Galileo's Daughter (26 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

immortalige your fame

By the time Galileo finished writing his book about the world systems, just as December 1629 drew to a close, he had established a new closeness with his daughter. Ever a source of love and financial aid to Suor Maria Celeste, as well as the grateful recipient of her labors, he now began to do favors for her that required the skilled work of his own hands. And she, emboldened either by her recent assistance on the manuscript for the

Dialogue

or by the maturity of her nearly thirty years, engaged her father with increased confidence. Before too long, the strength of their mutual affection and deepening interdependence would submit to tests neither one of them could yet imagine.

Having moved into her private room, Suor Maria Celeste found it spacious enough to accommodate a small party of sisters at afternoon needlework. The single, small, high window, however, admitted only a dim light, and so she asked Galileo if she might send him the window frames to be refitted with newly waxed linen. “I do not doubt your loving willingness in this matter,” she said of her request, “but the fact that the work is rather more suited to a carpenter than a philosopher gives me pause.”

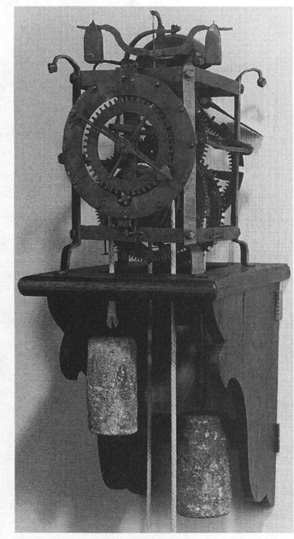

Convent clock of the type used at San Matteo

She also prevailed on him several times to repair the convent’s temperamental clock. He fixed it once when its chime failed to wake the sacristan (who in turn failed to summon the other sisters from sleep to the Midnight Office) and again whenever it developed a different quirk. “Vincenzio worked on our clock for a few days, but since then it sounds worse than ever,” she told Galileo on January 21, 1630. “For my part, I would judge the defect to be in the cord, which, owing to its being old, no longer glides. Still, as I am unable to fix it, I turn it over to you, so that you can diagnose its deficiency, and repair it. Perhaps the real defect was with me, in not knowing the right action to take, which is the reason I have left the counterweights attached this time, suspecting that perhaps they are not in their proper place; in any event I beseech you to send it back as quickly as you possibly can, because otherwise these nuns will not let me live.”

Galileo’s brother, Michelangelo, had purchased the convent’s portable clock, which stood about two feet tall, in Germany. Like all mechanical timekeepers of its day, this one offered no precision improvement over the sundial, though it did mark time through the dark or the rain and strike the hour aloud.

Italians numbered the hours of the seventeenth century from one to twenty-four, beginning at sunset, so that if Suor Maria Celeste told her father she was “writing at the seventh hour,” she meant she worked far into the night. And when she reported the death of an ailing nun “at the fourteenth hour” of a November Sunday, the time indicated was about half past six in the morning.

“The clock that traveled back and forth between us so many times now runs beautifully,” Suor Maria Celeste said in a thank-you note on February 19, “its flaw having been my fault, as I adjusted it improperly; I sent it to you in a covered basket with a towel, and have not seen either of these since; if you find them by chance about your house, Sire, please do return them.”

*

As he performed these services, Galileo initiated the rigmarole of licensing and printing his recently completed book. Since Prince Cesi of the Lyncean Academy intended to publish the

Dialogue

in Rome, the work would have to undergo censorship there in the Holy City, despite the fact that its author lived in Florence. Galileo, now almost sixty-six, planned personally to deliver the manuscript to the relevant authorities at the Vatican. But Rome was a distant country, and an old man risked his life adding wintry weather to the perils inherent in a two-hundred-mile journey.

In February, while Galileo waited for spring, Pope Urban VIII unexpectedly issued a formal salute to his “honest life and morals and other praiseworthy merits of uprightness and virtue.” With these words Urban gave Galileo a prebend in Pisa—similar but unrelated to the previously granted canonry at Brescia, which had bounced from Vincenzio to Vincenzio and then out of the Galilei family bounds. Rather than accept the Pisan prebend right away, however, Galileo tried instead to reclaim the Brescian one, now that its incumbent had died, for his infant grandson.

“I do not think it would be possible to confer this pension on a baby without a dispensation which will be very difficult to obtain,” Galileo’s old friend Benedetto Castelli counseled him on the matter. (After nearly a year’s maneuvering, Galileo himself emerged as canon of Brescia

and

canon of Pisa—with a combined annual annuity of one hundred

scudi

from church revenues. While his clerical posts did not require him to wear a habit or change his lifestyle, he did have his head shaved in an ecclesiastical tonsure by the bishop of Florence.)

Mid-March turned Galileo’s thoughts toward Rome and his impending departure to procure the printing license for the

Dialogue.

His typical devotion to scholarly pursuits at this point raised the usual concerns in Suor Maria Celeste. “And I would not want you, while seeking to immortalize your fame,” she fretted in an April letter, “to cut short your life; a life held in such reverence and treasured so preciously by us your children, and by me in particular. Because, just as I have precedence over the others in years, Sire, so too do I dare to claim that I precede and surpass them in my love for you.”

Galileo gathered the whole family, including Vincenzio and the again-pregnant Sestilia, at the convent’s parlor grille on the morning of April 15 to say good-bye. By May 3, he had arrived at the Tuscan embassy in Rome, where he lodged for the next two months as the guest of Ambassador Francesco Niccolini and his charming wife, Caterina. Not only did Galileo enjoy their hospitality, but he also prized their connections at the Vatican: Her Ladyship the Ambassadress was a close cousin to the Dominican father Niccolo Riccardi, who controlled the Roman licensing of books. Technically Pope Urban, as bishop of Rome, owned this and all other ecclesiastic powers pertaining to the stewardship of the city. But since the pope’s diocese encompassed the world, he delegated most local affairs to his cardinal vicar, and the censorship of books to his master of the Sacred Palace. Father Riccardi bore this important title, although his cousins at the embassy affectionately called him “Father Monster”—a nickname he had earned from King Philip III of Spain, in recognition of his imposing physical proportions and mental prowess.

Galileo could not have handpicked a more favorable judge than Father Riccardi. The man came from a fine Florentine family closely allied with the Medici, and he had greeted Galileo’s previous work,

The Assayer,

with a gush of admiration. “Besides having found here nothing offensive to morality,” Father Riccardi stated in

The Assayer

s imprimatur in 1623, “nor anything which departs from the supernatural truth of our faith, I have remarked in it so many fine considerations pertaining to natural philosophy that I believe our age is to be glorified by future ages not only as the heir of works of past philosophers but as the discoverer of many secrets of nature which they were unable to reveal, thanks to the deep and sound reflections of this author in whose time I count myself fortunate to be born—when the gold of truth is no longer weighed in bulk and with the steelyard, but is assayed with so delicate a balance.”

Ambassador Niccolini nevertheless took a grim view of the road ahead. He sent word to the grand duke in Florence that he expected trouble because of Galileo’s numerous, vociferous enemies, particularly among the Jesuits, who were already criticizing both the premise of the new book and its author. Reliable rumors ran through Rome, alleging how the

Dialogue

explained the tides by the motion of the Earth. Theologians naturally frowned on such a notion.

Father Riccardi read the book himself. He also deputized a fellow Dominican with expertise in mathematics to scrutinize the text and report back to him. Meanwhile, Galileo facilitated a friendship by correspondence between his elder daughter and his kind hostess, Caterina Riccardi Niccolini, for he saw Her Ladyship the Ambassadress as a potential patroness for the sisters of San Matteo.

“The Mother Abbess sends her regards to you, Sire,” Suor Maria Celeste wrote at the end of May,

and reminds you of what she told you in person: that is, if chance should offer you the opportunity there in Rome to obtain some charitable help for our Monastery, to please extend yourself in this effort for the love of God and for our relief; although I must add that truly it seems an extraordinary thing to ask of people living so far away, who, when doing a good deed for someone, would prefer to favor their own neighbors and compatriots. Nonetheless I know that you know, Sire, by biding your time, how to pick the perfect moment for implementing your intentions successfully; and therefore I eagerly encourage you in this endeavor, because indeed we really are in dire need, and if it were not for the help we have received from several donations of alms, we would be at risk of starving to death.

During the eight weeks Galileo spent in Rome, Pope Urban granted him only one gracious audience. His Holiness had no time for more. The past several years had enmeshed him in difficult papal affairs, including political machinations pertaining to the Thirty Years’ War. What had begun as a battle between German Catholics and German Protestants had pulled into its vortex kings and princes of many other countries, including France, Spain, Portugal, Denmark, Sweden, Poland, Transylvania, and Turkey—all contributing to the carnage on German soil. By 1630, only a few of the multiple causes fueling the ongoing fighting still pertained to issues of religious faith; one of these was the struggle between the Catholic royal families of France and Spain for control of the Catholic throne of the Holy Roman emperor in Germany. The pope, as the leader of all Catholics everywhere, might have tried harder to unite the Spanish Hapsburgs and the French Bourbons. But instead, Urban, who had served early in his Church career as papal legate in France, where he held the newborn Louis XIII at the baptismal font, allied himself with King Louis and Cardinal Richelieu. Of late, Urban had grown so fearful of Spanish spies in the Vatican, he complained, that he dared not speak above a whisper. The Pontiff’s war worries so disrupted his sleep that he ordered all the birds in his gardens killed, lest they offend him with nocturnal calls.

In addition to the Thirty Years’ War, Urban entered the War of the Mantuan Succession, which broke out in northern Italy in 1627. In the strategically located Duchy of Mantua, in Lombardy, an aged duke and his brother both met their deaths without having produced the obligatory male heir.

*

In 1625, the dying duke had installed a French relative in his Italian office, hoping to keep the property in the family, but a bloody dispute erupted over Mantua that reflected the general tension between France and Spain for an Italian foothold. Urban contributed military support to Mantua and made new enemies among the citizens of Rome by taxing them to help pay the high cost of equipping seven thousand infantrymen and eight hundred cavalry.

Meanwhile, Austrian Hapsburg troops fighting in Mantua inadvertently released a biological weapon along with their musket fire, by carrying the bubonic plague across the Alps into Italy in 1629. Urban, as part of his program to protect the populace from this threat, now traveled clear across Rome every Sunday to say mass at the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore, where a treasured image of the Madonna had miraculously barred the plague from the city in the sixth century.

Adding to Urban’s woes, an astrological forecast in the spring of 1630 prophesied his own early demise. The superstitious pontiff retaliated first with imprisonment for the astrologer and later with a ferocious edict prohibiting predictions of a pope’s death, or even the deaths of papal family members up to and including the third degree of consanguinity. Urban’s consistent concern for the male members of the Barberini line manifested itself in a perpetual stream of promotions and pensions. The pope had all but dragged his brother Antonio, a Capuchin monk, away from the simple devotional life at the monastery to become a cardinal in the papal court in 1624. He later made another cardinal of his nephew Antonio in 1628, though the youth (the baby brother of the cardinal nephew Francesco) was only nineteen. Urban designated the middle child among his three nephews, Taddeo, to father the next generation of Barberinis, and married him into a family of landed, titled Roman gentry.

Urban had continued all the while to indulge his own intellect by writing and publishing epic poetry. He had also reformed the breviary—the religious orders’ handbook of prayers, offices, hymns, saints, and instructional passages from the Bible—by adding his own original hymnal compositions in honor of the saints he had canonized. And then, wishing to bring the existing, mostly ancient hymns in the old breviary up to his high standards, Urban had commissioned a cadre of literary Jesuits to edit them for grammar and meter.