From the Forest (34 page)

Authors: Sara Maitland

The bike slithered on the icy track and the moon cast lumpy shadows, making it difficult to judge the best path, but he did hurry as much as he could. After a noisy while he saw the yellow lights from the office and the white and red lights from the gathering cars. He swung his quad into the car park, circled once and pulled up next to a blue pick-up. As he switched the engine off and there was the sudden stillness between his legs, he knew. He knew absolutely what had happened and he was both angry and frightened.

In the shed they called the office there was a lot of coming and going. He stood with his back against the wall and watched the hullabaloo. His boss was sitting at the desk looking worried; there were four policemen, anxiously trying to get a decent signal; there were three walkers, rather over-elaborately kitted out; there were half a dozen folk from the village and a couple from the farms, already – and there would be more of both soon as the word spread. There was a conspicuous shortage of the forestry workers – Iain’s stag night was taking place over sixty miles away. In a chair in the middle of the office there was a hideous heap of blubber and peroxide blubbering. It was the child’s grandmother. His headache thumped at the sight of her. He closed his eyes. It was all her fault.

She was ten years old. She was wearing pink trainers and a red anorak. She had been missing since about two o’clock, her grandmother thought. She had almost certainly not left the forest. Of course she would be all right, but frightened and very cold. They should find her. Not wait till the morning.

His boss got up and pinned a map to the wall; took a felt-tipped pen; started marking circles, looking at his motley and inadequate forces, trying to deploy them sensibly, where there was little sense.

He forced himself to speak through the thudding of his headache. He’d go up Carsfrae, he said, up to the loch, should he? He knew that best.

She couldn’t have walked that far, could she, surely? Not if she was alone. If she were alone. The bulk of the grandmother wailed. The older of the policemen looked up sharply, glanced around, his eye pausing speculatively.

He pushed himself stiffly off the wall. His boss nodded at him, relieved that someone was doing something vaguely useful. He went out again into the night.

He took his quad up through the trees. Under their cover the forest was very dark, infinite pools of blackness retreating uncowed before his headlights. After about twenty minutes’ riding he stopped at the loch side. Out from under the trees it was much brighter; around the rough shore the water was frozen, glistening in the moonlight; but out towards the middle it was as black as the forest had been. A sudden fierce flit of white overhead was a barn owl on the hunt. The trees crawled up and around both sides of the water and then petered out. At the top end of loch it had proved too boggy even for plantation and the glen ran up into the hills as open rough grass and loose scattered rocks; the moon made enough light out there to see the shape of the hill line.

He switched his engine off and the silence flowed down from the heights. Behind him the trees moaned and creaked softly. He listened, listened to the nothing of the night. Then he unstrapped the rifle, slid it out of its canvas tube and loaded it. Carrying it broken over his forearm, he left the quad at the end of the track and very quietly turned and began to walk up the western edge of the loch. He knew where he was going. Where the Menzell Burn cut down along the forest edge there was a small fall, frozen into silence now, and the channel curved away there and had carved out a peninsula of broken rock. Near the water it was thick with ferns, and in summertime with dragonflies. Behind this was a rock overhang, a small cave. There was its lair.

Three years ago he had taken sick with a fever. Early one morning the two of them – a man, all beard and thick glasses; a woman, skinny with a steel peg in her lower lip and a wild intensity in her eyes – had come to his cottage.

They told him they had stolen a wolf from a zoo and wanted to set it free. But now they had got lost; their van was stuck in some mud ruts quarter of a mile away; they needed his help.

He would have told them to get lost. It was no concern of his. But Ken and Davie arrived, crashing, shouting, hefting his headache up on the muscle of their din. He signed to the two strangers to keep quiet and went out and ran the boys off. He came back into the cottage smiling, and then it was too late. He was committed.

The three of them walked through the wood to the van. The wolf was in the back, mangy, desperate, sad. He could see the sadness, deep in the green eyes that stared without forgiveness, without kindness, without engagement. The beast was restless, turning and turning in the confines of the metal box; it was as lean and strong and fierce as his headache. It was pacing round and round, beautiful and wild.

It was all folly; it was the fever, the madness of the fever and the headache and the green eyes and the sadness. With crafty skill he had lured the wolf out of the van and into the back of his Land Rover. He had pushed the van out of the mud for them and sent them on their way. Then he had taken the Land Rover up to Carsfrae and set the wolf loose. He had gone home to his bed and woken two days later uncertain if it were true or dream. Dream, hallucination, delirium. It was true.

Now as he crept up the loch side in the icy moonlight he was fierce with rage. A stupid child, a little fat spoiled poodle dragged into the forest by her foolish grandmother, ignorant, arrogant, flaunting her so-called sweetness, luring men to evil thoughts, tugging, tugging at his chest. Stupid old woman, fat and flubbery in the chair, wailing. Stupid little girl who should have stayed in town and left him alone. Left the beautiful wolf alone and free on the hillside; the wolf who hunted alone, who struggled against the world. Stupid little brat. Stupid. Stupid. Dangerous idiots. Pink sneakers and a wretched whiny voice.

But even in his rage he was silent, slipping through the trees, careful, deft in the shadows.

Beyond the end of the faint path he had followed, up where the Menzell Burn, frozen into silence, cut down along the forest edge, he found them. The little chubby girl with her clothes torn and her soft belly sticking out under her red jacket, terrified into stillness, petrified, unable to move or shout, was pressed up against a huge boulder left there by a passing glacier a very long time ago. She could not retreat any further and she could not take her eyes off the wolf.

The wolf was three metres away, watching her, crouching, tail and belly low, perfectly attentive. In the moonlight he could see that it was scrawny, too thin and desperate with hunger and grief. The cape of hair on its shoulders, which should have been heavy and luxuriant, was thin and matted into rats’ tails. There was terror and sadness in it.

He paused under the shadow of the last tree. He could see that at any moment the child’s fear would break out and she would turn to run. She was too stupid and ignorant to know that wolves prefer to attack from behind. When she turned it would pounce. He smiled. Waiting and watching.

Its claws would rip off the silly jacket; the weight of its leap would bowl her over; the fangs would sink into her flanks, and then, when she was down, into her neck. The wolf would be well fed for once, would slink back into the rocks around its cave and lurk there until the winter was over and there was easier ground prey and it would live another wild season, free and beautiful. And he could go home to his bed and no one would ever know.

When he looked at the wolf his headache eased. The wolf was beautiful. The wolf loved him because he had set it free.

All he had to do was nothing. Just wait. She would crack, run, scream. The wolf would kill. Serve the little bitch right – that would teach them to avoid the forest and stick to the paths and leave him in peace; not come tormenting and tempting him. They would never know he had been here, that he had found her, that he had seen anything.

But they would search until they found her bones and then they would hunt the wolf, and there would be weeks of noise and coming and going and being and doing in the forest and there would be no peace. No peace for the wolf. No peace for him. They were not free. They were not wild.

He could sense the tension in the child and in the wolf. He waited as long as he could. He watched her as the wolf watched her. He knew she had not seen him and she was ready to break. Then he snapped up the rifle barrel, raising it in a single movement. The noise made the wolf turn and stare straight at him. He saw its eyes, filled with sadness. He shot it neatly in the dark space between the two green lights.

This is what a wood cutter has to do when a girl child is endangered by a wolf.

He did not want to touch her. She made him sick. But he picked her up and carried her back through the trees to the quad. He lifted her onto the saddle and, swinging up behind her, settled her between his legs. He rode more slowly going down than coming up. He did not speak a single word to her.

He led the child in by her hand, offering no comfort. The office was still a puddle of light. His boss was sitting at his desk with a phone in his hand. One policeman was standing by the door, his cap off and a clipboard in his hand. The grandmother was still a lump of slobbery mess on the chair. Everyone else was out in the forest.

The grandmother started screaming – did he hurt you? What did he do to you? Did he? Are you? The child started snivelling. His headache started thumping.

After he had answered all their questions, they let him go. Dawn was breaking grey and grim. The moon had set. The outline of the trees was pulling away from the dark sky, coming towards him. It was terribly cold. He rode back up to Carsfrae and walked once more up to where the Menzell Burn cut down along the forest edge. The ground was frozen too hard for him to bury the wolf, so after a struggle he broke the ice and threw the body into the loch.

Then he went home and hung himself. They did not find him for eleven days.

He was the wolf.

10

December

The Purgatory Wood

O

n Christmas Eve I went into the Purgatory Wood.

We were in the middle of a freakish cold snap. Western Galloway is famous for its mild wet climate and we are ill equipped for snow, but December of 2010 was one of the coldest on record and the whole country was locked down under snow and ice. By Christmas Eve it had been over a week since my thermometer had registered a daily maximum temperature above freezing, and I had been six days without running water, dependent on the good will of my neighbours and a daily delivery of a 25-litre flagon on the back of a quad bike. Below the house the river was frozen so hard that I could see the paw tracks of drama: a fox pursuing a rabbit straight across the water.

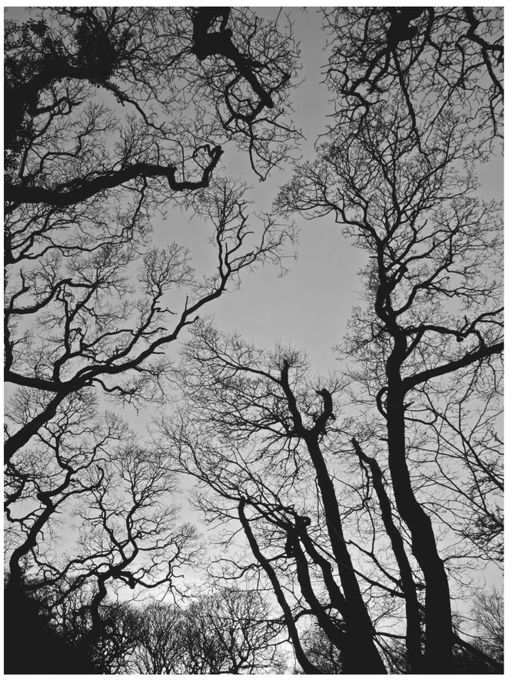

Nonetheless, it was bright and sunny; it was sunny throughout the whole week, a bright cold sun shining in a bright blue sky and catching the snow into sparks of diamond. Three days before, I had woken at dawn to watch the lunar eclipse: the moon a dark shadowy red against a navy blue sky, while on the other side of the valley the still invisible but rising sun turned the sky pale gold and eggshell blue. On Christmas Eve it was very cold; the snow, which had mainly fallen over a week before, was – untouched by any thaw – still white and fluffy wherever it had not been trodden on; the air was sparkling and crisp and there was no wind.

The Purgatory Wood is a patch of privately owned commercial forestry, which fills in between Arecleoch and Kilgallioch forests, two larger stretches of Forestry Commission plantation, making it a part of the vast (too vast) Galloway Forest. At three hundred square miles, the Galloway Forest Park is the largest in Britain. And while wide swathes of the park are not under plantation at all, because they contain rich ancient woodland or seriously wild hill country, the forestry continues well beyond the boundaries of the park. At all times of year the Purgatory Wood is a sinister and unattractive place, as such plantations tend to be. Typically, it is planted predominantly with non-native spruce, and in winter spruce is particularly flat coloured: monochrome monoculture at its most monotonous. Although there are occasional stands of larch, little looks deader than larch with its needles off – the thin branches and proliferation of twigs make a dry brittle outline like tiny bird bones. The wood is very densely planted and therefore it is well-nigh impossible to walk between the trees; in places, even my dog struggles to force herself through branches that come right down to the ground, so any walker is effectively confined to the track. There are the occasional standard treeless breaks, with drainage ditches dug straight down the centre, but they tend to be boggy here, overgrown with rough tussocky grass, although occasionally I could see down them and out onto the cold white hills. The owner of the wood – an anonymous ‘trust’ – has, moreover, done a strange thing: it has erected neat little wooden notice boards which give the names of the farmsteads destroyed to plant the trees: Glenkitten, Miltim, Craigenlee. You walk among dead-feeling trees and dispossessed ghosts.