Galileo's Daughter (16 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

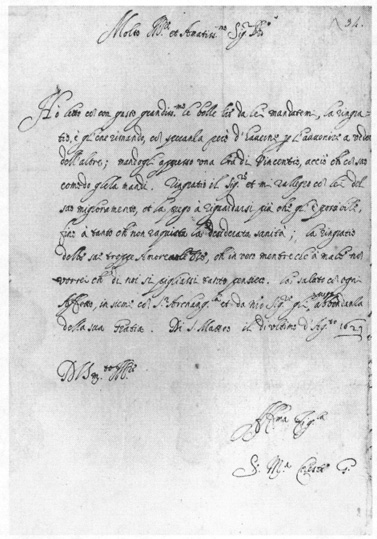

Maria Celeste’s letter of August 31, 1623

Suor Maria Celeste, muscially talented like most members of her family, also directed the choir from time to time and taught the novices how to sing Gregorian chant. In her capacity as the convent’s apothecary, she assisted the visiting doctor, fabricated remedies in pill or tonic form, and nursed the sick nuns in the infirmary, where Suor Arcangela often occupied a bed. Although Suor Maria Celeste, who spoke for both of them in her letters, never directly accused Suor Arcangela of malingering, she sometimes alluded to a hysterical component in her sister’s complaints. The younger daughter’s moodiness and taciturnity may have characterized her nature from childhood. Or the traits may have developed in reaction to cloistered life, which had been her father’s choice and not her own.

The arduous existence of the Poor Clares was described baldly by a contemporary of Suor Maria Celeste’s and Suor Arcangela’s— Maria Domitilla Galluzzi, who entered the house of the Clarisses in Pavia in 1616, and later wrote her own interpretation of the Rule of Saint Clare.

“Show her how we dress in vile clothing,” Maria Domitilla counseled any nun introducing a candidate for admission to the sisters’ way of life, “always go barefoot, get up in the middle of the night, sleep on hard boards, fast continually, and eat crass, poor, and lenten food, and spend the major part of the day reciting the Divine Office and in long mental prayers, and how all of our recreation, pleasure, and happiness is to serve, love, and give pleasure to the beloved Lord, attempting to imitate his holy virtues, to mortify and villify ourselves, to suffer contempt, hunger, thirst, heat, cold, and other inconveniences for his love.”

Although the Council of Trent had specifically denounced the once common practice of forcing young women to take the veil, the percentage of patrician girls entering convents in Florence actually rose through the remainder of the sixteenth century and continued to increase on into the seventeenth. Whether or not Galileo’s daughters walked willingly into San Matteo, Suor Maria Celeste found her place there. The same cannot be said with certainty of Suor Arcangela. If she ever wrote a letter to her father, it has not been preserved.

On top of all her appointed tasks, Suor Maria Celeste voluntarily took up the sort of domestic work she would have performed for her father and brother had she lived in their home on Bellosguardo. Despite her distance, she insinuated herself between the two of them, always placating her father while pleading Vincenzio’s point of view in matters large or small.

“Vincenzio stands in dire want of new collars,” she informed Galileo in an undated letter,

even though he may not think so, as it suits him to have his used ones bleached as the need arises; but we are struggling to accommodate him in this practice, since the collars are truly old, and therefore I would like to make him four new ones with lace trim and matching cuffs; however, since I have neither the time nor the money to do this all by myself, I should like for you to make up what I lack, Sire, by sending me a

braccio

of fine cambric and at least 18 or 20

lire

to buy the lace, which my lady Ortensa makes for me very beautifully; and because the collars worn nowadays tend to be large, they require a good deal of trimming for properly finishing them; moreover, seeing as Vincenzio has been so obedient to you, Sire, in always wearing his cuffs, I maintain, for that reason, he deserves to have handsome ones; and therefore do not be astonished that I ask for this much money.

The wide white collars Suor Maria Celeste sewed, washed, and bleached for her father and brother frame Galileo’s face in every formal portrait painted of him. At home alone, however, tending his experiments or his grapevines, the shirtsleeved Galileo donned an old leather apron.

“I am ashamed that you see me in this clown’s habit,” he reportedly said to a group of distinguished visitors who arrived one afternoon to find him in his garden, in his work clothes. “I’ll go and dress myself as a philosopher.”

But he must have been jesting, for when the men asked Galileo why he didn’t hire someone to take over his manual labor, he replied: “No, no; I should lose the pleasure. If I thought it as much fun to have things done as it is to do them, I’d be glad to.”

This outdoor recreation tempered the concentration of Galileo’s scholarly work and kept him close to Nature. Though the time he spent in his kitchen garden, his orchard, and his vineyard restored his spirits, the hours took their toll on Galileo’s well-worn work garment, which he periodically sent to Suor Maria Celeste for repair.

MOST ILLUSTRIOUS AND BELOVED LORD FATHER

MOST ILLUSTRIOUS AND BELOVED LORD FATHER

I AM RETURNING the rest of your shirts that we have sewn, and the leather apron, too, mended as best I could. I am also sending back your letters, which are so beautifully written that they have only kindled my desire to see more examples of them. Now I am tending to the work on the linens, so that I hope you will be able to send me the trim for borders at the ends, and I remind you, Sire, that the trimmings needs to be wide, because the linens themselves are rather short.

I have just placed Suor Arcangela once more into the doctor’s hands, to see, with God’s help, if she can be relieved of her wearisome illness, which causes me no end of worry and work.

Salvadore [Galileo’s servant] tells me that you want to pay us a visit soon, Sire, which is precisely what we so desire; though I must remind you that you are obliged to keep the promise you made us, that is, to spend an entire evening here, and to be able to have dinner in the convent parlor, because we deliver the excommunication to the tablecloth and not the meals thereon.

I enclose herewith a little composition, which, aside from expressing to you the extent of our need, will also give you the excuse to have a hearty laugh at the expense of my foolish writing; but because I have seen how good-naturedly you always encourage my meager intelligence, Sire, you have lent me the courage to attempt this essay. Indulge me then, Lord Father, and with your usual loving tenderness please help us. I thank you for the fish, and send you loving greetings along with Suor Arcangela. May our Lord grant you complete happiness.

FROM SAN MATTEO, THE 20TH DAY OF OCTOBER 1623.

Most affectionate daughter,

S.M.C.

Suor Maria Celeste’s casual reference to excommunication poked private fun at a practice of the Poor Clares. The Rule of the order stated plainly that no visitors could enter the refectory where the nuns dined. The Convent of San Matteo, however, maintained a separate parlor where a sister’s family members might properly be received. They could bring their own food, too, and share it with her. Thus the dishes themselves, whether cooked in the convent or carried in by the guests, could be eaten with impunity, so long as everyone ate in his or her proper place. A black iron grate, or grille, separated the parlor from the nun’s quarters, and all exchanges passed through the lattice of its bars. Another grille pierced the wall near the altar in the adjacent Church of San Matteo, so that the voices of the nuns singing in their choir could reach the townspeople attending mass on the other side. Although the Poor Clares devoted their earthly lives to praying for all the souls of the world, they required the maintenance of a severed space for this work, where they lived hidden in God’s embrace.

These practices traced back to the early thirteenth century, when Francis of Assisi spurned splendid wealth to found his Order of Friars Minor on the principles of poverty, obedience, and devotion. The rich, privileged young Chiara Offreduccio, or Clare, joined him as his first female follower in the spring of 1212. Francis cut off her golden hair and sent her begging in the streets of Assisi. In time the two divided their labors so that Francis traveled widely preaching the Gospel, while Clare headed the contemplative second order of Franciscans, known as the Clarisses, or Poor Ladies— the Poor Clares. Clare sequestered herself for life in the convent Francis built her at San Damiano, where she slept on the floor and ate practically nothing. She also initiated the tradition of work in the convents, filling the hours between the daily offices with spinning and embroidery.

The Sisters to whom the Lord has given the grace of working should

labor faithfully and devotedly after the hour of Terce at work which

contributes to integrity and the common good . . .

in such a way

that, while idleness, the enemy of the soul, is banished, they do not

extinguish the spirit of holy prayer and dedication to which all

other temporal things should be subservient,

[RULE OF SAINT CLARE,

chapter VII

]

By the time Suor Maria Celeste joined the order, the Rule of Saint Clare had relaxed on some issues and tightened on others, as dictated by Church policy and the individual interpretation of each convent’s mother abbess. Seventeenth-century parents, for example, paid dowries for their daughters to enter Clarisse convents in Italy—a requirement that might have horrified Francis and Clare. Poverty remained a central tenet of the Rule, rendering all Poor Clares dependent on alms. Suor Maria Celeste perforce appealed frequently to her father for financial help, though she found this duty embarrassing. It was one thing to request money to buy presents for Vincenzio and quite another to ask anything for herself. In the “little composition” she apologetically enclosed with her letter of October 20, she apparently meant to soften her current plea by making a comedy of the convent’s neediness. Unfortunately, the attachment has disappeared, so it is impossible to say whether it took the form of an essay or perhaps a dramatic action of the sort Galileo used to write—and liked to see performed, through the grille, when he visited San Matteo. The nuns also wrote plays, in keeping with convent traditions, for the Church authorities encouraged them to stage spiritual comedies and tragedies drawn from biblical themes as part of their education and recreation.

Saint Clare

Whatever Suor Maria Celeste’s request, Galileo never failed to fulfill it, precipitating a flood of appreciation in return. Suor Maria Celeste’s word for the loving indulgence that characterized her father’s attentiveness—

amorevolezza

—appears more than twenty times in her 124 surviving letters, thanking him for some recent act of thoughtfulness or generosity toward herself, her sister, or someone else in the convent. Thus, all the while that Galileo was inventing modern physics, teaching mathematics to princes, discovering new phenomena among the planets, publishing science books for the general public, and defending his bold theories against establishment enemies, he was also buying thread for Suor Luisa, choosing organ music for Mother Achillea, shipping gifts of food, and supplying his homegrown citrus fruits, wine, and rosemary leaves for the kitchen and apothecary at San Matteo.