Goodbye, Darkness (12 page)

Before the invasion, the Nipponese needed to sever Australia's supply lines to the United States and build a staging area. To achieve the first, they were building airfields in the Solomon Islands. The staging area would be New Guinea's Port Moresby, three hundred miles from the Australian coast. The Battle of the Coral Sea — actually fought on the Solomon Sea — had turned back a Jap fleet which had been ordered to capture Moresby by sea. Then the Japs seized a beachhead at Milne Bay, halfway to their objective. MacArthur pored over maps and decided that Moresby would be the key to the campaign. He said: “Australia will be defended in New Guinea,” and: “We must attack! Attack! Attack!”

But where? In the tangled, uncharted equatorial terrain, the two suffering armies could only grope blindly toward each other. Some offshore isles were literally uninhabitable — U.S. engineers sent to survey the Santa Cruz group were virtually wiped out by cerebral malaria — and subsequent battles were fought under fantastic conditions. One island was rocked by earthquakes. Volcanic steam hissed through the rocks of another. On a third, bulldozers vanished in spongy, bottomless swamps. Sometimes the weather was worse than the enemy: at Cape Gloucester sixteen inches of rain fell in a single day. And sea engagements were broken off because neither the Japanese nor the American admirals knew where the bottom was.

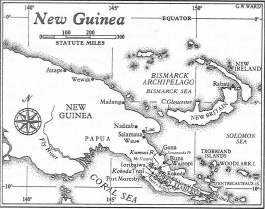

The Allies were slow to comprehend the Solomons threat, but by the late spring of 1942 they had brought New Guinea into full focus. The world's second largest island (second to Greenland), New Guinea stretches across the waters north of the Australian continent like a huge, fifteen-hundred-mile-long buzzard. As you face the map, the head is toward the left, southeast of the Philippines. The tail, to the right — at about the same degree of latitude as Guadalcanal in the Solomons — is the Papuan Peninsula. Both armies had come to realize that whoever held this peninsula would command the northern approaches to Australia. In taking Milne Bay the enemy had nipped the tip of the tail. That troubled MacArthur, but didn't alarm him; he could count on the Australians to dislodge them; the threat wasn't immediate. Meanwhile, however, another Jap force had anchored off Buna and Gona, villages on Papua's upper, or northern, side. Their purpose was obscure. Between Buna and Gona on the north and Port Moresby on the south loomed Papua's blunt, razor-backed Owen Stanley Range, the Rockies of the Pacific, rising tier on limestone tier, its caps carrying snow almost to the equator and its lower ridges so densely forested that some spurs resembled paintings by Piero della Francesca. To send an army over these forbidding mountains, upon which more than three hundred inches of rain falls each year, was regarded as absolutely impossible. MacArthur sent two of his ablest officers to Moresby, directing them to study its defenses. They came back full of assurances. The city was surrounded by water and impenetrable rainforest, they said. They omitted one detail. Either because they hadn't seen it or because they regarded it as insignificant, they failed to mention a little track that meandered off into the bush in the general direction of the Owen Stanleys. Soon the world would know that winding path as the Kokoda Trail.

Anyone trying to grasp the nature of the fighting which now lay ahead must first come to grips with its appalling battlefields and the immensity of the Pacific Ocean. The first task is difficult, the second almost impossible. It is a striking fact that you could drop the entire landmass of the earth into the Pacific and still leave a vast sea shroud to roll, in Melville's words, “as it rolled five thousand years ago.” Geographers usually divide Oceania into three parts — Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia — but these terms are confusing and largely irrelevant to the campaigns of World War II. The foci of action in 1942 were New Guinea, the Solomons to the east, and, between them, the Bismarck Archipelago, whose two chief islands, New Britain and New Ireland, resemble the letter

J

inverted and on its back, with New Britain as the shank and New Ireland as the hook. In the Allied grand strategy, the Pacific would ultimately be divided into two theaters of war. On the left, MacArthur would drive north through New Guinea to the Philippines. Meanwhile Chester Nimitz and his fellow admirals, having stopped the Japs in the Solomons, would lunge across the central Pacific, hopping over a chain of islands: Tarawa, the Marianas, Iwo Jima, to Okinawa. At that point the twin offensives would merge. Okinawa would be the base for an American invasion of the Japanese home islands, with Nimitz commanding the fleet and MacArthur sending the GIs and Marines ashore. None of this, however, was envisaged in that first desperate year of the war. The geography must be mastered first.

Names on maps of the southwest Pacific, where the first battles were fought in 1942, are deceptively familiar, for most of them are those of Western explorers, European statesmen, and their European homelands, such as the Owen Stanleys (for an English voyager of the 1840s); the Shortland Islands (after John Shortland, a sixteenth-century British sailor); Bougainville (for Louis Antoine de Bougainville, a Frenchman after whom the bougainvillea creeper was also named); Finschhafen and the Bismarcks (German); and, more obviously, New Georgia, Hollandia, and New Hanover. New Guinea was christened by a Spaniard, Ortiz de Retes, and Papua — originally “Ilhas de Papuas” — by a Portuguese, Antonio de Abreu. Now and then a native name, like Kapingamarangi, Mangareva, or the Solomon isle of Kolombangara, suggests the primitive force in the greenery, in the dazzling glare of liquid sunshine that conceals a shimmering Senegalese blackness which, in turn, in its very quiddity, gleams with an ultraviolet throb. Conrad, writing of Africa, put it well. It is the heart of darkness, the lividity at the core of the most magnetic light.

In the view of World War II GIs and Marines, most of what they had heard about the South Seas was applesauce. They had expected an exotic world where hustlers like Sadie Thompson seduced missionaries, and Mother Goddam strutted through

The Shanghai Gesture

, and wild men pranced on Borneo, and Lawrence Tibbett bellowed “On the Road to Mandalay” while sahibs wearing battered topees and stengah-shifters sipped shandies or gin pahits, and lovely native girls dived for pearls wearing fitted sarongs, like Dorothy Lamour. Actually, such paradises existed. They always have. Tahiti, forty-six hundred miles east of New Guinea, is one of them. In 1777 Captain Cook's surgeon's mate wrote of seeing there “great number of Girls … who in Symmetry&proportion might dispute the palm with any women under the Sun.” Another visitor noted the plays enacted by Tahiti's

arioi

sect, in which “the intimacies between the sexes were carried to great lengths.” These dreamy islands could have been matched elsewhere in 1942. What young Americans in the early 1940s could not understand was that the local cultures, delicate and ephemeral, could not coexist with engines of death and destruction. GIs put down natives as “gooks.” To the Diggers they were “fuzzy-wuzzies.” White men who live among them, or have traveled widely in the islands, call them “indigenes,” or sometimes “blackfellows,” names of simple dignity to which they are surely entitled. It is true that theirs was, and for the most part still is, a Stone Age culture. The first wheel many of them saw was attached to the bottom of an airplane. It is equally true that their simple humanity would prevent them from even contemplating a Pearl Harbor, an Auschwitz, or a Hiroshima, and that their devotion to wounded Australians during the war won them the altered name of “fuzzy-wuzzy angels.”

Before the war, before the great colonial empires began to come unstuck, indigenes were ruled by lordly Europeans who called themselves Residents and lived in enormous Residencies. Some of these buildings survive. In central Java, for example, you can find the ruins of what was once a Dutch Resident's Residency, a huge bungalow on the brow of a hill with a high thatched roof supported by Doric and Corinthian pillars, so as to form a broad veranda. Once the householder answered to the name of “Tuan.” Today, in his abandoned, walled-in, wildly overgrown garden are areca palms, fruit trees, and roses, a blowsy tribute to one man's faith in white supremacy.

It was a mighty force in the floodtide of imperialism. Here, “Out East,” as the British put it, a European who would have been a clerk or a shopkeeper at home could become, because of the color of his skin, an absolute monarch. His native vassals — and he had swarms of them — were each paid four cents a day. He wore a pith helmet and immaculate white ducks, and dined well; in Sumatra's thirty-two-dish rice banquet, each successive dish bore a ball of rice topped by a different delicacy, among them fried bananas, grated coconut, duck, sausages, chicken, and eggs. If he was single, he hired a mistress by the week, and if he was permissive, he allowed her to use his private bidet. His sports were polo, golf, and tennis — in Singapore alone there were six golf courses and two thousand tennis courts. On vacation he could visit “B.N.B.” (British North Borneo), “F.M.S.” (Federated Malay States, also a crown colony), Hanoi's opera house, which was large enough to seat every European who might want to come, or Saigon's famous theater, the most celebrated in the Far East, where a young entertainer named Noel Coward made his dramatic debut in

Journey's End

, a play which, had his audiences but known it, foreshadowed the end of their way of life. In Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, the French are not, of course, remembered with affection. Neither are the Dutch in the Malay Barrier. During World War II Sukarno was a Japanese puppet, and his seventy million fellow Indonesians thought none the less of him for it.

On the other hand, New Guinea's indigenes have warm recollections of Caucasians and treat them with great respect. In 1942, even before the triumphant Japanese had settled in, one black tribe from the interior crossed two hundred miles of hills and strand forest to join the thin line of Australians defending Moresby. Had the Japs been friendlier, they might have converted some of the Papuans. Instead, like the Nazis in the Ukraine, they alienated potential friends by barbaric policies. Islanders who failed to bow deeply to all Japanese were slapped in the face — a custom in the Nipponese army, but a mortal insult in New Guinea. Moslems' skullcaps were knocked off with rifle butts. Use of the English language, or even pidgin, was forbidden. Blackfellows had to carry ID cards and armbands signifying Nipponese ratings of their degrees of trustworthiness. The Japanese language and Greater East Asia propaganda were compulsory in schools. So ruthless were Hirohito's secret police in pulling out the fingernails of uncooperative natives that their jeering query, “Do you need a manicure?” triggered fear and resentment throughout Papua. The Japanese simply did not understand these people. They thought they could gain face by humiliating their European and American POWs. Nips carried a pamphlet written by one Colonel Masanobu Tsuji which told them: “When you encounter the enemy after landing, think of yourself as an avenger come at last face-to-face with his father's murderer. Here is the man whose death will lighten your heart of its burden of brooding anger. If you fail to destroy him utterly you can never rest in peace.” The consequence of this was a brutal treatment of prisoners beyond any laws of war — the 1957 film

Bridge on the River Kwai

was based upon a real incident — which aroused the compassion of the gentle natives around Port Moresby.

Americans seem to have a special place in native hearts. When the Japs had conquered Manila, General Homma ordered a victory parade, the music to be provided by a local band. An audience of natives was rounded up. The tunes were greeted with scattered applause until the last one, which triggered a standing ovation. Homma, startled, smiled in all directions. He didn't know the Filipino musicians were playing “Stars and Stripes Forever.”

So there are still parts of the black world where the white man is welcome. Nevertheless, anyone who wants to know the lay of the land in the islands needs a key friend, who has other friends, who have friends here and friends there — a cordial net of human relationships which makes all things possible. The first friend is the important one. Finding him in Papua New Guinea is not easy. The inhabitants speak 760 languages, not counting dialects. During my recent visit to Port Moresby a defendant and a string of interpreters had to go through seven languages to enter his plea; the horrified judge, foreseeing what this would mean in a trial, dismissed the prisoner. Often communication can be achieved only in bastardized pidgin. If a blackfellow wants to say “my country,” it will come out “kantri-bilong-mi” (country-belong-me). And he will be right; since 1975 Papua New Guinea has been an independent nation, though economically it is still a colony, with an Australian sitting beside virtually every key official, making recommendations which are almost always accepted.

My first friend of a friend in New Guinea is barrel-chested Sir John Guise, the independent country's first native governor-general, now retired and living in Moresby. He receives me in his modest four-room home of cinder block painted light green. The chairs are plastic; the floor, linoleum; the only appliances in sight are a stereo, a Banks radio, and a floor fan, all powered by batteries. This is the life-style of a man who presided over a nation as large as New England, the Middle Atlantic states, and West Virginia combined, populated by three million Papuans. Unless they are living in old European Residencies, the political leaders in the emerging nations of the southwest Pacific live more frugally than the mayor of a typical American city. Sir John waves me to a chair and takes one himself. He is chewing betel nut, which, if you are unaccustomed to it, is an unsettling experience for the spectator; every time the chewer opens his mouth his gums appear to be hemorrhaging. I first encountered it in India. The effect on the user is much like marijuana's. Under its influence, Sir John looks in my direction with what we in the Marine Corps called a thousand-yard stare; then the stare shortens until his eyes are locked into mine. He speaks of his people and their lands, and his voice is incredibly deep, like thunder rolling down the vault of heaven. His complexion is cordovan, skin rippling over knotted tendon and stretched muscle. The impression is of an immensely powerful paterfamilias; and as word of his visitor spreads through the neighborhood, his home, and then his chair, are in fact surrounded by indigenes, all of whom are related to him.