Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (54 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

8.5Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Growing: Uterus, breasts and adipose tissue around the body

Often enjoy this phase: "blooming"

Acknowleging the pregnancy or not, sometimes women deny and do not plan untilthey are confident about viability of the fetus

More connection with the baby, nurturing may become evident and protective instincts may emerge

Becoming real for partner

(b)

Carpaltunnel syndrome

Varicose veins

Tiredness returns

Frequency of micturition/vaginal discharge

Back ache/pelvic girdlediscomfort/pain

Connection with the baby stronger, may talk to and dream of baby and protective instincts may emerge

Planning for the birth and parenting, attending birth preparation classes

Partners and others may become nurturing or anxious

Possible maternity leave if working

Shopping and preparing for caring for baby

Figure 6.1

(a) First trimester of pregnancy: a hidden but dramatic influence; (b) second trimester of pregnancy: body shape changing; (c) third tr

i

mester of pregnancy: now obviously pregnant.

Source

:

Reproduced with permission from

J.

Green.

chemical cascade that prepares the body for fight or fright, or equally when the response is resulting fromasexualinteraction. If arousal(whichcanbefear) continuesandthehypothalamic– pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis is stimulated for a sustained length of time, cortisol is secreted. Although this has clear implications for acutely affecting the optimal hormonal balance, low level secretion also needs to be considered, particularly as Jomeen and Martin (2005) highlight that women can be at risk of anxiety in pregnancy anyway.

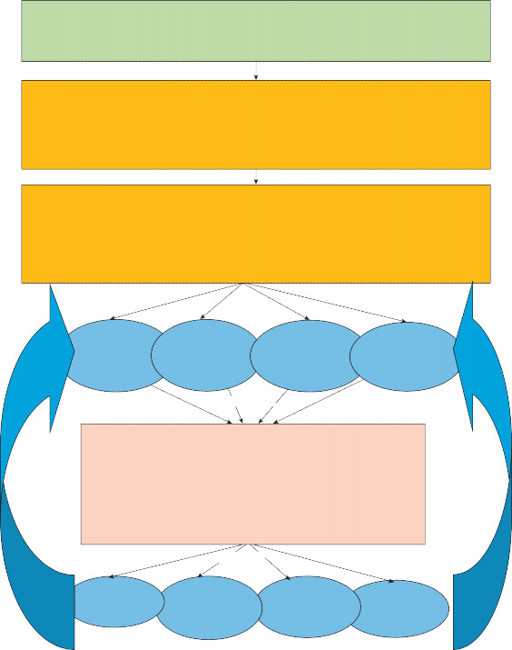

Having looked at the influences of policy and pregnancy screening on maternal choices throughout antenatal care, women’s ability to make choices should be considered, particularly about their intentions for coping with the discomforts of pregnancy, labour and birth and how this can be influenced by the culture of birth around them. Women often share their experiences of pregnancy and birth; these stories contribute to influencing the culture, knowledge and confidence in the birthing process of subsequent childbearing women. Therefore, potentially if more women share good experiences they may generate more confidence and potentially less intervention in the women who follow them into the childbirth journey. This, in turn, re-informs women, service providers, the wider community and general culture of birth. Figure 6.2 high- lights the influences on a woman’s decision making.

As previously stated, initiatives have called for service providers to promote choice and empowered decision-making (DH 2007). It has long been apparent that an effective interface between users and service providers is crucial to ensure women are confident and prepared for their birth experience (Green et al. 2003). Increased use of birth technologies and interventions over recent years has alarmed experts and women (Johanson et al. 2002).

Women’s self-identity and decision-making about care

Women are consumers in maternity services and therefore active decision-makers about their

care and as such should be valued. Their self-identity influences how they will interact with health professionals and their self-perception throughout childbirth. Pregnant women are exposed to new situations and dilemmas and may feel potentially vulnerable as they navigate choices about care (Edwards 2005). For some women, this vulnerability in making decisions about themselves and their unborn babies may be overwhelming (Santalahti et al. 1998). Van de Vusse (1999) demonstrated that more positive birth experiences occur when women are involved in decision-making and more negative experiences are experienced when they are not. Even though women are encouraged to take part in decision-making, some might be actively involved (Harrison et al. 2003) and some may refrain, assuming a passive role (Moffat et al. 2007). This does not mean they are any less satisfied with the decisions made (Blix- Lindstrom et al. 2004), but as women experience increased feelings of responsibility for their own and their babies’ health, they differ in the level of involvement they want to have in the decision-making process. Therefore, some women seem satisfied with passive involvement; women with pregnancy complications seem to have less opportunity for involvement in decision-making and are often content to rely on the expertise of the practitioner. For some women it might be enough that they are consulted about decisions even if they do not want to take an active role in decisions about their care. This does not mean they are excluded from, or not offered opportunities to participate in decisions regarding their bodies. Midwives should remain mindful of different women’s situations, so opportunities for women to remain active in decision-making about their care are offered throughout the childbearing journey. The most

131

National policy on care provision

Choice for place of birth and direct access to midwife or GP referral into maternity service provision

132

Individual woman first pregnant, making decisions

Midwife undertakes booking for care and screening

Determining risks (midwifery led-care/consultant led-care) – Woman’s view of wellness, self identity and risk, some choices are already made.

Individual woman throughout pregnancy, making decisions

The woman's knowledge and emotional state are influenced by relationships and inherent culture, as well as the ongoing risk assessment, underpinning her subsequent choices and decision making.

However, health professionals need to consider the quality of information and experience within each of these:

Influencing

Woman’s

self/experience Midwife/Doctor Culture/Media

Supporters/ Peers

Influencing

Choice of birth place and any possible intrapartum interventions (see Chapter 7)

The outcomes and experiences inform the elements below; this feeds back into the views of all the individuals above influencing beliefs about birth.

Influencing

Physical

Psychological & Emotional

Spiritual and Social

Cultural change

Figure 6.2

Factors influencing maternal choices in pregnancy.

important factor seems to be the ability of the professional to support them in their preferred role in the decision-making process (Harrison et al. 2003).

Midwife–woman relationship for decision-making

Midwives and women have a relationship that is fundamental to midwifery and one that is

the foundation to midwifery care (Kirkham 2010). Hunter et al. (2008) describes maternity care as a tapestry; weft threads represent clinical outcomes, policies, protocols and technologies and the interwoven warp threads represent the relationships between midwives and woman that hold it all together. Women trust and use the expertise of health professionals and feel more satisfied if care from them is harmonious with what they want (Harrison et al. 2003). For some time now that trust has been recognised; Tinkler and Quinney (1998) demonstrated that trust is just one factor that affects satisfaction. They consider how the midwife–woman rela- tionship influences experiences and perceptions of care, and re-affirm the midwife–women relationship as an important aspect of satisfaction. Others who have written on this subject found that women implicitly trust the midwives who care for them and even when their own wishes were disregarded, trust is maintained (Bluff and Holloway 1994). Such implicit trust must be handled professionally in open dialogue so that midwives do not simply dictate what will happen.

Influencing women in their decision-making

There is limited literature that illuminates understanding about what truly influences women’s

decision-making for birth. Barber and Rogers (2006) illustrated how midwives have great influ- ence over women with regard to choice of birth places and they found that women are often left with limited information on which to base their choice options on. The influence midwives have on women is also highlighted by Levy (1999), who was first to research how midwives facilitate the process of informed choice to women in pregnancy and aimed to identify the processes midwives engage in for assisting women to make informed choices. Levy identified ways midwives communicated with women about their choices, steering them towards a safer course of care, which she termed ‘protective gate keeping’. Midwives would both provide infor- mation to women, but also guard it and release it at the time to suit the midwife. Levy high- lighted how midwives ‘walked a tightrope’ when facilitating informed choice in an attempt to meet the wishes of women. Midwives would steer themselves through a number of dilemmas, anxious to meet the desires of women and appear impartial in their advice, while acknowledg- ing their own sentiments about certain issues (Levy 1999).

So the implication of this influence on women’s decision-making is that women might simply comply with the professionals who care for them. Women’s decisions are guided by the profes- sionals because women see them as experts. Women accept suggestions because they feel listened to, but this means women comply with midwives, rather than actually choosing how they want to give birth (Kirkham 2010; Van de Vusse 1999; Freeman et al. 2006). These notions of professional gate keeping and influential practitioner beliefs could lead to manipulation of women in the decision-making process, where women comply with professional judgement because they do not want to be seen in a bad light.

Other books

Lady Ellingham and the Theft of the Stansfield Necklace: A Regency Romance by Rochester, Miriam

Taking Pity by David Mark

The Complete Yes Minister by Eddington, Paul Hawthorne Nigel

The Heart Of It by M. O'Keefe

All We Know Is Falling: Fall With Me: Volume One by Nicole Thorn

The Indian Tycoon's Marriage Deal by Adite Banerjie

Justified Treason (Endless Horizon Pirate Stories, Book 1) by Taijeron, Cristi

The Rest of Us: A Novel by Lott, Jessica

Fake by D. Breeze

The Lone Pilgrim by Laurie Colwin