Getting Into Character: Seven Secrets a Novelist Can Learn From Actors (3 page)

Read Getting Into Character: Seven Secrets a Novelist Can Learn From Actors Online

Authors: Brandilyn Collins

Tags: #Writing

If the definition of the “Actor’s Technique” (found at the beginning of each chapter) sounds foreign, don’t worry. Remember, these definitions refer to the art of Method Acting, unfamiliar to most novelists. The “Novelist’s Adaptation” and subsequent explanation will make it clear. At the end of each chapter I’ve included sample passages, one from classic literature and one from my own work. I urge you to read these excerpts carefully, along with the questions and answers in the “Exploration Points.” The classic novelists didn’t have these “Secrets” to guide their work, of course, but in their own way they managed to produce the result. I include my own work to show you how I have used these Secrets. I certainly don’t want to give you the impression you should write like I do. You have your own writer’s voice. My goal is to show my use of each Secret in order to help you discover how to use it in your own voice .

By the time you finish this book, you’ll have covered an abundance of exercises and steps for the various secrets. And you might be tempted to think that with all the steps required to write just one scene, you’ll never get anything written! Not so.

Absolutely not

. The last thing I’d want to do is freeze up your writing.

I’ve dissected, listed, and labeled every element in these concepts so you can best understand them. But the good news is that the more familiar you become with these Secrets, the easier they will be to use, requiring far less conscious, step-by-step precision on your part. It’s like learning how to drive. When you first get behind a wheel, you have to pay attention to every detail. Hands at clock position ten and two. Watch for other cars. Turn on the blinker before changing lanes. But after a while, these things become second nature, and you don’t even think about them. Still, sometimes in bad weather—in ice or hard rain—you’ll need to return to the conscious effort of driving safely. In the same way, as you learn these concepts, they will become second nature. You’ll have to concentrate on their individual steps only when you run into a troublesome scene.

Enough introduction already. On with the Secrets!

SECRET #1

Personalizing

ACTOR’S TECHNIQUE:

As no two human beings are exactly alike, so every role is unique—a distinctive soul to be created. Attributing mere general mannerisms to characters based on their age and social class will produce “cutout dolls” that may just as well be moved from play to play. Through discovering the inner character and from observing real life—how one person holds his head, how another walks or uses her hands—the actor must pull together a composite of mannerisms that creates the unique character being portrayed.

NOVELIST’S ADAPTATION:

The technique of Personalizing each character is just as important in writing fiction as in acting. Without Personalizing, we face the pitfalls of clichéd characters such as the “crotchety old man” or the “ditsy blonde.” Our adaptation of Personalizing focuses not on hair color and body type, but on the discovery of a character’s

inner values

, which give rise to unique traits and mannerisms that will become an integral part of the story.

The Importance Of Personalizing

“You can dress him up, but you can’t take him out.” “All dressed up and no place to go.”

Ever heard those phrases? Their meanings share a common thread. Both imply that outer accoutrements are less important than inner character and motivation.

Personalizing is absolutely critical for a novel. Yet many writers, especially new ones, have particular trouble with the concept of developing full-fledged characters. As noted in the Novelist’s Adaptation, Personalizing focuses not on physical attributes but rather on a character’s inner values, which lead to traits and mannerisms. When I speak of “traits,” I mean the general attitudes of your character, such as patience, arrogance, humility, selfishness. Traits define the basic personality of your character, just as we use traits to define people in real life. When I speak of “mannerisms,” I mean specific movements of a character: the way he holds his head, the way she walks or talks, his facial expressions, etc.

But how do we go about Personalizing? And what can we learn from Method actors?

The Method actor’s secret to Personalizing is based on this principle:

Personalized characters are created

from the inside out.

In

Building a Character

, Stanislavsky notes that the most talented actors don’t just assign traits and mannerisms to a character based on general facts about the person. Instead, these actors allow traits and mannerisms to grow of their own accord by first discovering the character’s “right inner values.” These inner values are the core truths of the character. They define the person’s worldview. They drive his or her desires and actions.

For most novelists, Stanislavsky’s approach is a radical idea. Instead of allowing ourselves to discover our characters’ inner values, we tend to characterize them on the outside—merely dressing the mannequin, so to speak—hoping somewhere along the way to discover a few inner truths about them. But too often, we don’t go deep enough. The result? What’s often called “cardboard characters.”

The trouble is, no matter how exciting our plot, how intriguing the action, or how great the danger, readers will fail to be caught up in the story unless they connect on a deep level with your characters—especially the protagonist.

Years ago while I was walking the dock at a lakeside resort, a mental image of a character popped into my head. He was a young boy of about ten, a runaway, hungry and very alone. I envisioned him standing on the dock, head tilted back, watching a small group of people on a huge boat preparing to go out on the water. The longing this boy felt overwhelmed me. More than anything in the world, more than money in his pocket or food in his stomach, he wanted to be on the boat with those people. Only a few feet separated him from that boat, yet the distance may as well have been a canyon. He wanted to be up there not because they represented wealth, but because he simply wanted to

belong

. He yearned for that with all his might. So close to people laughing and enjoying each other, yet so very far. So utterly alone.

That little boy caught my heart. I knew I’d use him some day in a novel. He stayed in my head for a number of years until he morphed into a young woman, Paige Williams—the protagonist of

Violet Dawn

(book 1 in the Kanner Lake Series

).

I didn’t know any of Paige’s outward mannerisms or personality traits as I began to build that story. I knew something far more important—an inner value that shaped her: “Belonging is more important to me than anything else in the world.”

It’s not often that a character pops into my head like that, and I build a story around him or her. Usually I think of a basic plot and then discover my characters. But whether you start with a character or a plot in mind, ultimately it’s the characters and the choices they make that should drive your story. And where do our choices come from, especially in times of stress? Our inner values. What’s most important to us.

By the way, if you happen to envision exactly what a character looks like right away, that’s okay. If the character stands five feet four inches tall with brown hair and green eyes—great. But these outward characteristics don’t define

who she is

. You’ll still need to take the character through the Personalizing process to discover her inner values.

So how does this process work?

The Personalizing Process

Naturally, you’ll have to begin with the basic facts about your character. You probably have some idea as to who he or she is. However little or much you know is okay. It’s a start to learn more.

One of the ways authors learn more about their characters is to “interview” them. You may use a long list of questions regarding age, gender, likes, dislikes, background, education, family relationships, etc. That’s fine. Making a checklist of details is a good entry into the Personalizing process and will dovetail with what we’re trying to accomplish.

Other authors use a free-form method to get to know their characters, making notes as facts about them come to mind. Still other authors use techniques somewhere between the free-form and the structured interview. Whatever your method, you do need to discover the highlights of your character’s background and experiences, for these will color the person’s view of the world. But for true Personalizing, you have to dig a lot deeper. These facts will serve as only the beginning. Remember, your goal is to find your character’s inner values—the core truths in your character’s soul that drive him or her.

In a nutshell, here are the steps to Personalizing. We’ll go through each one to fully explain the process.

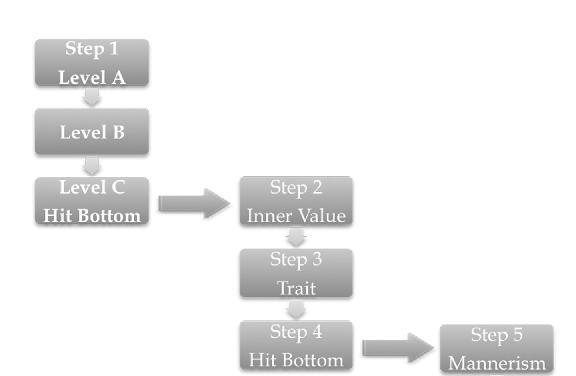

1.

Begin a line of questioning with your character and pursue it until you

“hit bottom.”

Hitting bottom means you arrive at the “So what?”—or logical conclusion—of that line of questioning.

2.

The final “So what?” question will reveal a core truth or

“inner value”

about your character.

3.

In turn, this inner value will lead to a

trait

.

4.

Then pursue this line of questioning even further to see if you can

hit bottom

a second time.

5.

If you can hit bottom again, you will discover a specific

mannerism

based on the inner value.

So how do you start this questioning process?

If Stanislavsky were alive today and willing to teach us novelists, his questioning process would most likely be based on the three levels of characterization that he describes in

Building a Character

. At each of these levels a deeper probing of the character gives rise to more personalized traits, which in turn reveal specific mannerisms. Stanislavsky’s disappointment lay in the fact that, amazingly, many actors stopped at Level A, and many others made it only to B. Yet only at Level C is true individualization reached.

All too often, novelists, like actors, tend to stop at Level B. We have understandable reason for doing so. Levels A and B aren’t very hard. We have one or two main characters in mind and a story to go with them, or perhaps we start with a story and figure out a couple of characters. Within the process of discovering our stories, we tend naturally to reach Level B. And then we think we have enough. But if you fail to reach Level C, you’ll miss discovering those valuable core truths about your character.