Fusiliers (7 page)

The British soldiers who retired that night in Boston had no way of knowing how many Americans they had accounted for. They tried to console themselves that they had faced 5,000 enemy, perhaps more. Casualties among the many companies that had taken potshots against the King’s troops were slight, almost certainly fewer than a hundred men, between forty and forty-five of whom had been killed.

Among the colonists exchanging experiences of that day’s fateful

events there were vivid impressions of panicked redcoats, faces flushed as they ran for their lives; of an entire brigade of the King’s troops racing its way back to Boston as fast as its legs could carry it; and of those who faltered – through wounds or because they went off to steal – being left to the mercy of an enraged people.

William Gordon, minister of the Congregational Church in Roxbury, one of those divines who had done so much to inspire the spirit of righteous resistance in the colonists, wrote to an English friend of the day’s events. ‘The Brigade under Lord Percy marched out, [playing] by way of contempt, “Yankee Doodle”,’ noted Gordon. ‘They afterwards told that they had been made to dance to it.’

‘They pillaged almost every house they passed by, breaking and destroying doors, windows and glasses &c and carrying off clothing and other valuable effects,’ wrote the impassioned correspondent of the

Essex Gazette

. ‘It appeared to be their design to destroy and burn all before them; and nothing but our vigorous pursuit prevented their infernal purposes from being put into execution.’

British officers and men smarted from what had happened. The expedition was ‘as ill planned and as ill executed as it was possible to be’, according to one officer, while another felt the soldiers behaved with ‘great bravery but little order’, and another, more laconic, letter-writer called Lexington and Concord ‘the little fracas … between us and the Yankee scoundrels’. Some shuddered at the recollection of how the light infantry had broken ranks at Lexington, opened fire without orders and later been so fearful that their own officers had to check the soldiers’ headlong flight with levelled bayonets.

Farmers, blacksmiths and mechanics had managed by adopting an irregular form of warfare to give a costly lesson to the army. By adopting these lilliputian tactics they had brought down the redcoats’ Gulliver-sized reputation. After 19 April 1775, revolt was open and general throughout the Thirteen Colonies – Britain found itself confronting the spectre of a strange and unwelcome war on the other side of the world.

It took a matter of hours for the troops in Boston to realise how much their situation had changed on the day they marched back from Concord. The rebels had chased them to the edge of the city, and within days thousands were congregating in armed camps in Roxbury, Cambridge and other outlying settlements. General Gage ordered

troops manning positions in the Neck to stop communication with the countryside across that narrow isthmus. This rule was soon relaxed in favour of hundreds of families who, sympathising with the Whigs, piled up their wagons and fled the city. A lesser number of Tory Americans who still felt loyal to their King came in the other direction, from some scattered communities where they felt in danger.

In many places across America, officials on royal service fled, magazines or stores were seized and Committees of Public Security established. Ugly scenes were repeated across the continent where mobs calling themselves ‘Sons of Liberty’ converged on the homes of noted loyalists to barrack them, break their windows and, in some cases, tar and feather them for public ridicule.

Boston remained the only sizeable garrison south of Canada. Gage’s army of around 3,500 men able to do duty was soon besieged by several times that number of Americans. Initially some 20,000 answered the call to arms, but as the weeks wore on this figure dropped somewhat. In May, following a skilful

coup de main

, the colonists took Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain, one of America’s principal fortresses, and by doing so seized a train of heavy siege guns that could be used to hit Boston.

Rhetorical artillery was also pressed into service, that hard-hitting preacher Dr Warren finding himself commissioned as a Major General in the militia. Many who actually knew the business of a soldier, veterans of the French and Indian Wars, also flocked to the Patriot cause. Some of these New Englanders had been part of Wolfe’s legendary march on Quebec back in 1759, and there were sufficient men of this species among the company, regimental and brigade commanders to instil some sound judgement into the American camp.

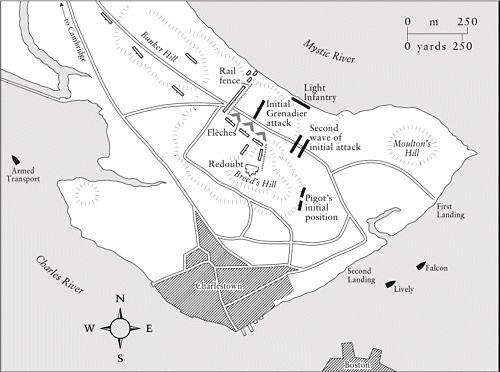

Initially, after the night of 19 April, British soldiers held positions across the water from the city at Charlestown. This was one of two places where headlands jutted into the bay sufficiently close to the city of Boston for artillery to pose a potential threat to British shipping at anchor. In the weeks following Lexington, British commanders gave much thought to conquering the heights both of Charlestown and Dorchester.

The British could not, however, decide quickly what they wanted to do about securing these two places and actually withdrew their forces from the heights above Charlestown. General Gage was nervous about a general rising within the city, an attempt to massacre his troops. He

did not want to post large detachments across the harbour in Charlestown or Dorchester, where there might be problems – for example during bad weather – ferrying them back, or indeed reinforcing them. Gage did not have enough troops to defend his situation. The chief engineer later decreed that Britain’s first big mistake of the war had been ‘taking post at Boston – a mere libel on common sense – being commanded all round’. Like many others, he would have preferred New York, a city abandoned after Lexington, but also in fact requiring the defence of a very large garrison.

Gage was required to re-think his position after 25 May, when the frigate

Cerberus

brought three British major generals to his assistance. All would prove significant in the struggle ahead. John Burgoyne was a cavalry officer, playwright and notorious gambler with excellent political connections. Henry Clinton, born in New York, had garnered much valuable experience in Germany during the Seven Years War. William Howe, having served in a key role in Wolfe’s attack on Quebec, was considered an authority on tactics to be used in America.

Hemmed in and outnumbered, the officers of Gage’s army entertained some disturbing reflections on what had happened at Lexington and Concord. Burgoyne, soon after arriving from England observed ‘men still lost in a sort of stupefaction which the events of the 19th of April had occasioned, and venting expressions of censure, anger, or despondency’. Some railed about the bad planning of that expedition. Others, like Mackenzie, also worried about the thieving and wild behaviour of many soldiers.

Lieutenant Barker, who had been with the 4th Regiment light company at Concord bridge, remarked: ‘Our soldiers the other day showed no want of courage, yet were so wild and irregular, that there was no keeping them in any order.’ As for their thieving, there was another issue at stake: ‘The plundering was shameful; many hardly thought of anything else; what was worse they were encouraged by some officers’. The problem of indiscipline, in other words, had been exacerbated by men in command who believed that the Americans deserved to be ‘scourged’ for taking the path of rebellion.

As the days following their first, unpleasant, experience of American warfare passed, the anger was directed away from internal recriminations and back towards the enemy, one lieutenant speaking for many when he wrote home early in June, ‘our troops I believe would be very glad to give them a good drubbing’.

By early June, a couple of weeks after the three new major generals had arrived, Gage had been persuaded to approve an offensive plan. The British army would take the heights of Dorchester and the Charlestown peninsula before moving on rebel headquarters at Cambridge. How, though, would they attack an enemy that skulked behind walls and fences?

Humphrey Bland was probably the most widely read of the many tactical theorists whose books informed British officers. He had summed up the army’s approach to war from the Duke of Marlborough’s great victories, seven decades before, to Minden and the Seven Years War. Bland distilled this experience to describe the formula for a perfect attack.

As you advanced your battalions in line, the enemy would be encouraged to waste their fire by opening up when their targets were still too far away. The redcoats would bide their time, answering with a single close-range volley, which would be followed instantly by a bayonet charge before their foe had a chance to re-load. Bland understood well the psychology of the defenders’ situation, noting that victory would often be won before the attacking line had reached the defences, for ‘when troops see others advance, and going to pour their fire amongst them, when theirs is gone, they will immediately give way’.

It was vital, in this description of the perfect assault, not to allow your troops to be stalled by the enemy and get into a running firefight, for in the thick smoke and frenzy of re-loading the attack would lose all momentum and fail, as the French had learned at Minden. Such episodes led Bland to give the following warning to any officer leading an assault: ‘If you do not follow your fire that moment, but give them time to recover from the disorder yours may have put them into, the scene may change to your disadvantage.’ These words could have been read as a portent of what was about to pass.

Benjamin Bernard would hear reports of the great drama that was unfolding in Boston from a sickbed. The ball that had shattered his leg on the 19 April had in fact finished his career as a soldier. Bernard, however, was not a man to relinquish command of the 23rd without a fight. He entertained hopes of convalescence and a return to duty, as the army prepared to confront the vast rebellion brewing in the country.

On 17 June 1775 the Boston garrison received a rude awakening. One of the Royal Navy ships in the harbour had opened up. The shot were directed at Breed’s Hill, an eminence on the Charlestown

peninsula where, overnight, thousands of rebel soldiers had seized the hill and by throwing up a system of trenches shown their intention of holding this ground. General Howe would claim in a letter home that they had pre-empted by a single day the launch of the British offensive. Howe, Gage and the others attending a hurried council of war ‘instantly determined’ to launch their plan, only to start at Charlestown rather than Dorchester. If the rebels were willing to stand there and defend themselves, then the British were ready to administer the bayonet, and give them a lesson in the realities of warfare.

FOUR

Captain Mecan’s Trial By Fire

There was a purposeful bustle on the Boston quay during the late morning of 17 June. Soldiers stepped gingerly from terra firma into the longboats arrayed in front of them. Encumbered with weapons, blanket, cartridges and knapsack, a fall into the water might easily have drowned them. Once aboard, the men of ten light and ten grenadier companies crowded knee to knee on the benches provided as tars from the fleet pushed off and rowed out towards Charlestown peninsula.

As regards the 23rd Fusiliers, the quarrelsome Captain Blakeney had on this day placed himself at the head of his grenadier company. Thomas Mecan joined the boats in command of the regiment’s light company. Although Captain Donkin was nominally responsible, he was absent, and Mecan, sensing a great day in which some feat of daring might bring the approbation of great men and with it a chance for promotion, had volunteered immediately to go in his stead. The main body of the 23rd, the eight so-called battalion companies, were not destined to see action that day.

The splashing of oars was accompanied that morning by the mad timpani of British guns. A battery of artillery in Boston itself was firing at the redoubt, some Royal Navy ships had joined in for good measure, and shallow-draught gun barges manoeuvred into place so that they could shoot at the Americans as they crossed the narrow neck connecting Charlestown peninsula to the mainland. It certainly occurred to some that cutting off the Americans by landing at this same narrow isthmus, behind their main position, might be the wisest plan of attack. But there were some navigational impediments – a dam

blocked passage to the neck’s southern flank and sand flats hindered (but did not completely prevent) landing to the north, on the shore of the Mystic River. Instead the generals at that morning’s council of war eschewed lengthy manoeuvres by boat that might have given their enemy time to escape and opted to land on the head of the peninsula.

The battle of Bunker Hill