Founders' Son: A Life of Abraham Lincoln (28 page)

Read Founders' Son: A Life of Abraham Lincoln Online

Authors: Richard Brookhiser

Lincoln’s favorite poet was Lord Byron, whose dark moods matched his own. Portrait by Thomas Philips. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

Artemus Ward. Lincoln read Ward and other humorists aloud to his cabinet. C

OURTESY OF THE

H

OUSE

D

IVIDED

P

ROJECT AT

D

ICKINSON

C

OLLEGE

Lincoln’s favorite play was

Macbeth

. He read a scene from it after the fall of Richmond.

The Weird Sisters

, by Henry Fuseli. R

OYAL

S

HAKESPEARE

C

OMPANY

C

OLLECTION

/T

HE

B

RIDGEMAN

A

RT

L

IBRARY

Sarah Bush Lincoln, beloved stepmother, encouraged Lincoln’s reading as a boy and feared for his life after he was elected president. N

ATIONAL

A

RCHIVES PHOTO

306-PSD-58-14438

Mary Todd Lincoln, wife, shared Lincoln’s love of politics and poetry. They also shared difficult temperaments. P

HOTOGRAPH BY

M

ATHEW

B. B

RADY

. © CORBIS

Eliza Gurney, Quaker, prayed in the White House that Lincoln might be “strengthened and refreshed” by the river of life. C

OURTESY OF THE

H

OUSE

D

IVIDED

P

ROJECT AT

D

ICKINSON

C

OLLEGE

Lincoln dismissed John Brown as a zealot and a failure.

Tragic Prelude

, by John Steuart Curry. K

ANSAS

S

TATE

H

ISTORICAL

S

OCIETY

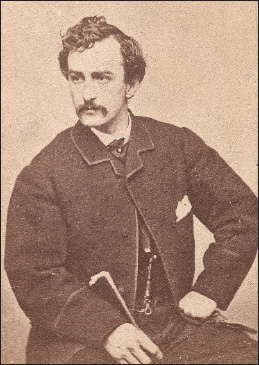

John Wilkes Booth decided to kill Lincoln after he called for “nigger citizenship” (Booth’s words). C

HICAGO

H

ISTORY

M

USEUM

Lincoln reading the Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet. This painting was presented to Congress on Lincoln’s birthday, 1878.

First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln

, by Francis Bicknell Carpenter. US S

ENATE

C

OLLECTION

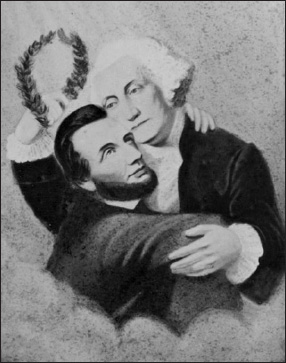

Icons together.

Washington and Lincoln, Apotheosis

. L

IBRARY OF

C

ONGRESS

Lincoln claimed repeatedly that his political rivals rejected the Declaration; they wanted to “cancel and

tear [it] to pieces,” as he had put it in his Peoria speech. Very few actually attacked it outright (that was to come), but there were many who reinterpreted it. Perhaps Jefferson’s assertion of equality was only racial. Stephen Douglas had argued at the debate at Jonesboro that the equality mentioned in the Declaration applied only to whites, not to Negroes, Indians, Fijians, or Malays. Or perhaps the assertion of equality was merely political. Eleven months after the Cooper Union speech, Jefferson Davis, leaving the US Senate because his state, Mississippi, had seceded, would argue that the equality mentioned in the Declaration applied only to citizens. “The communities” of America “were declaring their independence” in 1776 and stating that all “men of

the political community” could aspire to any office. They were laying out the rules of a game in which slaves were not players.