more defections occurred. From this position the MCP could prolong the war indefinitely, but it could not win it. ‘I don’t think there was any opportunity of our success,’ reflected Chin Peng. ‘Without foreign aid, we could not defeat the British army, even if we expanded our forces to 10,000… the most was to continue to carry out the guerrilla warfare.’ The Party was now fighting for honour and for posterity, awaiting a general Asian uprising that would never come.

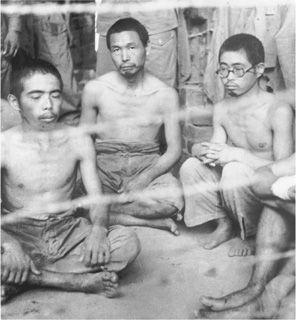

Surrendered Japanese troops in Burma, August 1945