Goodbye, Darkness (31 page)

Les Braves Gens

A

mericans at home thought all the island battlefields in

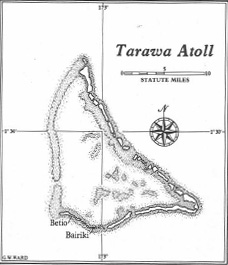

the Pacific were pretty much alike: jungly, rainy, with deep white beaches ringed by awnings of palm trees. That was true of New Guinea and the Solomons, but most of Admiral Nimitz's central Pacific offensive, which opened in the autumn of 1943, was fought over very different ground. Only the palms and the pandanus there evoke memories of the South Pacific, and the pandanus do not flourish because rain seldom falls. A typical central Pacific island, straddling the equator, is a small platform of coral, sparsely covered with sand and scrub bush, whose highest point rises no more than a few feet above the surf line. Tarawa (pronounced

TAR-uh-wuh

), like most of the land formations in this part of the world, is actually an atoll, a triangular group of thirty-eight islands circled by a forbidding coral reef and sheltering, within the triangle, a dreamy lagoon. The fighting was on one of Tarawa's isles, Betio (

BAY-she-oh

), because that was where the priceless Japanese airstrip was. Betio is less than half the size of Manhattan's Central Park. No part of it is more than three hundred yards from the water. A good golfer can drive a ball across it at almost any point.

Tarawa is in the Gilbert Islands. Nimitz's real objective was Kwajalein, in the Marshall Islands, over five hundred miles to the northwest. The largest atoll in the world, sixty-five miles long, Kwajalein would provide the Americans with an immense anchorage and a superb airdrome. But Tarawa and its sister atoll Makin (pronounced

MUG-rin

) had to fall first. Unlike the Marshalls, which had been mandated to Japan in the Treaty of Versailles, and which Hirohito's troops had spent twenty years arming to the teeth, the Gilberts, where Tarawa was, had been a British crown colony. The Nips had arrived there two days after Pearl Harbor. Colonel Vivien Fox-Strangeways, the resident British administrator, had fled Tarawa in a small launch, dashing from island to island by day and holing up in coves by night until a British ship picked him up in the Ellice Islands, to the south. Since then the only Allied contact with the Gilberts had been the ineffectual foray by Carlson's Raiders on Makin. Carlson reported that he hadn't encountered much resistance. By the autumn of 1943 that was no longer true. Carlson, ironically, had been the agent of change. Warned by his strike, the enemy had strengthened the defenses of the Gilberts, particularly those on Tarawa's Betio. The Japanese needed that airstrip there. It is a sign of their determination that they had chosen Betio's beach to site the British coastal defense guns they had captured at Singapore.

Before the war these islands had been as insignificant as Guadalcanal — remote, insular, far from the Pacific's trade routes. The islanders lived in thatched huts, harvested copra, fished for tuna, and watched the tides alter their shoreline from year to year. A schooner arrived once every three months to exchange tobacco and brightly colored cloth for copra. The Gilbertese were living over valuable phosphate deposits, but in the 1940s no one was aware of it. Indeed, few outsiders even knew or cared about the islands' existence. Christian missionaries were exceptions; by the time of Pearl Harbor half the natives were Catholics and the other half Protestants. They paid a price for their devotion when the Nips landed. Under threat of death Gilbertese men were forced to defecate on their crude altars; Gilbertese women had to perform obscene ceremonies with crucifixes. It was the same old story: islanders who had little stake in the war, and might have been befriended by their conquerors, were alienated by a barbarous occupation policy. Long before the fall of 1943 the Japs were thoroughly hated throughout the Gilberts.

In planning the seizure of Makin and Tarawa, Nimitz chose as his commander Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, who had performed superbly at Midway seventeen months earlier. Spruance divided his armada of over a hundred warships into three task forces, one for Makin, one for Tarawa, and one to throw up an umbrella of fighter planes from seventeen carriers, challenging Jap fliers from Kwajalein who tried to disrupt the two operations. In the event, enemy warplanes were intimidated. Hirohito's troops were not. Makin, which was supposed to be easy, wasn't. GIs didn't take it until the fourth day of fighting. Here, for the first but not the last time, a basic amphibious issue arose between U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps generals. Soldiers moved slowly to keep casualty lists short. Marines lunged at the enemy, sometimes at reckless speed, because they knew that until the fighting ended the fleet which had landed them would be vulnerable to enemy attack. They believed that Makin vindicated them. While GIs crawled ashore there, a Nip sub torpedoed an American carrier, drowning ten times the number of men who died fighting on Makin.

Tarawa was to be a tragedy for different reasons, which, seen through the telescope of hindsight, seem incomprehensible. Everyone knew that Tarawa — which is to say Betio — would be tough. The reef was formidable. The enemy had mined it. The beach bristled with huge guns, concrete obstacles, and barbed-wire concertinas designed to force invaders into the fire zone of cannon and machine guns. That was only part of the problem, but it was the part known to Spruance and his staff before the first wave of Marines went in. The greater problem was the reef. The only craft which could cross a jutting reef, even after the mines had been defused, were what we called “amphtracs” — amphibious tractors. Driven by propellers, they could move through water at four knots; their caterpillar tracks would carry them over land, including the reef ledge, at twenty miles per hour. Twenty Marines could ride in each amphtrac. The landing force needed all it could get. But there were few available, and Spruance's staff, notably Rear Admiral Turner, took a sanguine view of the tidal problem anyway. Using 1841 charters, they assured the Marines that at H-hour the reef would be covered by five feet of water, which meant that a loaded Higgins boat, drawing between three and four feet, could cross it. Therefore there would be enough amphtracs for the first wave, though, they conceded, there would be none for those following.

This defies understanding. A landing in spring would have been another matter, but Fox-Strangeways had described Betio's low, dodging autumn tides to the Americans. Major F. L. G. Holland, a New Zealander who had lived on Tarawa for fifteen years, said the tide might be as little as three feet. And the night before the Betio attack Rota Onorio, now Speaker of the Gilberts' House of Assembly and then a fourteen-year-old boy, paddled his dugout out to the Allied fleet and told naval officers that tomorrow the reef would be impassable, even at high tide. He, Fox-Strangeways, and Holland were ignored. Then, in the morning, the situation worsened when the fleet's timetable began to come apart. The transports carrying the Marines were trapped between Spruance's battleship bombardment and the replying fire from the enemy's shore guns. They moved, delaying the landing and missing the tide. Next it was discovered that the battleship captains and the carrier commanders had failed to consult one another; the ships' thirty-five-minute salvos ended to permit the carrier planes to come in, but the planes, whose pilots had been given another schedule, were a half hour late. That permitted the Jap batteries to open up on the transports, further delaying the landing waves. The air strike was supposed to last thirty minutes. It lasted seven. Finally, everyone awaited what was supposed to be the last touch in softening up the beach defenses, a massive B-24 raid from a base in the Ellice Islands. They waited. And waited. The B-24s never arrived. H-hour was delayed by forty-three more precious minutes.

After the battle Seabees built more than nineteen miles of roads on Tarawa and erected piers, observation towers, and radio towers; installed a fuel pipeline; and gave the islands electricity, refrigeration, mosquito control, water purification, and a twenty-four-hundred-foot mole. The atoll's Australian nuns were presented with new blue-and-white habits. Then the war ended and the Americans left. Most of the technological marvels were ruined by the weather. The Gilberts once more became backwaters. Today Tarawa is less lonely than it was before the war, but by the standards of the rest of the world it is still remote. The atoll may be reached by air twice a week from Nauru, itself obscure, or every other week from Fiji. I choose to come via Nauru Airways. Peering down from my lazy flight — we are over an hour late — I see the twenty-two-mile reef first, a lopsided horseshoe containing the beautiful pink isles, each with its umbrella of palms twisted by centuries of typhoons. Sturdy Seabee rock-and-coral causeways still connect some of the islands in the atoll, though not Betio, which since 1943 has been regarded as the pariah of the Gilberts. As we enter our glide pattern I look down on the shore, four thousand yards within the reef, and see the horizontal rippling of the sand where the sea has ridged it. Here and there on Betio, rusty hulks are visible, though there is no way of telling whether they are the remains of boats, tanks, or shore batteries. The waters are placid. The islets are like stones in a delicate necklace. The trees lean indolently. It seems inconceivable that what happened here happened here.

We land on Bairiki, the islet closest to Betio. The runway (“Bairiki International Airport”) is there. So are the government's offices; so is the atoll's tiny, whitewashed cinder-block Otintai Hotel. The airfield's tin-roofed, open-sided terminal building is about the size of a Beverly Hills carport. Outside are little rustlings and stirrings among the palms, as though they were whispering among themselves, but inside the terminal one's senses are assaulted by a shouting, sweating, colorfully dressed crowd. Sometimes, in a paranoid mood, I wonder whether these mobs at Pacific airports aren't always the same mob, a troupe that flies ahead of me to block my way. They all look the same, sound the same, smell the same. Abruptly the chaos thins and I am confronted by a black giant wearing Her Britannic Majesty's white tropical uniform — white short-sleeved blouse, white shorts, white pith helmet. He studies my passport, stamps it, rummages through my B-4 bag, and waves me on.

Outside I board a minibus. One by one, then two by two, other passengers join me, until the bus resembles one of those Barnum and Bailey circus cars packed with flesh, or the Marx Brothers' stateroom in

A Night at the Opera

. But I have a window. It provides an astonishing glimpse of one of those high, old-fashioned London taxis which were replaced by smaller, sleeker cabs years ago. The taxi bears Elizabeth II's coat of arms on its doors. Within, a pukka sahib — later I learn he is Governor the Honourable Reginald Wallace — is waving cheerily. No one waves back, or even glances in his direction. Thus, as in India, the British Raj ends with neither bang nor whimper but merely with massive indifference among its former, or soon-to-be former, subjects. In a few months, one of my fellow passengers tells me, the Gilbertese will become independent. He proudly shows me the new nation's flag: a yellow bird and sun on a red background, with wavy blue and white stripes below. It is vaguely suggestive of Arizona's state flag.

Here in the far reaches of the Pacific there is a kind of camaraderie among Europeans, a generic term which includes Americans, and within an hour I am lunching at the Otintai with four new acquaintances, all British, one of whom, a stocky woman who works for the World Health Organization, recently spent a week crossing the mountainous spine of Guadalcanal, a feat which has been matched by few, if any. My friends are all hearty, jolly, and blessed with that English love of incongruity which makes the eclipse of British power almost droll. A slender Welsh economist married to a Polynesian girl has discovered that one of the old Japanese blockhouses on Betio is precisely the size of a squash court; he is using it as such. Tony Charlwood, a chief master in the Royal Navy and an ordnance expert — his last assignment was defusing IRA bombs in Belfast — has just finished a three-month job here, removing from the beaches, at low tide, seventeen tons of live ammunition, including several eighteen-inch shells. He makes it sound like a parlor game.

The most interesting of the four is Ieuan Battan, deputy secretary to the Gilbertese chief minister, a handsome, husky man who just now has a grisly problem, though he speaks of it lightly. He has to handle the delicate consequences of finding the skeletons of fighting men, which are discovered from time to time when new sewer lines are laid, say, or when children are building sand castles around old spider holes. Last week a group of little boys unearthed the fleshless corpses of four Japanese and one American. How, I ask Ieuan, can he tell the four from the one? It is easy, he replies; the American was wearing dog tags and a Swiss watch, and Japanese femurs, teeth, and skulls are microscopically different from ours. At the moment it is the Nipponese skulls which are worrying him. A nine-teen-man delegation is on its way from Tokyo to cremate what is left of their countrymen. But the children who found the craniums are exhibiting them on their windowsills, and he must persuade the boys to relinquish them. If this is black humor, there is worse to come, though I suspect it may be fictive. One of my companions insists that recently two couples were making love on a sand dune known to be littered with old artillery duds. One couple, still in the prelims, heard the other man shout, “I'm coming!” The girl cried, “I'm close!” Then they blew up.