Galileo's Daughter (27 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

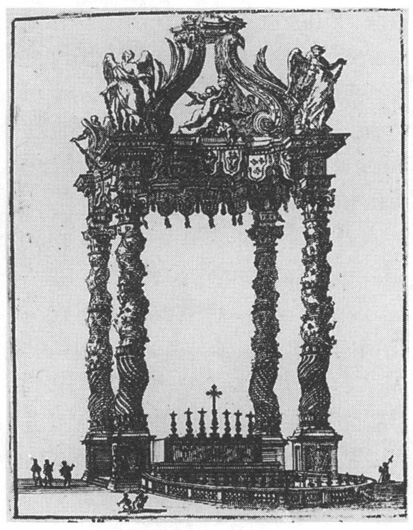

He had further sought to ensure the immortality of his name through the construction of an ornate bronze canopy above the tomb of Saint Peter inside the Vatican basilica. In 1624, soon after his election, Urban charged the sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini to begin building this

baldacchino,

or arch, over the altar where only the pope himself was permitted to preside. By the time of Galileo’s 1630 visit to Rome, the

baldacchino

’s mammoth form was rising inside the church from four marble cornerstones, each emblazoned on two sides with the Barberini three-bee coat of arms. Four support pillars spiraled ninety-five feet up toward the canopy, to be crowned by a cross of gold and a coterie of carved angels. The bronze pillars contained beams lifted from the Pantheon, an enormous ancient structure that had survived the sack of Rome by barbarians in the fifth century. When Urban ordered the venerable Pantheon looted for his armaments’ and monument’s sake, outraged Romans plaintively played on his name: “What the barbarians did not do,” they cried, “the Barberini did.”

Everywhere Galileo looked in Rome, he saw evidence of Urban’s aggrandizement. Although the Tuscan philosopher remained in the pope’s favor—as the recent prebend and the private audience attested—he could no longer expect the same degree of personal contact that had been his privilege in the past. Galileo saw no reason to feel slighted by this change, however, especially when invited to dine as the special guest of the cardinal nephew, and when told how Father Riccardi was discussing the details of his

Dialogue

in closed session with His Holiness.

Baldacchino designed by Bernini for Pope Urban VIII

On June 16 Galileo found out that the

Dialogue

had passed the reviewer’s inspection. Within days Father Riccardi signed the manuscript, giving Galileo a provisional license to publish in exchange for the promise of a few corrections. The title, for example, displeased the pope with its allusion to the physical phenomenon of the tides. Galileo had to choose a more mathematical or hypothetical title. Also the preface and ending must support the pope’s philosophy of science, which attributed all complexity in Nature to the mysterious omnipotence of God. In any event, preliminary negotiations with printers regarding the

Dialogue

could now begin.

Satisfied, Galileo rushed to leave the city by the end of June, before the plague or malaria wafted into Rome on the summer heat. He promised Father Riccardi he would write the necessary corrections back home at Bellosguardo and then return with the revised manuscript in autumn.

“Had the season been different I would have stayed to have it printed,” he explained later that summer to a correspondent in Genoa, “or else left it in the hands of Prince Cesi, who would take care of it as he has done other works of mine; but he was ill, and what is worse I now understand he is near death.”

Indeed, the good Prince Cesi passed away on August 1, at forty-five, killed by gangrene of the bladder. His loss all but dissolved the Lyncean Academy. With Cesi gone, Galileo realized he would have to supervise publication of the

Dialogue

himself. And in that case he hoped to avoid trekking back and forth to Rome any longer, but to try instead to procure a license from local authorities in Tuscany.

Before he could put this plan into effect, however, the deadly plague that had spread through Milan and Turin over the past year moved south to invade the city of Florence. Soon, stricken families on both sides of the Arno mourned new victims of the pestilence at every hour. Up on the hill at Bellosguardo, one of Galileo’s craftsmen, a glassblower, died with his skin discolored by blackish splotches and a putrid bubo festering in his groin.

Since the

lord chastises

us with

these whips

MOST BELOVED LORD FATHER

I am heartsick and worried, Sire, imagining how disturbed you must be over the sudden death of your poor unfortunate worker. I assume that you will use every possible precaution to protect yourself from the danger, and I fervently urge you to make great effort in this endeavor; I further believe that you possess remedies and preventatives proportionate to the present threat, wherefore I promise not to dwell on the subject. But still with all due respect and filial confidence I will exhort you to procure the best remedy of all, which is the grace of blessed God, by means of a thorough contrition and penitence. This, without doubt, is the most efficacious medicine, not only for the soul, but for the body as well: since, given that living happily is so crucial to the avoidance of contagious illness, what greater happiness could one secure in this life than the joy that comes of a clear and calm conscience?

It is certain that when we possess this treasure we will fear neither danger nor death; and since the Lord justly chastises us th these whips, we try, with His aid, to stand ready to receive he blow from that mighty hand, which, having magnanimously granted us the present life, retains the power to deprive us of it at any moment and in any manner.

Please accept these few words proffered with an overflowing heart, Sire, and also be aware of the situation in which, by the Lord’s mercy, I find myself, for I am yearning to enter the other life, as every day I see more plainly the vanity and misery of this one: in death I would stop offending blessed God, and I would hope to be able to pray ever more effectively, Sire, for you. I do not know but that this desire of mine may be too selfish. I pray the Lord, who sees everything, to provide through His compassion what I fail to ask in my ignorance, and to grant you, Sire, true consolation.

All of us here are in good physical health, save for Suor Violante, who is little by little wasting away: although indeed we are burdened by penury and poverty, which take their toll on us, still we are not made to suffer bodily harm, with the help of the Lord.

I am eager to know if you have had any response from Rome, regarding the alms you requested for us. Signor Corso [Suor Giulia’s brother] sent a weight of silk totaling 15 pounds, and Suor Arcangela and I have had our share of it.

I am writing at the seventh hour: I shall insist that you excuse me if I make mistakes, Sire, because the day does not contain one hour of time that is mine, since in addition to my other duties I have now been assigned to teach Gregorian chant to four young girls, and by Madonna’s orders I am responsible for the day-to-day conducting of the choir: which last creates considerable labor for me, with my poor grasp of the Latin language. It is certainly true that these exercises are very much to my liking, if only I did not also have to work; yet from all this I do derive one very good thing, which is that I never ever sit idle for even one quarter of an hour. Except that I require sufficient sleep to clear my head. If you would teach me the secret you yourself employ, Sire, for getting by on so little sleep, I would be most grateful, because in the end the seven hours that I waste sleeping seem far too many to me.

I shall say no more so as not to bore you, adding only that I give you my loving greetings together with our usual friends.

FROM SAN MATTEO, THE 18TH DAY OF OCTOBER 1630.

Your most affectionate daughter,

S.M.Coloste

The little basket, which I sent you recently with several pastries, is not mine, and therefore I wish you to return it to me.

Suor Maria Celeste’s prescription for prayer and penitence in the face of the plague meshed perfectly with prevailing wisdom. Prayer surpassed or at least augmented the many available treatments, which included bloodletting, crystals of arsenic applied to the wrists and temples, small sacks of precious stones laid over the heart, and unguents made by cooking animal excrement together with mustard, crushed glass, turpentine, poison ivy, and an onion. The value of confession and penitence reached new heights during plague epidemics, for the disease, once it struck, left its victims no time to make amends.

The first symptom typically erupted as a swelling of the lymph nodes under the arms or between the thighs. These large, painful, pus-filled lumps, called buboes, gave the pestilence the name “bubonic plague.” Ranging in size from almonds to oranges, they were the focus of treatment by doctors, some of whom advocated burning the buboes with incandescent gold or iron, then covering the wound with cabbage leaves; others preferred to cut the buboes open with a razor, suck out the blood, and deposit three leeches on the site, topped by a quartered pigeon or a plucked rooster. Left alone, the buboes enlarged each day until they often burst on their own, provoking agony sufficient to rouse even the nearly dead to frenzy.

Since only a fraction of those who contracted the plague could hope to recover, the appearance of the bubo pronounced doom. Fevers rose high within hours of onset, accompanied by vomiting, diffuse pain that felt like burning or prickling, and delirium. Soon the skin displayed wheals and dark markings caused by subcutaneous hemorrhage. Death followed within the week, unless the disease also invaded the lungs, where it caused the coughing of a bloody, frothy sputum and killed the victim in two or three days flat—but not before it facilitated numerous new infections via droplets borne on the wind to be inhaled by the unsuspecting.

The plague leaped like fire from the sick to the whole. Even the discarded clothes or other belongings of the afflicted could communicate the disease. When one family member fell sick, the rest typically followed, and soon all were buried in the fields, as the laws of Florence barred plague corpses from the churchyards.

The Italian people recognized the plague as an ancient enemy, periodically banished but never vanquished. In its worst visitation, from 1346 through 1349, it claimed 25 million lives, or roughly one-third of the population of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.

“Oh, happy posterity,” exclaimed poet Francesco Petrarca when that Black Death robbed him of his beloved Laura, “who will not experience such abysmal woe and will look upon our testimony as a fable.”

Following the pandemic of the fourteenth century, the plague returned to one region or another at its own whim every few years, as though to remind the wayward of the tortures of Hell.

By the early seventeenth century, Europeans had gained enough experience with the pestilence to recognize the accumulation of dead rats in streets and houses as the harbinger of disease. The causal connection, however, remained elusive. People continued to blame the plague on miasmas of swampy air, the full Moon, conjunctions of the planets, famine, fate, beggars, prostitutes, or Jews. Two hundred years before the germ theory of disease, no one realized that the plague was caused by microbes living in and on the ubiquitous black rats.

*

When a sick rat died, its hungry fleas jumped the few inches to another animal, or to a nearby human. Having ingested infected blood, the fleas delivered the disease by inoculation with their next bite. The poisonous plague bacterium multiplied rapidly in a new host’s bloodstream until infection pervaded the body, attacking vital organs to cause kidney failure, heart failure, hemorrhaging blood vessels, and death by septic shock. (Galileo’s early description of the flea he observed through his microscope as “quite horrible” referred only to its ugliness, and not its true menace, for he had no inkling of the creature’s role in plague transmission.)

While live rats traveled with impunity on foot and aboard ship, exporting the plague hither and yon, people were confined to their houses by fear and municipal prohibitions. The Venetian doge imposed the first official quarantine in 1348, after the city death rate from plague had risen to six hundred per day. The doge’s council, seeking to isolate returning voyagers from the Orient, had decided on the duration of forty days—

quaranta giorni

in Italian, from which the word

quarantine

is derived—by selecting the same period of time that Christ had sequestered himself in the wilderness.