From the Forest (31 page)

Authors: Sara Maitland

When she was gone I felt chilled to the bone and, for the first time in my life, old. But I fired myself up on wrath and waited for her tom cat to come prowling round the Folly. As the evening came and the sweetness of bird song faded into soft dusk I heard him come through the trees. He stood below the window and in a strong and confident tenor, he sang my song.

Rapunzel, Rapunzel

Let down your long hair.

The gall of it. I taught him a surprise lesson in good manners and humility. He limped away back into the forest, blind and defeated. I did not care. I felt a warm thrill of triumph and then a great long-lasting weariness.

I do not know why I behaved that way. I do not know. There could have been a different and prettier story – for me I mean. There was, I have learned, a prettier ending for them. They found each other in the end despite my best efforts. She had her twins, she cured his eyes and they lived happily ever after. I do not know why I acted like her birth parents – I stole her hair and I sold my love too cheap, for a moment of rage, for the short-lived flower of spiteful anger. I was a fool.

I still keep her hair. Though the flowers I wove into it have faded and crumbled, it is still lovely.

In my dreams I am still brushing her hair, brushing and braiding and binding her hair – her lovely, tendrilling, conker-coloured, wanton hair. Brushing and braiding and binding. It is still the colour of beech leaves in autumn, with reds and golds in it like Slender St John’s Wort in high summer and deep gilt like Bog Asphodel on the moors. It still twines like honeysuckle around my fingers, my hands, my arms, my heart. Brushing and braiding and binding her hair. Singing as I run the brush through it:

Rapunzel, Rapunzel

Let down your long hair.

Bright morning,

The birds all sing,

Rapunzel, Rapunzel

I’m brushing your hair.

One, two, three

Like the Holy Trinity,

Rapunzel, Rapunzel,

I’m braiding your hair.

I keep it, all twenty glorious ells of it, coiled like a snake in the Folly in the forest.

9

November

Kielder Forest

I

t was an unusually bright and pleasant morning for November. Adam and I sat over our coffee watching the birds on the bird feeders in the garden of the Bed and Breakfast where we had spent the night.

1

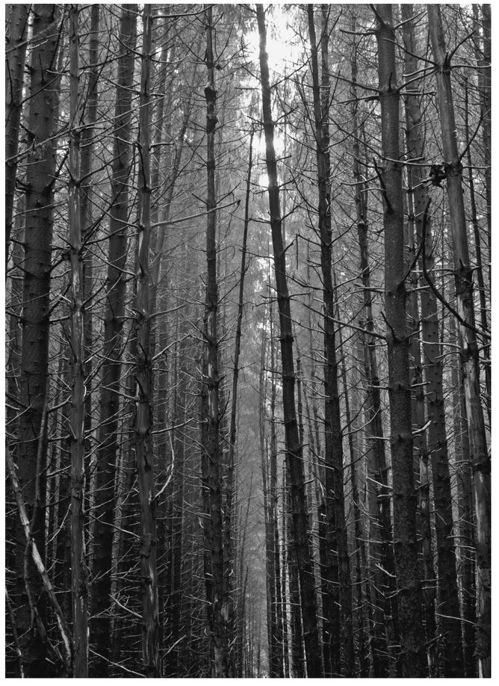

The dense plantation of conifers at the eastern end of Kielder Forest rose above us behind the house, and looking north, we could see over the river and across the wide valley to more dark close-planted trees. We were waiting contentedly for Max McLaughlin of the Forestry Commission to come and collect us for a tour of the forest.

Between the house and the river was the road; we had come in from the east on it, and it continued westward, along the side of the reservoir and into the heart of the forest. It felt just like the beginning of a fairy story. So many of them start with the hero or heroine leaving home on the edge of the woods and setting out on a road through a forest, to meet new people and learn new things and have an adventure.

The day before, Adam and I had come down the lovely A68 from Edinburgh and crossed into England at Carter’s Bar, with the vast views along the western shoulders of the Cheviots. This is one of the emptiest places in England: isolated high hills with the occasional patch of woodland along the river valleys. Traditionally, this vast swathe of wilderness between the Tyne Valley and the Scottish Lowlands was unproductive and under-populated, mainly managed for grouse shooting and sheep farming: it is desolate, fierce country.

Historically too it is a wild place – the Roman legions encountered so much trouble and unrest in this region that it led to Roman Empire’s first retreat: they pulled back from the Antonine Wall (which ran approximately from Edinburgh and Glasgow) in AD 162 and constructed and heavily fortified the new Hadrian’s Wall, to the south of us now. Later the area was disrupted by continual armed forays between England and Scotland, along a disputed unsettled boundary. Cross-border incursions of a broadly official kind were common throughout the Middle Ages; consequently, castles and fortified bastle houses dot the district. Later this was the Border Reivers’ country; marauding bands of cattle rustlers, professional kidnappers and generally lawless brigands dominated both sides of the border from the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries with their destructive raids, called ridings, and their fast-shifting alliances and treacheries.

Onto this fierce, and fiercely beautiful, territory in the early 1920s the newly formed Forestry Commission imposed the largest artificial woodland in Europe: Kielder Forest. There are 250 square miles of it; from Hadrian’s Wall it runs almost broken for 30 miles northwards, across the border and into Scotland,

2

and east to west it is more than twenty miles wide. Commercially, it is the Forestry Commission’s most successful ‘wood factory’ as well as its most extensive, and it produces nearly half a million cubic metres of felled timber a year: a major industrial site in the middle of nowhere. Roy Robinson, one of the first Forestry Commissioners, was so proud of it that when he was given his peerage in 1947 he chose the title of Baron Robinson of Kielder Forest and Adelaide. (He was an Australian and the only one of the seven original Commissioners who was not from the standard ‘country estate, public school, Oxbridge’ background.)

And this is why, through a darkening wintery afternoon, we were driving over Carter’s Bar and down into Northumberland. We were going to visit Kielder Forest to try and understand more about the Forestry Commission and its relationship with ancient woodlands. It is impossible to think seriously about woodland in the UK without looking at the role of the Forestry Commission over the last century, though quite what that role is feels hard to determine. If woodland itself is the heroine of this fairy story, is the Forestry Commission her wicked stepmother, her wise king, her rescuing prince, a dark witch or a wise animal? Until the last few years the Commission has been the principal villain of most conservation and preservation discourse. It stands accused of planting excessively on its own land, suitable or unsuitable – in retrospect, it is hard to tell whether the planting within old woodland or the attempt to create forests in places quite unsuited to any trees at all did the most environmental damage. At the same time the Commission is also accused of encouraging private landowners to join in and of squeezing extravagant tax concessions for the rich out of successive governments. In this version of the fairytale, the Forestry Commission was said to be economically deceitful and incompetent; to have wantonly destroyed old woodland; to have restricted access to wide reaches of the countryside; to have totally failed to live up to any of its original remit; and, both through its own actions and by subsidising private landowners, to have desecrated the wild places of Britain (and particularly Scotland) with square-edged unnatural-looking clumps of forestry which litter the hills and look more industrial than natural.

3

Although actually many of these accusations, especially perhaps the last, are hideously true, more recently the frog has been turning into a prince. The Commission has undergone a transformation – visible in the policy changes it has made since the 1990s.

4

I think there are, and indeed should be, serious questions to be asked about any organisation which owns, manages or controls over 12% of the land surface of a country, which is publicly funded but unaccountable and unelected (the Crown still appoints the Commissioners), and which is both the regulatory authority over and a business rival to all other commercial forests. Nonetheless, and especially since the 1990s, the situation is more complicated than this.

A good deal of the complexity is a direct consequence of the history of the Forestry Commission itself, which, like royal afforestation in the eleventh and twelfth centuries and enclosures in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, has profoundly changed the nature and meaning of our forests.

The Forestry Commission was established by legislation in 1919. During the 1914-18 war there had been a fearful realisation that there were insufficient timber reserves in the country and that this was partly because of the neglect of forestry in the previous century and partly because of a lack of strategic planning. In 1914 less than 4% of the timber used in Britain was home grown; about half was imported from Russia, and the rest from the Baltic, Scandinavia and Canada. This supply was critically threatened by German attacks on merchant shipping. At the same time, the construction and shoring up of trenches, as well as the building of barracks, encampments, transport infrastructure and so on, massively increased the need for timber: it has been calculated that

each

soldier deployed on the Western Front used up five trees. This crisis inspired the then government to set up the Commission with overall responsibility both for direct forestry development work on its own estates and for advising and regulating privately owned woodland. Although it was created to secure the nation’s supply of this crucial commodity, it was argued simultaneously that there was a handsome profit to be made out of well-managed forestry.

5

The new Commission needed to acquire plantations and was therefore given a budget to purchase appropriate ground; to prime that pump it was handed control over all the woodlands of the Crown Estate, including the remaining Royal Forests,

6

and, therefore, as I have explained, a large part of the remaining ancient woodland across Britain. This created a second, internal conflict of interests: the Commission’s primary duty was to increase timber yield and do so at a profit; this was inevitably in conflict with conservation. In its early years the Commission was keen not just on planting commercially within ancient woodland (not usually a very successful strategy, and one which tended to destroy old woods without generating useable or sustainable new timber), but also on clear-felling old woodland and grubbing it out to create new plantations.

The Forestry Commission did not invent plantations. The earliest recorded deliberate planting of trees other than orchards or in gardens in Europe is from the first century AD. In his massive Latin work

De Re Rustica

, the author, Columella, discusses planting chestnut or oak coppices alongside vineyards, to provide stakes for the vines.

7

His text appears to treat the idea of creating deliberate and extensive plantations as a part of normal agricultural activity, so it was probably already a regular practice. It certainly continued to be so: Oliver Rackham records seven references to plantations in Britain before 1500 (there were presumably more), and other European countries show a similar development. For example, there are records of plantation forests in south-western France as early as 1500, primarily for commercial purposes, but also to meet direct domestic needs. There were managed plantations of cork in Portugal and poplar in Italy.

8

By the seventeenth century several writers, particularly in Britain and France, were beginning to advocate plantations to landowners for their ‘pleasure and profit’.

9

Sadly, these two aspirations have not proved reliably compatible and the tension between them has bedevilled British forestry ever since.

Through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, planting, both within old woods and on new (usually ex-agricultural and common) land, continued steadily. Plantations, in terms of area, overtook ancient woodland surprisingly early – by about 1720 in Ireland, 1800 in Scotland,

10

1820 in Wales, and 1870 in England (with the exception of Essex, where it has not happened yet). So initially the Forestry Commission appeared simply to offer economy of scale and leadership. But the Commission has never quite worked as planned, or achieved the goals it set itself. And these goals have kept changing. Over the course of what is now almost a whole century, the Commission has had six successive and incompatible priorities, without ever officially abandoning any of its previous core objectives; these have been, in chronological order: assuring a national timber reserve; halting rural population decline; saving imports; creating jobs (specifically for the unemployed during the Depression); making money; and, most recently, protecting wildlife habitats and providing public amenity space.

We do not yet know about the last of these, but all the others have proved, in one way or another, illusory. Forestry has not provided jobs to the extent that was anticipated – mainly because of technological advances; we no longer need a strategic timber reserve because there is no more call for pit props, military trench supports or railway sleepers – even the use of matches has declined sharply, and in any case, the sort of timber we can grow commercially is never going to free the country from the need to import; and plantation forestry does not in fact make much money either for the nation through the Commission or for private owners – except via tax incentives. This financial aim proved perhaps the most destructive: in the years after the Second World War the Forestry Commission became almost grandiosely ambitious. Forestry gobbled up land between 1950 and 1980 to the extent that this period has become known as ‘the Locust Years’. At its peak in the 1970s, new planting in Wales, Scotland and northern England was consuming more than 0.15% of the total land area per year. Over half a million acres (240,000 hectares) of what is now Highlands and Islands was planted; 20% of Dumfries and Galloway was put under forestry. Overall, 17% of Scotland is now forested, and the vast bulk of that is non-native conifer plantation divided fairly evenly between the Forestry Commission and private ownership. Some of this was so far north, or on such unpromisingly peaty ground, that it inflicted great environmental loss without even offering any true potential for profit. It looked horribly ugly to many people – a neighbour of mine, a tenant hill farmer, when consulted about a proposed wind farm on the high moor here, said that they could do what they liked – it could not possibly be worse than the forestry. When he was a boy the moors were completely treeless, but the plantations had so changed the views and the ecology of the area that wind farms seemed unimportant to him, except that, once constructed, they would not get in the way of the sheep, as the trees do.