Full Tilt (24 page)

Authors: Dervla Murphy

The things they can do here with pine-trunks and stones are incredible. All the way from Chilas the many bridges over the nullah are constructed of these materials only; I went under one to see how it’s done but I’m not mechanically-minded enough to describe the technique. Of course this means that they cost nothing but labour, which is just as well, since they are swept away regularly every year.

Timber is one of the chief sources of cash here; it’s cut high on the mountains, rolled down to the track, carried by men to the Indus, thrown in and fished out hundreds of miles downstream years later, by the contractors who have bought the trees and whose name is carved on them. The locals have a curious method of felling; they burn the trunk near the ground until it’s thin enough to cut through with their tiny home-made axes. Great skill is required not to (

a

) set the whole tree on fire or (

b

) set the whole dry forest on fire. When the trees have been felled it’s fascinating to see small boys steering the giant trunks down steep slopes to the track.

For a combination of beauty, danger, excitement and hardship (of the enjoyable variety) today wins at a canter.

As I was resolutely chewing my breakfast of beans and one

chapatti

(made from about two ounces of maize flour and given me in honour of the occasion) an incoherent but kindly old man came along and told me that a pony-caravan had left the hamlet about three hours ago in a desperate attempt to cross the pass on the Mahomet-Mountain principle; they hope to collect essential stores from the camel-caravan which has now been held up at Butikundi for ten days. At the time I didn’t quite grasp why the old man was telling me this – but before long I got the message!

Roz and I started out at 7 a.m. (it was rather a holiday feeling not having to be up at 4 a.m. to beat the sun) and it took me nearly two and a half hours to walk slowly up the six miles I came down yesterday in less than one and a half hours. On this stretch I passed several groups of nomads, the smoke from their little camp-fires sending an incongruously cosy smell across the bleak landscape. Equally

incongruous

seemed the persistent call of a cuckoo. Apart from this, the only sounds to break the distinctive silence of high places were the whistles of nomads directing their flocks and the careless melody of sheep and goat bells.

I reached the first glacier in good shape, but the sun was now high and I noted with some alarm that this great bank of melting snow had moved a few yards since yesterday. However, the pony-trail was encouragingly clear and we were soon safely over; it was at this point

that the penny dropped and I saw the import of the old man’s

information

. I stopped here to eat some of the glacier, remembering my last meal of snow in the mountains between Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. Already I was almost painfully hungry and apart from quenching my thirst the feel of the solid snow in my mouth was absurdly welcome.

For another mile the track remained clear, though so torn by the thaw that it resembled a river-bed. At this height no trees grow and the rock-strewn pastures, which in a few weeks will be a rich green, were wearily yellow after the long winter. Ahead I could now see a gigantic glacier, more than two miles wide, extending to the Top. The track disappeared beneath this about a mile to the west of where it crossed the Top and hoof-prints in the thaw-soft earth showed me that the ponies had branched off to take a direct route up, cutting all the hairpin bends which obviously lay beneath the glacier.

At this point I stopped to consider what I should do. To follow the track approximately would be much less exhausting than to take the short-cut, but it might be much more dangerous for someone ignorant of the idiosyncrasies of glaciers. So I decided to drag Roz up the direct route, not suspecting that what looked like a twenty-minute climb would take almost two hours.

By now clouds were dark and close, and a sharp wind sent gusts of little snowflakes whirling around me at intervals. I revelled in this and went bare-headed, enjoying the keenness of the air. High peaks surrounded me, cutting off the valley below, and it was a rare joy to move alone among them with the chaotic symphony of re-echoing thunder as background music.

I was now higher than I had ever been before and when I stopped at six-minute intervals to regain breath my heart-beats sounded as loud as the thunder. This suffocating sensation frightened me until I realised that the illusory feeling of repeatedly coming to the point of death was simply the mountains’ way of teasing novices. By the time I was halfway up the ponies’ wisdom seemed open to doubt – their trail crossed many outcrops of rock and every time I lifted Roz over one of these barriers I collapsed with exhaustion. In places the snow was so soft that I sank into it up to the knees. Elsewhere it was so hard that

even the ponies’ hoofs had made little impression and I kept upright only by driving my specially nailed boots into it at each step – a process which still further exhausted me. After about an hour and a half of this struggle I was at that peculiar stage when one doesn’t really believe that one’s objective will ever be reached, and when one’s only mental awareness concerns the joy (to some incomprehensible, if not downright unnatural) of driving one’s body far beyond the limits of its natural endurance. Then, having dragged Roz up another savage gradient, and over yet another litter of boulders, we suddenly found ourselves on a level plateau, about a quarter of a mile square. Sitting where I had subsided beyond the rocks, and still clutching Roz, I slowly assimilated the unlikely fact that we were on Babusar Top.

I was understandably anxious to photograph Roz at this historic point where, because of her owner’s mental unsoundness, she had become the first bicycle to cross the Babusar Pass; but though I took three shots I doubt if the light was strong enough for a cheap camera. Yet, between the intermittent snowfalls, I had a clear view to east and south, where the sun was bright on a sparkle of angular peaks and on the flawless, smooth curves of the glaciers that united them.

By now the thunder had ceased and when the wind dropped the overwhelming silence of the mountains reminded me of the hush felt in a great empty Gothic cathedral at dusk – a silence which is beautiful in itself. However, I could afford no more than half an hour on the Top, for I was still fifteen miles from the head of the Kagan Valley. In my enthusiasm to get

up

, the process of getting

down

again had not been very seriously considered; possibly I was suffering from lack of vitamins to the brain, because I’d assumed that once on the south side all hazards would be left behind. This delusion was fostered during the first stage of the descent.

From the plateau I could see, about 1,000 feet below me, a vividly green valley some eight miles long and two miles wide, with a

foam-white

nullah flashing down its centre, and a reasonably-surfaced earth track descending at a comfortable gradient along the flank of the mountain, where snow had lain too recently for any growth to have covered the brown scree. On reaching the valley floor the track crossed

the nullah and was visible running level along the base of the opposite mountains before curving away out of sight halfway down the valley. As we began to free-wheel I reflected that this was a delightful road to follow, with all the characteristics which thrill a wanderer’s heart.

Half an hour later I was rapidly revising my opinion. The track’s first imperfection was revealed when we arrived at the nullah, to find that where a bridge should be stood two supports, stoutly upholding nothing. I looked up and down stream with wild surmise. The ponies had not returned, therefore the ponies had forded the nullah at some point. But at what point? Unfortunately the ground here was so firm, and the bank so stony, that my diligent search for prints yielded no clues. Then, as I stood looking pathetically around me, in the faint hope of seeing some nomads, a solitary black cow (for all the world like a good little Kerry) appeared some twenty yards upstream, walking purposefully across the meadow towards the torrent. There was no other sign of life in the valley, either human or animal, and in

retrospect

I tend to believe that she was my guardian angel, discreetly disguised. But when I first noticed her I did not pause to speculate on her nature or origin. She was obviously going to ford the nullah for some good reason of her own, and we were going with her. I pedalled rapidly and bumpily over the grass to the point for which she was heading. There I hastily unstrapped the saddlebag, tied it to my head with a length of rope mentally and appropriately labelled ‘

FOR

EMERGENCIES

’, and was ready to enter the water.

The cow, when she joined us on the bank, showed no surprise at our presence, nor did she register any alarm or despondency as I put my right arm round her neck, gripped Roz’s crossbar firmly with my left hand, and accompanied her into the turmoil of icy water. It had occurred to me that if I found myself out of my depth this could become an Awkward Situation, but actually the water was never more than four feet deep, though its tremendous force would have unbalanced me had I been alone. My friend, however, was clearly used to this rôle and we crossed without difficulty, unless the agony of being two-thirds submerged in newly melted snow counts as a difficulty. I felt that there was a certain lack of civility about our

abrupt parting on the opposite bank, after such a meaningful though brief association, but our ways lay in different directions and I could do nothing to express my gratitude. So I can only record here my thanks for the fairytale appearance of this little black cow.

I was now almost paralysed by the cold – soaked clothes are one thing in the desert and another thing here. After replacing the saddlebag, I couldn’t tie it on, my fingers were so numb, so I had to rope it instead, before cycling over the smooth turf to the road about half a mile away. From here the track climbed steeply (which I considered frightfully bad form; having gone up

all

the way

to

the Top it should now have had the decency to go down

all

the way

from

the Top) and this was the drill for the next seven miles, switch-backing up and down or round the flanks of mountains – all snow-peaked and overlooking wonderfully green pastures with more and more of those quite indescribable flowers. The pink and yellow and red and blue and purple and gold and white blooms often grew so thickly that the meadows looked like some giant’s carpet, with vast circular patterns of colour woven into the green background. (Isn’t it odd how the finest flowers grow where there are fewest people to see them?)

But I had other, less aesthetic distractions on this seven-mile stretch, during which I had to cross eleven glaciers, the majority forty to fifty yards wide. Eight were ‘natural’, i.e. situated where they had formed in gullies over streams, and the others were from high up the

mountainsides

and had slid down recently to their present positions. These were the ones which scared me, as I morbidly reckoned that there was nothing to stop them sliding still farther while Roz and I were in midstream, as you might say.

As before I followed in the steps of my thrice-blessed ponies (Allah be good to them!) but edging oneself and one’s cycle across steep masses of snow and ice, where one slip would be fatal, is a slow process, and it was 4.30 by the time I’d crossed those few miles. The last two miles curved round a most beautiful lake about half a mile wide with sheer green mountains rising from the opposite side, their gullies a-glitter with glaciers. The water was a clear but dark green and one of the loveliest sights of my life was the perfect reflection of

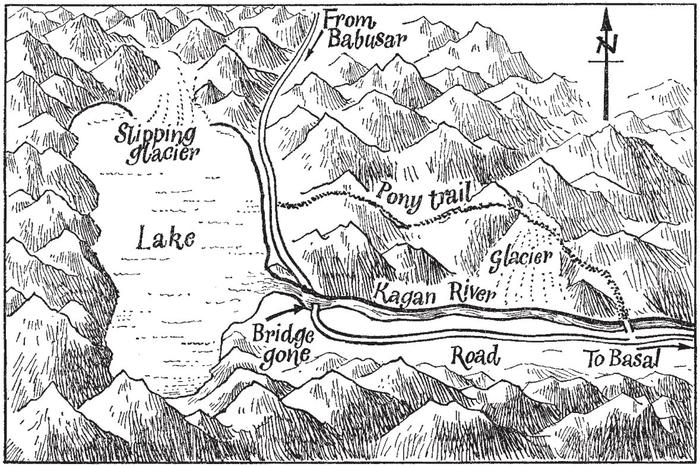

the white snow in that still depth of greenness. On my side of the slope, between road and water, was a natural rockery formed of small chunks of grey stone between which grew masses of blue and white flowers. At various points not far from the water’s edge were ‘icebergs’ – the tops of glaciers which had slid into the lake and not yet melted. The lake is shaped as shown below, and flows away in a nullah (the infant Kagan River, of which much more later); and as I cycled towards the nullah’s source I heard an odd, roaring noise in the distance. Before I’d time to diagnose it a movement caught my eye and I just saw a glacier disappearing into the water where the arrow points in my sketch. Wavelets began to lap the shore near me only minutes after, but the splash of the impact was most dramatic; it must have been a comparatively small glacier as none of it was left above the surface.

A few minutes later I came to the nullah and dismounted in disorder, confronted by the day’s Chief Crisis. The bridge, which should have been where I marked it, was gone, and this time there was no question of fording as the water was some twenty feet below the road between

sheer cliffs. (Here I began to feel that the day had contained enough thrills and that this was one too many.) I looked around in

bewilderment

, because of ponies there was no sign, yet it seemed inconceivable that they could have got through this impasse, as the road (see sketch) was overhung by a steep mountain strewn with great rough chunks of black rock. After a moment’s gazing at this I suddenly, and reluctantly, registered the horrible fact that since the ponies were not visible they must have gone

over

this mountain, however far-fetched the deduction might seem. And then I still more reluctantly registered the even more horrible fact that I too must go over this mountain, and quickly too, for at 4.30 p.m. only three hours of daylight remain. (Also I knew that I would soon collapse from starvation.) So the next thing was to rediscover the ponies’ trail.

To my surprise, this presented no difficulty (by now I expected everything to be difficult!) but to find it was one thing and to follow it was another. After the first few yards of carrying Roz up that gradient between those rocks my shins had been so badly banged about that I could have wept with pain, and Roz’s back mudguard, severely injured while crossing the earlier nullah, was now completely torn off. Clearly this nonsense had to stop, for both our sakes, and the only alternative was to wear Roz round my neck. Thus arrayed, I proceeded upwards, still suffering from lack of oxygen, with my head sticking out of the angle between crossbar and chain and my vision obscured by the front wheel. Being in a weakened condition the ludicrous aspect of the situation struck me with special force and whenever I stopped to rest I wasted precious breath on giggling feebly at my own dottiness.