Galileo's Daughter (41 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

If ever I fail to make a great demonstration of the desire I harbor for your return, I refrain only to avoid goading you too much or disquieting you excessively. Rather than take that risk, all through these days I have been building castles in the air, thinking to myself, if, after these two months of delay in not obtaining the favor of your release, I had been able to appeal to Her Ladyship the Ambassadress, then she, working through the sister-in-law of His Holiness, might have successfully implored the Pope on your behalf. I know, as I freely admit to you, that these are poorly drawn plans, yet still I would not rule out the possibility that the prayers of a pious daughter could outweigh even the protection of great personages. While I was wandering lost in these schemes, and I saw in your letter, Sire, how you imply that one of the things that fans my desire for your return is the anticipation of seeing myself delighted by a certain present you are bringing, oh! I can tell you that I turned truly angry; but enraged in the way that blessed King David exhorts us in his psalm where he says,

Irascimini et nolite peccare

[Be angry, but sin not]. Because it seems almost as though you are inclined to believe, Sire, that the sight of the gift might mean more to me than that of you yourself: which differs as greatly from my true feelings as the darkness from the light. It could be that I mistook the sense of your words, and with this likelihood I calm myself, because if you questioned my love I would not know what to say or do. Enough, Sire, but do realize that if you are allowed to come back here to your hovel, you could not possibly find it more derelict than it is, especially now that the time approaches to refill the casks, which, as punishment for the evil they committed in allowing the wine to spoil, have been hauled up onto the porch and there staved in according to the sentence pronounced on them by the most expert wine drinkers in these parts, who point out as the primary problem your practice, Sire, of never having broken them open before, and the same experts claim the casks cannot suffer now for having had some sunshine upon their planks.

I received 8

scudi

from the sale of the wine, of which I spent 3 on six

staia

of wheat, so that, as the weather turns cooler, La Piera may return to her bread baking; La Piera sends her best regards to you, and says that if she were able to weigh your desire to return against her longing to see you, she feels certain her side of the scale would plummet to the depths while yours would fly up to the sky: of Geppo there is no news worthy of mention. Signor Rondinelli this week has paid the 6

scudi

to Vincenzio Landucci and has retained two receipts, one for last month, one for this: I hear that Vincenzio and the children are healthy, but I do not know how they are getting along, not having been able to inquire after them from a single person.

I am sending you another batch of the same pills, and I greet you with all my heart together with our usual friends and Signor Rondinelli. May Our Lord bless you.

FROM SAN MATTEO, THE 20TH DAY OF AUGUST 1633.

Most affectionate daughter,

Recitation

of the

penitential

psalms

Galileo in siena reconvened his three familiar characters— Salviati, Sagredo, and Simplicio—and let them take up the discussion of his

Two New Sciences.

The banning of the

Dialogue

had destroyed his literary monument to the memory of those long-gone friends, and so, although Galileo had no idea whether he would be allowed to publish another book, he began to put his accumulated material on motion into their mouths. He composed the dialogue for the first two of his three interlocutors’ four new days together during his five-month stay at the archbishop’s house.

In the initial excitement of greeting one another again, the three companions flood their talk with speculations on how to measure the speed of light or the weight of air, and how patterns of waves create consonance or dissonance in music. But their voices have changed since last they met. It is as though—it must be

because

— all three have lived through Galileo’s tribulations with him and lost their verve. Salviati is not as persuasive, Sagredo not as passionate, Simplicio not nearly as stubbornly opposed to novelty. In lieu of the sarcastic barbs and literary devices that animated the

Dialogue,

the men trade polite lines to maintain the dramatic form, but not the flare, of the previous book. On the third and fourth days, they open their Italian dialogue to Salviati’s reading aloud an entire Latin treatise on motion written by “our Academician,” as they like to call Galileo. These sections, dense as any geometry textbook, almost immediately lose the casual reader in a forest of propositions and theorems, though they embody Galileo’s seminal restructuring of physics as a science based on mathematics.

Instead of Sagredo’s palazzo on the Grand Canal, Galileo staged the trio’s reunion at the great shipworks of the Venice Arsenale, where they could draw inspiration from the sight of men and machines at work. “The constant activity which you Venetians display in your famous Arsenale,” Salviati exclaims in his opening speech, “suggests to the studious mind a large field for investigation, especially that part of the work which involves mechanics.”

The Venetian Arsenale

An experienced artisan at the shipyard immediately sets them off with his remark that extra care must be taken in the launching of the largest vessels, so as to avoid the peril of the big ships’ splitting apart under their own great weight. Sagredo thinks this explanation strains belief. Though it is “proverbial and commonly accepted,” he says, that large structures are weaker than small, “I hold it to be altogether false, like many another saying which is current among the ignorant.”

Sagredo’s doubt gives Salviati a chance to reveal the wisdom of the old workman’s words, supported by “our friend” Galileo’s mathematical demonstrations regarding relative size and strength of materials—the first of the two “new sciences” in the book’s title. (The second, motion, including free fall and the paths of fired projectiles, would be covered on Days Three and Four.)

“Please observe, gentlemen,” Salviati responds,

how facts which at first seem improbable will, even on scant explanation, drop the cloak which has hidden them and stand forth in naked and simple beauty. Who does not know that a horse falling from a height of three or four

braccia

will break his bones, while a dog falling from the same height or a cat from eight or ten, or even more, will suffer no injury? Equally harmless would be the fall of a grasshopper from a tower or the fall of an ant from the distance of the Moon. Do not children fall with impunity from heights which would cost their elders a broken leg or perhaps a fractured skull? And just as smaller animals are proportionately stronger and more robust than the larger, so also smaller plants are able to stand up better than larger. I am certain you both know that an oak two hundred feet high would not be able to sustain its own branches if they were distributed as in a tree of ordinary size; and that Nature cannot produce a horse as large as twenty ordinary horses, or a giant ten times taller than an ordinary man, unless by miracle or by greatly altering the proportions of his limbs and especially of his bones, which would have to be considerably enlarged over the ordinary. Likewise the current belief that, in the case of artificial machines the very large and the small are equally feasible and lasting is a manifest error.

The diagrams and geometrical proofs that follow show how volume outstrips strength as things get bigger: Volume expands as the cube of bodies’ dimensions, while strength increases only as much as their square.

“I am quite satisfied,” declares Simplicio toward the end of the first day, “and you may both believe me that if I were to begin my studies over again, I should try to follow the advice of Plato and commence from mathematics, which proceeds so carefully, and does not admit as certain anything except what it has conclusively proved.”

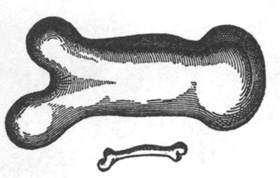

Galileo’s comparative

bone drawing from

Two New Sciences

On Day Two, when the discussion becomes more mathematical and even more dependent upon diagrams, Salviati elaborates on problems of scale by drawing a couple of bones. One appears to be a femur from a dog. The other looks like a gross, bloated distortion of the same. “To illustrate briefly,” Salviati says,

I have sketched a bone whose natural length has been increased three times and whose thickness has been multiplied until, for a correspondingly large animal, it would perform the same function which the small bone performs for its small animal. From the figures here shown you can see how out of proportion the enlarged bone appears. Clearly then if one wishes to maintain in a great giant the same proportion of limb as that found in an ordinary man he must either find a harder and stronger material for making the bones, or he must admit a diminution of strength in comparison with men of medium stature; for if his height be increased inordinately he will fall and be crushed under his own weight. Whereas, if the size of a body be diminished, the strength of that body is not diminished in the same proportion; indeed the smaller the body the greater its relative strength. Thus a small dog could probably carry on his back two or three dogs of his own size; but I believe that a horse could not carry even one horse of his own size.

“I am delighted to hear of your good health and peace of mind,” Suor Maria Celeste wrote in response to one of Galileo’s progress reports on

Two New Sciences,

“and that your pursuits are so well suited to your tastes, as your current writing seems to be, but for love of God may these new subjects not chance to meet the same luck as past ones, already written.”

Because of the subjects he had treated in his

Dialogue,

Galileo was now expected to perform penance as part of the process of contrition. The Holy Office had enjoined him to recite the seven penitential psalms once a week for three years, to aid his rehabilitation. Saint Augustine, around the dawn of the fifth century, had selected these particular psalms for daily study and prayer in trying times, as a way to guard and greaten one’s faith.

O

Lord, rebuke me not in thine anger, neither chasten me in thy

hot displeasure.

Have mercy upon me, O Lord; for I am weak: O Lord, heal me; for

my bones are vexed. [6:1, 2]

The sacrament of penance, which the Protestants had rejected during the Reformation, increased in importance in seventeenth-century Italy after the Council of Trent. The penitent was required to reconcile himself with God and the Church by performing three kinds of acts: contrition, confession, and satisfaction. Galileo had already expressed his contrition and confessed publicly by abjuration. He most likely confessed in private and in confidence to an individual priest as well, although there is no evidence—of necessity there would be no evidence—that he did so. Even though the council’s decrees stipulated only a single confession annually, at Eastertide, a new spiritual emphasis on the introspective examination of conscience compelled many Catholics to confess their sins as often as once a month.