Galileo's Daughter (14 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

Galileo fell ill again in early 1621. He recovered by midyear and completed most of

The Assayer

by year’s end. He composed the long polemic in the form of a letter to his friend and fellow Lyncean in Rome, Virginio Cesarini, Prince Cesi’s young cousin, who had been smitten by science under Galileo’s influence and written to him during the comet season to offer details of his own cometary observations.

“I have never understood, Your Excellency,” Galileo addressed Cesarini plaintively in the opening pages of

The Assayer,

“why it is that every one of the studies I have published in order to please or to serve other people has aroused in some men a certain perverse urge to detract, steal, or deprecate that modicum of merit which I thought I had earned, if not for my work, at least for its intention.”

In October 1622, Galileo delivered the long-awaited polished manuscript to Cesarini, who fine-tuned it further in collaboration with Prince Cesi before publication. As the printing neared completion the following summer, however, a puff of white smoke from the Sistine Chapel called the process to a halt.

Pope Gregory was dead. Galileo’s longtime acquaintance and admirer, Maffeo Cardinal Barberini, now succeeded him as Pope Urban VIII.

Quickly, Prince Cesi created a new engraved title page incorporating the three bees of the Barberini coat of arms. Though Galileo had addressed

The Assayer

to Virginio Cesarini, the Lynceans seized the political expedient of dedicating the book to the new pontiff. They offered up

The Assayer,

which had grown out of a spiteful argument over a trio of comets, as their literary entree into the papal court of Urban VIII.

On

Bellosguardo

How our

father is

favored

MOST ILLUSTRIOUS LORD FATHER

The happiness I derived from the gift of the letters you sent me, Sire, written to you by that most distinguished Cardinal, now elevated to the exalted position of Supreme Pontiff, was ineffable, for his letters so clearly express the affection this great man has for you, and also show how highly he values your abilities. I have read and reread them, savoring them in private, and I return them to you, as you insist, without having shown them to anyone else except Suor Arcangela, who has joined me in drawing the utmost joy from seeing how much our father is favored by persons of such caliber. May it please the Lord to grant you the robust health you will need to fulfill your desire to visit His Holiness, so that you can be even more greatly esteemed by him; and, seeing how many promises he makes you in his letters, we can entertain the hope that the Pope will readily grant you some sort of assistance for our brother.

In the meantime, we shall not fail to pray the Lord, from whom all grace descends, to bless you by letting you achieve all that you desire, so long as that be for the best.

I can only imagine, Sire, what a magnificent letter you must have written to His Holiness, to congratulate him on the occasion of his reaching this exalted rank, and, because I am more than a little bit curious, I yearn to see a copy of that letter, if it would please you to show it, and I thank you so much for the ones you have already sent, as well as for the melons which we enjoyed most gratefully. I have dashed off this note in considerable haste,

so

I beg your pardon if I have for that reason been sloppy or spoken amiss. I send you loving greetings along with the others here who always ask to be remembered to you.

FROM SAN MATTEO, THE 10TH DAY OF AUGUST.

Most affectionate daughter,

S.M.C.

Only four days previously, on August 6,1623, Maffeo Cardinal Barberini stood sweating in the Sistine Chapel, where he and more than fifty fellow cardinals had been locked together since mid-July in papal election proceedings. Absent the unified conviction, inspired by the Holy Spirit, that had led to the

acclamatio

selection of Gregory XV two years before, the Sacred College of Cardinals now prayed for guidance in the balloting. The members voted twice a day, morning and afternoon, each one prohibited from endorsing himself, and all of them disguising their handwriting to maintain the secrecy of the selection process. Every time the tabulation failed to produce the required two-thirds majority, the cardinal scrutineers bound the slips of paper and burned them in a special stove with wet straw, which sent up the black smoke of indecision. The typical heat and malaria that visited Rome every summer claimed the lives of six elderly cardinals in the conclave before the assembly at last cast fifty of its fifty-five ballots for Barberini as the new leader of the Church.

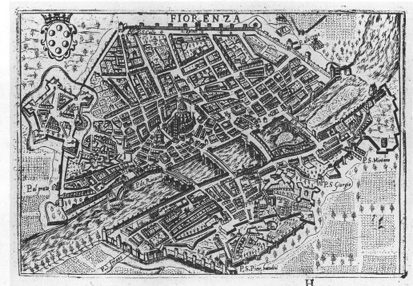

Florence in the late sixteenth century

“Do you, Most Reverend Lord Cardinal,” the chamberlain asked him face to face, “accept your election as Supreme Pontiff, which has been canonically carried out?”

“Accepto,”

he answered with the only word required.

“By what name will you be known?” The choices included his own Christian name, Maffeo, or the name of any pope who had preceded him—except Peter, of course, which tradition forbade.

At a stroke, Maffeo Barberini metamorphosed into Pope Urban VIII. The ballots, burned with dry straw instead of wet this time, announced their white smoke signal to the crowds around the Vatican, and soon the declaration “We have a pope!” justified the crescendoing ecstasy of their cries.

Galileo, recognizing the potential personal boon of this turn of events, shared his excitement with Suor Maria Celeste by sending her a sheaf of letters that spanned a decade of pleasant exchanges. These dated from Cardinal Barberini’s first letter to Galileo in 1611, when he called him a virtuous and pious man of great value whose longevity could only improve the lives of others. The passing years had fanned the cardinal’s ardor, so that his 1620 poem, “Dangerous Adulation,” not only cited Galileo as the discoverer of wondrous new celestial phenomena but also used his sunspots as a metaphor for dark fears in the hearts of the mighty. In closing the cover letter to Galileo that accompanied this poetic tribute, the cardinal had signed himself—with noteworthy warmth—“as your brother.”

Galileo naturally took a more deferential tone in his responses, noting sentiments such as, “I am your humble servant, reverently kissing your hem and praying God that the greatest felicity shall be yours.” He wrote as often as necessary to keep Cardinal Barberini updated on his scientific work and sent him a copy of each of his books, as well as his unpublished “Treatise on the Tides,” and Guiduccfs

Discourse on the Comets.

The most recent letter from the cardinal bore the date June 24, 1623, just weeks prior to his accession, in which he thanked Galileo for guiding a favorite nephew, Francesco Barberini, through the successful completion of doctoral studies at Pisa.

Galileo wanted nothing so much as to travel to Rome in August to kiss the feet of the new pope and march with his fellow Lyncean Academicians in Urban’s investiture procession. The exciting early days of the Barberini pontificate overflowed with promise for all artists and scientists, and particularly those from Urban’s native Florence. Striking now, Galileo thought he might well secure the pope’s blessing for his own most sensitive projects, and at the same time ensure his son’s future.

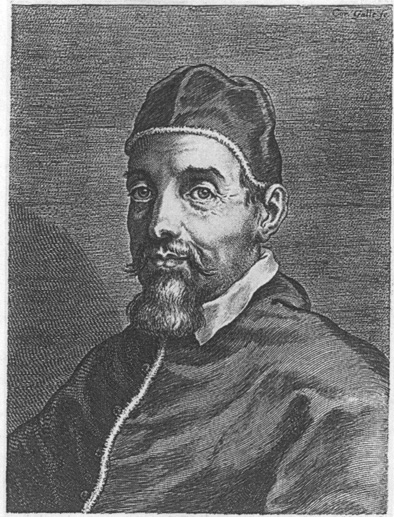

VRBANVS VIII. BARBERINVS PONT. MAX.

Urban VIII in the first year of his pontificate

Galileo had sent Vincenzio off to law school at the University of Pisa the previous year. Now he hoped to obtain a pension for him—a title as a canon that would guarantee Vincenzio a small annual base income for the rest of his life in exchange for little or no real work. Such sinecures influenced the economy of seventeenth-century Italy, often draining the revenues of small dioceses while filling the pockets of absentee landlords, at least half of whom were laymen. Despite the abuses of this system, however, Rome not only tolerated it but also supervised it, because the pensions supported so many more prelates than the papal treasury could afford to pay.

As for Suor Maria Celeste’s request to see a copy of her father’s congratulatory letter to Urban, Galileo denied it on the grounds that he had not written one. He explained to her that although he enjoyed a most cordial relationship of long standing with His Holiness—enabling him to dedicate his new book to the pope and confidently anticipate a private audience at the Vatican—protocol argued against a personal note on this occasion. Instead, he had proffered his congratulations through the proper channel of Urban’s nephew Francesco, who had been Galileo’s student.

“It was through your most gentle and loving letter,” Suor Maria Celeste confessed a few days later, “that I became fully aware of my backwardness, in assuming as I did that you, Sire, would perforce write right away to such a person, or, to put it better, to the loftiest lord in all the world. Therefore I thank you for pointing out my error, and at the same time I feel certain that you will, by the love you bear me, excuse my gross ignorance and as many other flaws as find expression in my character. I readily concede that you are the one to correct and advise me in all matters, just as I desire you to do and would so appreciate your doing, for I realize how little knowledge and ability I can justly call my own.”

The date of this letter, August 13, marked Suor Maria Celeste’s twenty-third birthday, although she made no reference to that fact. She reckoned the accumulation of her years now by the anniversary of her nun’s vows on October 4, and by the feast day of the Holy Virgin Mary, whose name she had taken, on September 8.

Within a week she learned that illness had scotched Galileo’s travel plans and forced him into Florence to the home of his late sister, where his recently widowed brother-in-law and his nephew were taking care of him. The news arrived via the steward of San Matteo, a hired man who lived on the convent grounds with his wife, helping the nuns by tending to the heavy work and the traffic with the outside world.