Going Back

GOING BACK

Gary McKay served in Viet Nam as a platoon commander and has been back to Viet Nam four times in the past ten years. He has written several books on the war, including

In Good Company

;

Delta Four

;

Bullets, Beans & Bandages

;

On Patrol

with the SAS

;

All Guts and No Glory

(with Bob Buick);

Jungle

Tracks

(with Graeme Nicholas); and

Viet Nam Shots

(with Elizabeth Stewart). He is a full-time non-fiction writer and freelance historian.

GARY McKAY

GOING BACK

Australian veterans return to Viet Nam

First published in 2007

Copyright © Gary McKay 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The

Australian Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web:

www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Going back : Australian veterans return to Viet Nam.

Bibliography.

Includes index.

ISBN 978 1 74114 634 9 (pbk.)

1. Vietnam War, 1961â1975 â Veterans â Australia. 2.

Veterans â Travel â Vietnam. 3. Vietnam War, 1961â1975 â

Personal narratives, Australian. 4. Vietnam â Description

and travel. I. Title.

959.7043394

Set in 11.5/15 pt Requiem by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Printed in Australia by McPherson's Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

3 Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) and surrounds

Part III: Making peace with the past

Appendix: Post traumatic stress disorder

Going back, gaining closure

Dare it be written that never, in the field of bringing closure to the personal equation of human conflict, has so much been done for so many by just one: namely Gary McKay as author of this book. With apologies to Winston Churchill, I have amended his famous Battle of Britain declaration to salute a most vital effect of this book, which provides many examples of the bittersweet experience of veterans returning to the very ground where they lost their legs or their mates or both.

The Viet Nam War was, in many ways, a young person's war on all sides, in part because the National Service call-up in Australia reduced the average age of soldiers in combat to around twenty-one. In turn this has meant these veterans, post the Viet Nam War, have some fifty years or more to live, and so a long time to dwell on their memories of Viet Nam and all the agonies encountered there.

Matching this in recent times is a huge upswing in the affordability of overseas travel: as Viet Nam opened up its tourist industry many veterans became curious to return and, after a taste of modern Viet Nam and after overcoming any personal demons, they have kept on returning.

However, not all have had the time, desire or wherewithal to visit; for those veterans, this book offers the next best thing: a set of epic accounts of veterans âgoing back' to read and be enriched by. Equally, those about to go back can prepare a whole lot better for that return visit by absorbing the good, the bad and the ugly that may be encountered.

Above all else, this book will help many to gain an enhanced sense of closure, something that was never going to be easy given the way the war ended for the allies. The defeat was not so much at the hands of the North Vietnamese but at the hands of the Pentagon and various US Defense Secretaries and other strategists, who made big mistakes and allowed the war to continue even after they had recognised they were on the wrong track.

As Gary McKay writes, no Australian who served in Viet Nam has anything to be ashamed of, but the losses remain a big cross to bear, including those veterans who made it safely back but then died prematurely due to post traumatic stress disorder and other ills.

The Vietnamese also sustained huge losses in this curious war and will write the war their way. But bit by bit the rhetoric moves towards the immortal words of Kemal Atatürk, then addressed to the mothers of Anzac soldiers, embracing and saluting their contribution at Gallipoli: âAfter having lost their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well.'

Gaining closure will be greatly helped by this book, a long overdue and necessary postscript to the Viet Nam War (or American War or, more accurately, the Pentagon War).

Tim Fischer

Ex 1 RAR and former Deputy Prime Minister

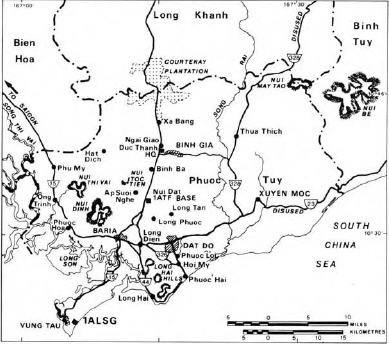

Phuoc Tuy Province (c. 1965â75)

As a young man I served in South Viet Nam in 1971 as a rifle platoon commander with the 4th Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment (4 RAR). In 1993 I made my first trip back to Viet Nam because I was writing a book that was partly funded by a John Treloar Research Grant from the Australian War Memorial. I wanted to return to where I had served, fought and nearly died after being severely wounded. I saw very little of Viet Nam when I was first there at 23 years of age. All I had briefly seen was the port of Vung Tau, the 1st Australian Task Force (1 ATF) base of Nui Dat, and a very large number of trees and bushes as I patrolled through the tropical jungles of Phuoc Tuy Province.

Indeed, the first time I saw Tan Son Nhut airport in Ho Chi Minh City was in late 1993, when 23 former members of Delta Company, 4 RAR, and a few ex-soldiers from 3 RAR and a sprinkling of wives landed for a three-week visit. It was stinking hot, extremely humid and had the rotting-vegetable smell of the tropicsâjust as the town of Vung Tau had smelt when I went there on a rest and convalescence (R&C) break two decades before. Many other memories came flooding back almost straightaway, and I was constantly bombarded by flashbacks and recall of times good and bad, funny and sad.

I have since been back another five times, and always on a research trip of some description. With each new visit I have expanded my trips and taken in more of that beautiful country. In 2002 my 21-year-old daughter Kelly joined me on one such sojourn. She also fell in love with Viet Nam.

I realised that as Viet Nam veterans are approaching retirement and their kids are off their hands and their responsibilities have waned, many are now taking to the highways as âgrey nomads' and discovering Australia's beauty, or are taking off overseas. The number that are returning to Viet Nam for holidays and pilgrimages is growing, and I wanted to write this book to help other veterans decide whether to revisit the land where they served our nation in conflict, or whether perhaps to stay at home and buy the Winnebago instead.

To document the memories of those who have already made the journey back to Viet Nam, I gathered first-hand accounts from the men and their partners through interviews and letters, and I am indebted to them for allowing me to intrude into their private thoughts and recollections in compiling this book. I strongly suggest that those contemplating returning to their old battlefields grab a copy of my book

Australia's Battlefields in Viet Nam

for guidance; it also contains some suggested itineraries for those wanting to visit the Task Force area of operations. I also recommend that travellers obtain a copy of the latest edition of the Lonely Planet guide to Vietnam; it is well worth the money and has some very useful tips.

At times in this book I have used the term âthe American War'. The Second Indochina War (or Viet Nam War, as the west referred to it) began after the Viet Nam Communist Party decided early in 1959 to sanction greater reliance on military activity and to start infiltrating South Viet Nam. Inside Viet Nam this war became known as the American War.

I am indebted to my publisher Ian Bowring of Allen & Unwin for allowing this little book to proceed. It is a niche book, but as befits Australia's Publisher of The Year for at least seven years, they do publish âbooks that matter'. My thanks also go to my editors Clara Finlay and Katri Hilden, and to the 5 RAR tour group of 2005 who allowed me to accompany them to Viet Nam as a case study for this book. Their assistance, forgiveness and friendship are truly appreciated.

For many veterans returning to Viet Nam, the visit will partly be a pilgrimageâa trip that will see them return to a place where normality was subsumed by abnormality, and where killing fellow human beings was tragically taken as the norm. A co-author of mine, Elizabeth Stewart, a historian at the Australian War Memorial, wrote a paper on pilgrimages and I am indebted to her for allowing me to quote extensively from her very well researched work. On the subject of pilgrimages she wrote:

Pilgrimage: the Macquarie Dictionary definition describes it as a journey, especially a long one, made to some sacred place as an act of devotion. In the past, pilgrimage has been most often associated with religious customs and travel. Today, though, pilgrimage is increasingly associated with secular events. Think of the crowds that flock to Gracelands on the anniversary of the death of Elvis Presley, of the survivors and relatives and friends of those who died in the Bali bombings who congregate on Kuta Beach every year, and of course, the thousands of people who make the journey to Anzac Cove in Turkey every Anzac Day. Although many of the ceremonies held at these places have some religious content, they are largely held to commemorate loss and offer a chance for public bereavement.

1