Galileo's Daughter (38 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

FROM SAN MATTEO, THE 2ND DAY OF JULY 1633.

Most affectionate daughter,

Galileo’s humiliation spread outward from Rome as fast as messengers could carry the news. At the pope’s command, and with fanfare, the text of Galileo’s mortifying sentence was posted and read aloud by inquisitors from Padua to Bologna, from Milan to Mantua, from Florence to Naples to Venice and on to France, Flanders, and Switzerland, alerting the professors of philosophy and mathematics at each locale of the outcome of Galileo’s affair. In Florence in particular, instructions called for the condemnation to occasion a plenary session of the Florentine Inquisition, to which as many mathematicians as possible should be invited.

In the summer of 1633, spurred by these events, a lively black market trade sprang up around the banned

Dialogue.

The price of the book, which had originally sold for half a

scudo,

rose to four and then to six

scudi

as priests and professors across the country purchased copies to keep the inquisitors from cornering the market. A Paduan friend of Galileo’s wrote to tell him how the well-known university philosopher Fortunio Liceti had actually surrendered his copy to the authorities, as though this were a most singular aberrant act, and no one else who owned the

Dialogue

could bear to part with it. As the book grew in esteem among Galileo’s cohorts, it also gained new converts.

Sometime later that July or August, a messenger smuggled a copy of the

Dialogue

across the Alps, with the help of clandestine agents, to Strasbourg, where the Austrian historian Mathias Berneggar began to prepare a Latin translation that would be ready for general distribution throughout Europe by 1635. In 1661, an English version of the

Dialogue

appeared, translated by Thomas Salusbury. The prohibition of the book by the Index endured for a long time, but not with a long arm outside Italy.

In 1744, publishers in Padua gained permission to include the

Dialogue

in a posthumous collection of Galileo’s works, by inserting appropriate qualifying remarks and disclaimers in the text. But this concession did not lead to any rapid relaxation of the ruling against the

Dialogue,

which remained officially prohibited. On April 16, 1757, when the Congregation of the Index withdrew its general objections against books teaching the Copernican doctrine, it specifically cited the

Dialogue

as a still-forbidden title. The

Dialogue

in fact stayed banned for another sixty-five years, until 1822, when the Congregation of the Holy Office decided to allow publication of books on modern astronomy expounding the movement of the Earth. No new Index, however, was issued at the time to reflect this change in attitude. Thus the 1835 edition became the first Index in almost two centuries to drop the listing of the

Dialogue of Galileo Galilei.

At Siena

Not knowing

how to

refuse him

the keys

In framing Galileo’s trial as a simplistic case of science versus religion, anti-Catholic critics have claimed that the Church opposed a scientific theory on biblical grounds, and that the outcome mocked the infallibility of the pope. Technically, however, the anti-Copernican Edict of 1616 was issued by the Congregation of the Index, not by the Church. Similarly, in 1633, Galileo was tried and sentenced by the Holy Office of the Inquisition, not by the Church. And even though Pope Paul V approved the Edict of 1616, just as Pope Urban VIII condoned Galileo’s conviction, neither pontiff invoked papal infallibility in either situation. The freedom from error that belongs to the pope as his special privilege applies only when he speaks as shepherd of the Church to issue formal proclamations on matters of faith and morals. What’s more, the right of infallibility was never formally defined in Galileo’s time, but issued two centuries later from Vatican Council I, held in 1869-70.

Although Urban personally believed in his own power enough to boast that the sentence of one living pope—namely Urban himself— outweighed all the decrees of one hundred dead ones, he refrained from claiming infallibility in the Galileo case.

French philosopher Rene Descartes, who followed Galileo’s trial from his home in Holland, understood these distinctions. Thus Descartes could comment hopefully to a colleague: “As I do not see that this censure has been confirmed either by a Council or by the Pope, but proceeds solely from a committee of cardinals, it may still happen to the Copernican theory as it did to that of the antipodes [the eighth-century censured notion of a sub-Earth Earth with human inhabitants] which was once condemned in the same way.” Nevertheless Descartes, a product of his Jesuit education and a devout Catholic throughout his life, withheld from publishing the book he himself had just completed,

Le Monde,

which espoused Copernicus’s view of the universe.

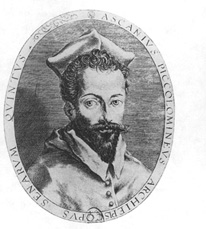

Numerous churchmen, however—including highly placed clerics such as Ascanio Piccolomini, the archbishop of Siena—had endorsed Galileo’s

Dialogue

from their initial reading of it and continued to consider the author their friend. “It seems exceeding strange to me,” Archbishop Piccolomini had written to Galileo when the outcry over the

Dialogue

first arose, “that such a recent and precise approbation should be opposed by the passions of some people who might find fault only in what they conceive of the book, for the work itself ought to appease the most timid conscience. On the other hand, I will say you deserve this and worse, for you have been disarming by steps those who have control of the sciences, and they have nothing left but to run back to holy ground.”

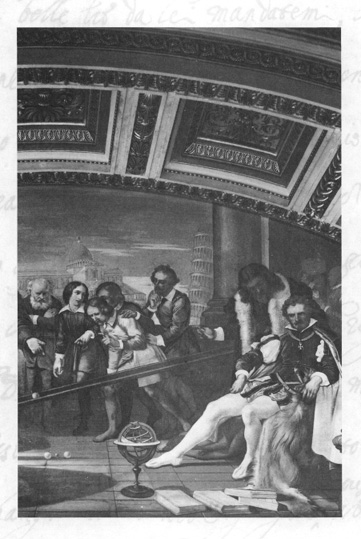

Archbishop Piccolomini, capping a long line of scholars from a distinguished family that produced two popes, had himself studied mathematics and been Galileo’s admirer for many years. Now, in the aftermath of the trial, Piccolomini assumed custody of Galileo, who left the Tuscan embassy in Rome on July 6 and arrived at the archiepiscopal palace, immediately adjacent to the magnificent domed cathedral of Siena, three days later on July 9.

Ascanio Piccolomini, Archbishop of Siena

If Galileo looked “more dead than alive,” as Ambassador Niccolini had described him when he returned from his April questioning by the Holy Office, how must he have appeared at Siena in July, after these many more weeks and traumas? The injustice of the sentence tormented him so that he did not sleep for several nights but could be heard crying out, babbling and rambling in distraction. The archbishop feared for his safety to the point where he considered binding Galileo’s arms to keep him from accidentally injuring himself in bed. Piccolomini determined to restore the man’s broken spirit and return his thoughts to scientific pursuits. The fact that Galileo was able to rise from the ashes of his condemnation by the Inquisition to complete another book project (and for this last work to prove his greatest original contribution) is due in large measure to Piccolomini’s solicitous kindness. A French visitor to Siena in 1633, the poet Saint-Amant, reported finding the archbishop and Galileo together among the rich tapestries and furnishings that filled the guest apartment at the palace, engaging each other in discussion of a mechanical theory, which lay partially written on pages spread all around them.

MOST ILLUSTRIOUS AND BELOVED LORD FATHER

MOST ILLUSTRIOUS AND BELOVED LORD FATHER

THAT THE LETTER YOU WROTE me from Siena (where you say you find yourself in good health) brought me the greatest pleasure, and the same to Suor Arcangela, is needless for me to weary myself in convincing you, Sire, since you will well know how to fathom what I could not begin to express; but I should love to describe to you the show of jubilation and merriment that these mothers and sisters made upon learning of your happy return, for it was truly extraordinary; since the Mother Abbess, with many others, hearing the news, ran to me with open arms, and crying with tenderness and happiness; truly I am bound as a slave to all of them, for having understood from this display how much love they feel for you, Sire, and for us.

Hearing furthermore that you are staying in the home of a host as kind and courteous as Monsignor Archbishop multiplies the pleasure and satisfaction, despite the potential prejudicial effect this may have on our own interests, because it could well prove to be the case that his extremely enjoyable conversation may engage and detain you much longer than we would like. However, since here for now the suspicions of contagion continue, I commend your remaining there and awaiting (as you say you wish to do) the safety assurance from your closest friends, who, if not with greater love, at least with more certainty than we possess, will be able to apprise you of the facts.

But meanwhile I should judge that it would be wise to draw a profit from the wine in your cellar, at least one cask’s worth; because although for now it is keeping well, I fear this heat may precipitate some peculiar effect: and already the cask that you had tapped before you left, Sire, from which the housemaid and the servant drink, has begun to spoil. You will need to give orders as to what you want done, because I have so little knowledge of this business; but I am coming to the conclusion that since you produced enough to last the entire year, and as you have been away for six of those months, you will still have plenty left, even if you should return in a few days.

Leaving this aside, however, and turning to that which concerns me more, I am longing to know in what manner your affair was terminated to the satisfaction of both you and your adversaries, as you intimated in the next to last letter you wrote me from Rome: tell me the details at your convenience, and only after you have rested, because I can be patient a while longer awaiting enlightenment on this contradiction.

Signor Geri was here one morning, during the time we suspected you to be in the greatest danger, Sire, and he and Signor Aggiunti went to your house and did what had to be done, which you later told me was your idea, seeming to me at the time well conceived and essential, to avoid some worse disaster that might yet befall you, wherefore I knew not how to refuse him the keys and the freedom to do what he intended, seeing his tremendous zeal in serving your interests, Sire.