Fusiliers (10 page)

Why Lieutenant John Lenthall Bid Adieu to the 23rd

Service on the lines offered few prospects for distinction. Instead there were hours of tedium and a small but distinct chance of ruin.

Just after midnight, in the early hours of 27 July, Lieutenant John Lenthall of the 23rd was nearing the end of his duty and looking forward to being relieved. He and a couple of dozen Fusiliers were manning the outposts just ahead of British lines on Charlestown Neck. The guard’s job was to provide early warning of any attack and prevent rebels approaching the newly dug trenches to their rear. This particular evening was a warm summer’s one, but particularly dark. Taking advantage of the poor visibility, a party of Virginia riflemen crept towards the British posts.

The first Lenthall knew of the danger was when the night calm was shattered by an explosion of musketry. One of his sentries had opened fire on the infiltrators. Shouting above the noise, he rallied his men into formation and ordered a volley towards a group of riflemen. It quickly became apparent that enemy parties were moving about him in large numbers, the lieutenant writing, ‘the rascals called out to us several times to surrender’.

Fortunately for the Fusiliers, their relief appeared at this moment out of the darkness. Hastening towards the sound of shooting, the second subaltern’s party began to fire in support of Lenthall’s men. Both British and American troops took their chance to break off the night action, falling back to their respective lines. ‘Their intention was to have taken all of us prisoners,’ the Fusilier lieutenant wrote, adding it was ‘a narrow escape’, since the American party had far outnumbered them.

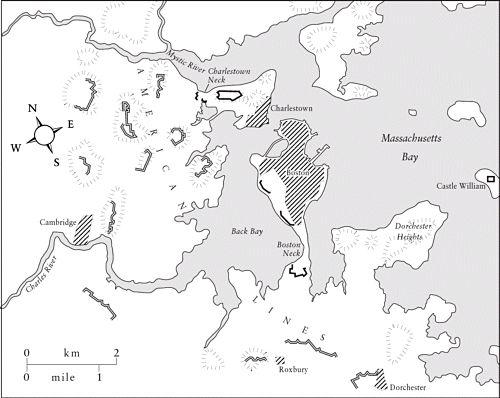

The Boston siege lines

Lenthall was the acting commander of the 23rd’s grenadier company. By late July he had already been in action at Lexington and Bunker Hill, where he was wounded. The twenty-five-year-old subaltern had quickly returned to his duty, unlike his captain who was still indisposed. Having been an eyewitness to the confusion of those two actions, Lenthall knew all about the defects in British discipline.

When the army launched a raid in retaliation for the night attack of 27 July, it turned into a fiasco. Lenthall was sent ahead of British lines at the head of a party with orders to move several hundred yards north to Penny Ferry, where the Mystic River narrowed to a crossing point, and then push up the riverside road, wreaking further vengeance. Their intention was to creep forward with the same stealth that the Americans had shown, burn down some houses used as guard posts and take prisoners. What happened is best described in the lieutenant’s own words:

We burnt Penny Ferry House … and should have taken the whole guard and

burnt the barns up Mystic road, had our men behaved like men and soldiers and obeyed orders, which were upon no account to fire even if fired upon. They fired and to mend the matter ran away without even having their fire returned.

Lenthall managed to collar a few of his panic-stricken soldiers to carry off a captain of marines. It was the least the Fusilier lieutenant could do, since it was his own fearful grenadiers who had shot the poor man. The raid ended without prisoners and cost the life of that British captain who later died of his wounds.

Lenthall’s affair was no isolated incident. Lieutenant Richard Williams could have brought his own example to the 23rd’s mess table. One month before, at the same spot on the lines, he had also been involved in a chaotic action. When a patrol had been sent out from one of the two bastions on the Charlestown Neck defences, men in the other strong-point had not known anything about it and ‘gave a general fire of small arms on them’. The two British companies had blazed away at one another until calm had been restored. Williams blamed, in part, the officer leading the patrol, for he had not informed those along the line what he planned to do.

However, Williams, like Lenthall, reserved his toughest invective for the soldiers, criticising ‘the hurry and inattention natural to young troops … who never having seen service, foolishly imagine that when danger is feared they secure themselves by discharging their muskets with or without aim’. Williams believed that matters would get better as experience built: ‘Theory is nothing without practice, and it requires one campaign at least to make a good soldier.’

While much of the 23rd had not been present at Bunker Hill, it was clear then that its soldiers were guilty of the same indiscipline that Burgoyne, Rawdon or Howe had lamented at that battle. Invested by vast numbers of rebels, the garrison’s morale had slumped. The regiment was a shadow of its former self, its Minden self. What could be done to curb its men and make them worthy Fusiliers?

Most were agreed that some tough steps had to be taken to restore discipline. This was easier said – in some General Order put out by Headquarters – than it was done by the young officers who bore the brunt of actual duty. The lieutenant or captain who tried to grab some running soldier or prevent another from looting an American’s house could receive volleys of abuse in return. Williams or Lenthall suffered many handicaps in trying to get their men to do as ordered. An officer who allowed soldiers to insult him would risk losing all authority,

whereas one who wielded the rod too readily might meet with unpleasant reprisals.

Several days before the incident on the lines, Lenthall had brought a grenadier of the 4th to a general court martial. The man was charged with mutiny and insolence following an altercation with the lieutenant. Mutiny was a capital charge, but General Gage’s aversion to the death penalty would have been well known to the court and in the end it had found the grenadier guilty only of insolence. The outcome was duly announced in Orders, and the offender ‘sentenced to receive 500 lashes at such place and time as the Commander-in-chief shall think proper’. Even in this particular though, Gage left himself free to release the soldier without further punishment.

Not only was the outcome of charging a soldier uncertain, but there were also risks for the officer who attempted it. Boston had heard the rumours about poor Lieutenant Hull of the 43rd. After being wounded at Concord on 19 April, he had been captured and placed under guard of several deserters. One of these former redcoats swore revenge on Hull, who had previously brought him to a court martial. Hull had died in captivity. Whether the rumour was true or not, its currency showed officers’ awareness that a soldier who considered himself wronged might find opportunities for revenge.

During the Boston siege the rank and file might also have cursed the incompetence of those supposed to lead them. The raid on Penny Ferry was followed in August by a general plan to ‘alarm’ the enemy conceived by Major General Clinton. The main effort was launched at Boston Neck, where he led hundreds of troops on a mission to beat up the enemy camps around Roxbury.

Clinton recorded that ‘the detachment I was with succeeded to my utmost expectations’. The raiders soon found themselves in the middle of Roxbury, having caused the American militia to flee. Once there, Clinton did not know what to do. He later blamed Gage for ordering him back but some officers wondered why they had not at least burned Roxbury. The answer, farcically, was that those planning the enterprise ‘had forgot to bring any combustibles’.

Following these raids, the Americans embarked on a frenzied bout of pick and shovel work, throwing up redoubts and batteries so as to thwart the chance of more British sorties from the city. Although the execution of Clinton’s attack had been poor, the general’s reasoning was right in one particular at least; an active scheme of defence could

have helped maintain morale and denied the Americans various opportunities for mischief.

Instead, Gage allowed an acceptance that no further strategic initiatives would be possible in 1775 to blind him to the tactical requirements of holding Boston. The headland of Dorchester, for example, had been an object of British designs earlier in the summer but remained unoccupied. Their failure to secure this land was all the more puzzling given senior officers’ acknowledgement that an American appearance there would reproduce the crisis of 17 June and call into question their very presence in Boston. On the lines or waters surrounding the city, meanwhile, the enemy carried out raids, taking prisoners and prize ships alike.

For those not taking their turns on the defences, the city offered a depressing prospect. When they had arrived in Boston before the war, many of the British officers had been struck by the beauty of its setting. ‘The entrance to the harbour,’ wrote one, ‘and the view of the town of Boston from it, is the most charming thing I ever saw.’ The isthmus upon which the town was built was hilly, creating a pleasing panorama of rising and tumbling roofs.

After war broke out, the blockade changed everything. Streets that had previously thronged with townsfolk echoed only to the march of redcoat companies. As the days grew shorter, hundreds of houses stood unlit, their Whig inhabitants having fled. Food and other necessaries became extremely expensive because trade with the backcountry had been entirely severed. Ravenous soldiers awaited the arrival of each new vessel in the hope that it might bring something tasty to eat. Their dislike for Admiral Graves, already blamed for not throttling the rebel naval privateers, reached a new pitch when he was discovered to have kept a consignment of delicacies from the West Indies – turtles and pineapples, no less – to himself.

Most days officers and men alike chewed their way through vile salt pork or other preserved rations that caused all manner of fluxes and agues. Dozens of redcoats’ wives had been pressed into service as nurses, first to treat the huge number of casualties from Bunker Hill in makeshift hospitals and later to look after the growing number stricken by bad rations and disease.

Throughout the late summer and autumn of 1775, the soldiers watched a procession of civilians packing up their conveyances and quit the city. The blockade meant they had to share the army’s

unhealthy diet and one letter writer recorded in August that ‘every inhabitant that can get away is going’. The population dwindled from 17,000 before the war to as few as 5,000 civilians. Those who tried to sell their possessions found prices for luxurious furniture or fine horses tumbling.

Many soldiers might have envied the Bostonians who passed their sentry posts on the neck and headed into the lush New England hinterland. But the siege had made desertion far more difficult, notwithstanding generous offers that were being made to seduce redcoats.

Soon after Lexington, handbills had begun circulating promising the men land and a new life if they defected. ‘If you will quit the service, and join your American brethren,’ read one such paper, ‘you shall be kindly received as brothers and friends, and provided with a comfortable subsistence among us: you shall be sent with a proper escort to any part of the continent where you choose to retire, together with your wives, children and effects.’

It was hard though to sneak past the lines. Even taking the ferry to the Charlestown peninsula required a special permit, a measure designed to thwart would-be deserters. Only the ingenious could defeat these precautions, and on 27 July, Thomas Machin of the 23rd succeeded.

Machin, a soldier of Blunt’s company, was literate, intelligent and Irish – a troublesome combination in those times. He had been ordered to do duty with another soldier as lookouts on one of the boats anchored in the harbour as a precaution against enemy attack by water. Machin waited until his partner was asleep before paddling off in the canoe that they used to get to and from the guard boat. He had the foresight to take both muskets with him so that if the other man woke, he would be powerless to stop the desertion. An officer in the Fusiliers noted, ‘This fellow will give them good intelligence of our works.’

The Machin case, though, was one of only a handful in the months since the war had begun. Preventive measures by the army, as well as the nature of the siege, made it harder but there was also an important change in attitudes. Soldiers, in common with their officers, had smarted after the battlefield debacles. The private with his pot of grog, no less than the captain sipping wine, gave vent to deepening anger, damning the rebels’ eyes, cursing their mouths or describing in blood-curdling terms what they would do to any Yankee rascal they came up with.

‘The next campaign will be carried on with an inveteracy unparalleled in the histories of modern wars,’ Lord Rawdon predicted in a letter back to England. The young officer shuddered at the idea of war without mercy: ‘Both sides hold each other in such detestation that which ever party is victorious it will not, I fear, use its power with moderation.’

In these difficult days amusement centred around drinking, gaming and whoring. Younger officers, like Lieutenant Colonel Bernard’s son, formed an Ugly Club at the Bunch of Grapes, a tavern on King Street, one of Boston’s main thoroughfares. There they drank rum or madeira, and it was considered the height of poor form to fall behind in the consumption of tumblers of alcohol. Others favoured the British Coffee House.