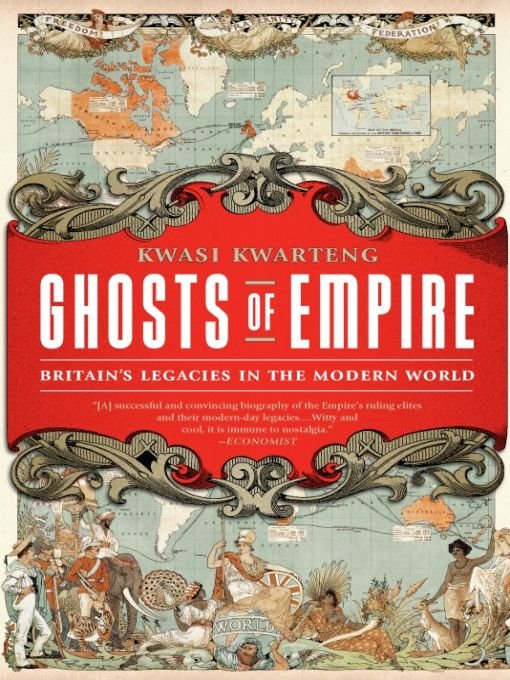

Ghosts of Empire

Authors: Kwasi Kwarteng

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Liber dicatur hic parentibus meis

amore grati filii piissimo

amore grati filii piissimo

Â

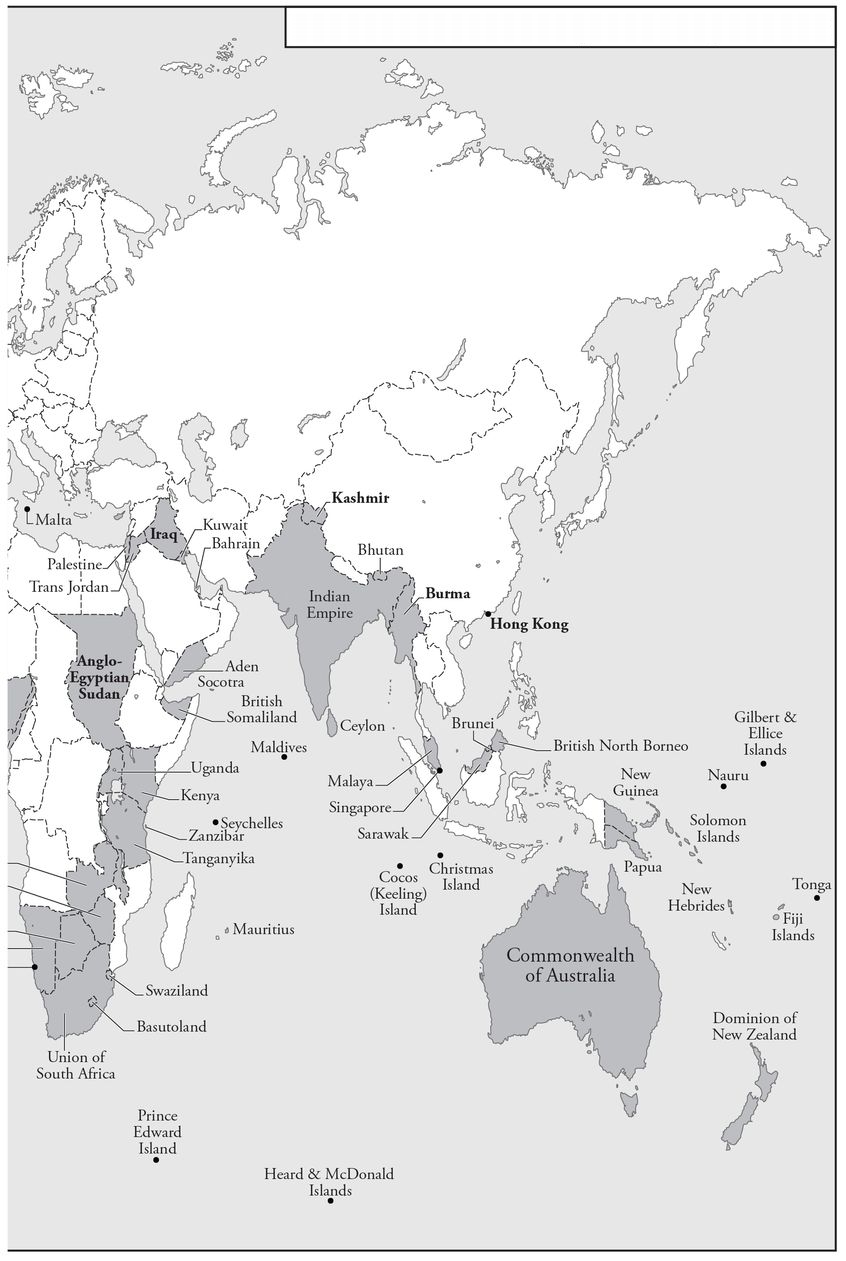

The extent of the British Empire at its height,

c

. 1925

c

. 1925

Introduction to the US Edition

To many Americans, the British Empire must seem remote and obscure. Yet no nation faced such similar problems to modern America as Britain at the height of its imperial glory. The British Empire, like the modern United States, was the world's pre-eminent superpower. It held sway over a large portion of the global population; for decades, Britain was the financial and commercial centre of the world. One American writer, Walter Russell Mead, has correctly identified the fact that the âtwo most recent great powers in world history were what Europeans still sometimes refer to as “Anglo-Saxon” powers.' In Mead's words, the âBritish Empire was, and the United States is, concerned not just with the balance of power in one particular corner of the world but with the evolution of what we today call “world order”'

1

.

1

.

The notion of âworld order', of course, is problematic and can be defined in various ways. Yet what can be asserted is that both the modern United States and the British Empire sought to project their power across the whole world. Anyone who wishes to understand the nature of American power today will profitably find parallels and similarities with Britain's own experience. As a consequence of interest in world order, the focus of this book is on the colonial empire, not the white dominions. Much of the debate about the British Empire in the first decade of the twenty-first century has really been a kind of proxy debate about the role of the United States. Recently, some historians and political scientists have openly suggested that the United States should follow Britain and try to impose its own âPax Americana' on the more anarchic parts of the planet. The model the United States is being asked to follow is one of administration and military occupation. Even the most strident neo-conservatives, the historians who say that empire is more necessary in the twenty-first century than ever before, have never suggested that millions of Americans should emigrate to places like Iraq on a permanent basis and establish their families there.

2

Such a programme follows the pattern set by Britain in the administration of its colonial empire,

and not the example of the âwhite dominions' whereby large numbers of British settlers developed broadly democratic systems of self-government. Aggressive modern imperialists do believe that an empire can keep the world safe and better administered; imperialism is sometimes offered as an answer to the problem of maintaining world order.

2

Such a programme follows the pattern set by Britain in the administration of its colonial empire,

and not the example of the âwhite dominions' whereby large numbers of British settlers developed broadly democratic systems of self-government. Aggressive modern imperialists do believe that an empire can keep the world safe and better administered; imperialism is sometimes offered as an answer to the problem of maintaining world order.

I contend that the example of the British Empire shows the opposite: empires, through their lack of foresight and the wide discretion they give administrators, lead to instability and the development of chronic problems. In addition to this, the idea of creating an avowedly interventionist American empire now seems, especially after the defeat of the Republican party in the 2008 presidential election, as absurd as the notion of absolute monarchy seemed to Britons of the nineteenth century. It also misunderstands the nature of empire. Britain's empire was not liberal in the sense of being a plural, democratic society. The empire openly repudiated ideas of human equality and put power and responsibility into the hands of a chosen elite, drawn from a tiny proportion of the population in Britain. The British Empire was not merely undemocratic; it was anti-democratic. The United States, in comparison, despite its difficult history, openly proclaims itself to be democratic, plural and liberal. Its avowed values could not be further removed from those of the British Empire.

The colonial empire inevitably brings up the hoary issue of race. People inevitably ask, âhow racist was the British Empire?' Clearly, it is difficult to answer this question satisfactorily, because issues of race and its treatment differed widely across the expanse of the empire both in terms of time and space. My contention is that in terms of administration itself, while there was clearly a great deal of racial arrogance among the administrative class as a whole, notions of class and hierarchy were as important, if not more so. In this respect I am happy to follow the work of David Cannadine, whose

Ornamentalism

(2001) put class very much to the foreground of analysis of Britain's empire. Cannadine argued that Britons during the empire saw themselves as âbelonging to an unequal society characterized by a seamless web of layered gradations . . . hallowed by time and precedent'.

3

Ornamentalism

(2001) put class very much to the foreground of analysis of Britain's empire. Cannadine argued that Britons during the empire saw themselves as âbelonging to an unequal society characterized by a seamless web of layered gradations . . . hallowed by time and precedent'.

3

In this book, I have tried to show what the British Empire was really like from the perspective of the rulers, the administrators who made it possible. As one recent historian has said, the task is to recover the âworld-view and social presuppositions of those who dominated and ruled the empire'.

4

This

does not mean that the âvictims and critics' were unimportant, but it does mean that any understanding of the empire should start with trying to capture the mentality of those who bore responsibility for an empire that was the largest the world has yet seen.

Ghosts of Empire

may be described as a post-racial account of empire, in so far as it does not regard the fact that the administrators were white, while the subject people were from other races, as the key determinant in understanding empire. Indeed, if one were to consider Ireland in its role as a subject nation under British rule in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, notions of race, in the narrow sense of skin colour, would simply not apply. Yet, the imperial arrogance, the high degree of status-consciousness and the self-assuredness of the administrative class would still be distinctive features of British rule. There is clearly more to understanding the British Empire than racial politics, important though this was.

4

This

does not mean that the âvictims and critics' were unimportant, but it does mean that any understanding of the empire should start with trying to capture the mentality of those who bore responsibility for an empire that was the largest the world has yet seen.

Ghosts of Empire

may be described as a post-racial account of empire, in so far as it does not regard the fact that the administrators were white, while the subject people were from other races, as the key determinant in understanding empire. Indeed, if one were to consider Ireland in its role as a subject nation under British rule in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, notions of race, in the narrow sense of skin colour, would simply not apply. Yet, the imperial arrogance, the high degree of status-consciousness and the self-assuredness of the administrative class would still be distinctive features of British rule. There is clearly more to understanding the British Empire than racial politics, important though this was.

Ghosts of Empire

is an unusual book about the British Empire in other ways: it examines aspects of Britain's legacy in parts of the world that are diverse in terms of geography and culture. The countries or territories that form the subjects of this book are, in many ways, still influenced by their connection with Britain. Many of these areas, like Iraq and Kashmir, have been prominent in the international press for some years; others, like Nigeria and Sudan, have been less widely written about, but all the countries, in my view, reveal certain similar characteristics of British rule.

is an unusual book about the British Empire in other ways: it examines aspects of Britain's legacy in parts of the world that are diverse in terms of geography and culture. The countries or territories that form the subjects of this book are, in many ways, still influenced by their connection with Britain. Many of these areas, like Iraq and Kashmir, have been prominent in the international press for some years; others, like Nigeria and Sudan, have been less widely written about, but all the countries, in my view, reveal certain similar characteristics of British rule.

The choice of Hong Kong was the easiest, since the departure of the British from Hong Kong in 1997, watched by millions of people on television, has been understood to be a symbol of the formal end of the British Empire. More relevantly, to readers in the twenty-first century, Hong Kong's destiny is now bound up with that of China, the most rapidly emerging super-power of the new century. Iraq's history as a dependent territory of empire was strictly a twentieth-century affair. Handed over to Britain in 1920, after the First World War, Iraq remained under formal British rule for only twelve years. Yet, for the next twenty-five years, Iraq was ruled by a monarchy that affected British manners and style. In Kashmir, a Hindu family was established to rule over an overwhelmingly Muslim kingdom. The Dogras ruled Kashmir for a hundred years. Yet Burma, which, like Kashmir, formed part of the jurisdiction of the Secretary of State for India, was treated in a completely different way from Kashmir. In Burma, an

ancient monarchy was toppled and replaced by direct British rule. The contrasting treatments of Kashmir and Burma, both of which were part of the Indian Empire, reveal the many inconsistencies of imperial policy. On the continent of Africa, within the boundaries of both Nigeria and Sudan, there existed ethnic and racial animosities that were only exacerbated by imperial rule. These animosities have haunted the post-imperial destinies of both countries.

ancient monarchy was toppled and replaced by direct British rule. The contrasting treatments of Kashmir and Burma, both of which were part of the Indian Empire, reveal the many inconsistencies of imperial policy. On the continent of Africa, within the boundaries of both Nigeria and Sudan, there existed ethnic and racial animosities that were only exacerbated by imperial rule. These animosities have haunted the post-imperial destinies of both countries.

The British Empire has always been with me. My parents were born in what was then called the Gold Coast in the 1940s and had experienced the empire firsthand. My father entered secondary school in January 1956, less than fifteen months before the Gold Coast became independent as Ghana in March 1957. My father's secondary school was designed on traditional Anglican lines, and although the school had been founded in 1910, it imitated more traditional, older English establishments. The headmaster of the school was an Englishman, of a type familiar in the colonies; he was a product of Winchester, England's oldest boarding, or âpublic', school and Cambridge University.

Other books

In the Company of Witches by Joey W. Hill

El camino de Steve Jobs by Jay Elliot

Gayle Eden by Illara's Champion

Lullabye (Rockstar #6) by Anne Mercier

The Sparrow (The Returned) by Jason Mott

The Next Little Thing (Jackson Falls #4) by Laurie Breton

Malice in London by Graham Thomas

Afterburn by Sylvia Day

Californium by R. Dean Johnson

Chasing Daybreak (Dark of Night Book 1) by Ranae Glass