Goodbye, Darkness (27 page)

The Ilu sandspit, 1978

Fully alerted now, the Second Battalion of the First Marines, entrenched on the west bank of the Ilu, turned Japanese rice bags into sandbags and strengthened their line with barbed wire taken from the Lever Brothers plantation. A battalion of the Eleventh Marines arrived with 75-millimeter pack howitzers and short-barreled 105s. In the last hour of daylight they registered on the sandspit and the black, muddy east bank of the Ilu. Wildcats and Dauntless dive-bombers raked the enemy positions. From their deep foxholes the Marines checked their weapons. Some prayed. Some watched the crocodiles sliding in and out of the stream. Most, however, simply felt defiant. Their blood was up. After twelve days on this miserable island, they were about to justify their presence here. One of them yelled, “Now let the bastards come!”

They came. They were, we now know, supremely confident. Colonel Kiyono Ichiki, their leader, had already written in his diary: “21 August. Enjoyment of the fruits of victory.” After nightfall he began moving his troops through the coconut trees, toward the Ilu. It was in just such situations as this that listening posts were invaluable. In the early hours of Thursday, August 20, they reported hearing Japanese voices and “clanking noises.” They were drawn back behind our wire, and shortly before 3:00

A.M.

the Nips struck. Their sickly green flares burst overhead, followed by the chatter of Nambu light machine guns, the

bup-bup-bup

of their heavy machine guns, and the explosion of their mortar shells among the Marine foxholes. The light from the flares disclosed a frightening horde of Japs in battle dress on the far side of the sandspit. Screaming, “Banzai!” they charged. Riflemen of the First Marines picked them off while our 37-millimeter canister shells exploded on the sandspit. The enemy's first wave faltered; then a second wave came on, and then a third. Because the wire was inadequate — thousands of spools had left with Fletcher's ships — some of the attackers got through. Three of them rushed the foxhole of a corporal firing a BAR. The BAR jammed. Shouting, “Maline, you die!” one Nip jumped into the hole. The corporal grabbed his machete and cut the Nip down; then he jumped the other two Japs and hacked them, too, to death. One Marine machine gunner was killed; his rigid finger remained locked on the trigger, scything the enemy. Blinded by a grenade, Al Schmid, another machine gunner, continued to fire, directed by his dying buddy. At daybreak nearly a thousand Jap corpses lay on the sandspit. The surviving Marines, still in combat shock, stared down at them. Most of the bodies looked alike. There is little variety in the postures of violent death. When the end comes instantaneously, the rag-doll effect is common. If there are a few moments of awareness between the wounding and the dying, muscular spasms draw up the legs and arms in the fetal position, and hands are clenched like boxers' fists. Somehow cadavers always seem smaller than life. The Nips were smaller than we were anyway; their dead looked like dwarfs.

One reason the Ilu battle had been a Marine victory was that Vandegrift had the advantage of interior lines. The enemy had to move around our perimeter, through the worst of the jungle, but our men could be moved swiftly to any threatened link in our semicircular chain. Because of this, the position was ideal for Edson's Raiders. His battalion had first fought on Tulagi. Then it moved to Savo. Now, in the aftermath of the Ilu, Red Mike shrewdly guessed that the Japanese would try the Ilu approach again. He put one company on Yippie-towed Higgins boats which were then tugged to Tasimboko, twenty miles east of the Ilu, where, as Mike suspected, the Japs were regrouping. Startled, they fled. The Raiders spiked the enemy's guns, loaded tins of crab meat on the boats, dumped rice bags into the water, and disposed of Jap rations which had to be left behind by pissing on them.

Back within the perimeter, Edson reported to Vandegrift's G-3 (operations officer), bringing with him a half-gallon of captured sake and a warning. “This is no motley of Japs,” he said in his throaty voice, predicting another major attack soon. Native scouts bore him out; thousands of enemy troops were moving inland. Mike turned to an aerial photograph of the beachhead. He put his finger on the irregular coral ridge which meandered south of Henderson. He said, “This looks like a good approach.” Back with his men, he grinned his evil grin and rasped, “Too much bombing and shelling here close to the beach. We're moving to a quiet spot.” That Saturday afternoon he and his Raiders, joined by parachutists, intelligence sections, and other miscellaneous troops, started digging in on the bluff, the last physical obstacle between the southern jungle and the airfield. Thus the stage was set for the most dramatic fight in the struggle for the island. Later it would be remembered as Bloody Ridge, Edson's Ridge, or simply the Ridge. Foxholes were dug on the spurs of this long, bare-topped height whose axis lay perpendicular to the airfield's. High, spiky, golden kunai grass feathered the slopes of the rugged hogback, leading down to heavily wooded ravines and dense jungle.

It is Saturday, September 12, 1942. Some eight hundred miles to the west, MacArthur's Australians have stopped the enemy's New Guinea offensive at Ioribaiwa, within sight of Port Moresby. In Vandegrift's pagodalike headquarters Admiral Turner, visibly embarrassed, has just handed the besieged general a message from Ghormley informing him that because the enemy is massing fleets at Rabaul and Truk, and because Ghormley is short of shipping, the U.S. Navy “can no longer support the Marines on Guadalcanal.” And south of Vandegrift and Turner, a twenty-minute walk away, Red Mike is preparing for the stand which will win him the Congressional Medal of Honor and, infinitely more important, will convince Washington that the Canal can be saved after all. It is sad to note that this tormented, highly complex man, a victim of satyriasis, will one day find death, not in battle, but by locking himself in a garage and running his motor until carbon monoxide kills him. Yet nothing can tarnish his successful struggle for the Ridge. He correctly guessed that the Nips' supreme effort would come here, he marked out the Raiders' positions on the brow of the hogback, and by sheer force of will he kept them from breaking.

Because Edson had called this “a quiet spot,” and because they had seen so much combat in the past month, most of the Raiders and their hodgepodge of reinforcements were under the impression that they had been sent here to rest. That evening, when enemy warships entered the Sound, Edson's men assumed that the Japs' mission was a routine shelling of the airfield. Instead, the ships shelled the Ridge. Then twenty-six Bettys arrived overhead to drop five-hundred-pound bombs and daisy cutters on the Raiders. “Some goddam rest area!” a corporal yelled. “Some goddam rest area!” At 9:00

P.M.

Edson pulled the Marines back to the southern crest of the hogback. There were still two knolls to fall back on. If they were thrown off those they faced annihilation. He told his men: “This is it. There is only us between the airfield and the Japs. If we don't hold, we'll lose the Canal.” Within an hour battalions led by Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi moved up the east bank of the Lunga, pivoted toward the Ridge, and cut a platoon of Marines into little pockets. Japs who spoke broken English led chants of “U.S. Maline be dead tomorrow.” A Raider shouted, “Hirohito eats shit!” After a quick conference with his comrades, a Nip yelled back, “Eleanor eats shit!” Edson picked up his field telephone and told the beleaguered platoon commander to disengage. A precise voice replied: “Our situation here, Colonel Edson, is excellent. Thank you, sir.” Edson knew his men didn't talk like that. He was speaking to a Jap. He picked a corporal with a voice like a foghorn and told him to roar: “Red Mike says it's OK to pull back!” The platoon retreated to the next spur, moving closer to Henderson but keeping the Marine line intact.

Enemy flares burst overhead. Moving by their light, massed Japs with fixed bayonets swarmed up the slopes of the Ridge. “Gas attack!” they shrieked. A Raider yelled back: “I'll gas you, you cock-sucker!” Major Ken Bailey, who would also win a Congressional Medal of Honor in this action, crawled from foxhole to foxhole, distributing grenades. Raider mortars were all coughing together. All machine gunners were trained to fire in short bursts — hot barrels became warped and had to be replaced — but that night you heard no pauses between the flashes from the Brownings. The gunners cried, “Another belt, another barrel!” Palms were scorched in the barrel changing; tormented cries went up: “My fucking hand!” And during lulls you heard the sergeants bellowing:

“Raiders, rally to me! Raiders, Raiders, rally to me!”

As daybreak crayoned the eastern sky red and yellow, Edson assembled his officers for a breakfast of dehydrated potatoes, cold hash, and sodden rice. He told them: “They were testing. Just testing. They'll be back. But maybe not as many of them. Or maybe more.” He smiled his smile. He said, “I want all positions improved, all wire lines paralleled, a hot meal for the men. Today dig, wire up tight, get some sleep. We'll all need it. The Nip'll be back. I want to surprise him.” His surprise was a slight withdrawal along the hogback, improving fields of fire and tightening his rewired lines. Now Japanese assault troops debouching from the bush would have to cover a hundred yards of open grass before reaching the Marines, and as they ran up the slope they would be a naked target for grazing fire from the battalion's automatic weapons. Actually, we learned after the war, Kawaguchi hadn't been testing at all. He had expected to overwhelm the Americans that first night. Later he wrote that now, “because of the devilish jungle, the brigade was scattered all over and completely beyond control. In my whole life I have never felt so helpless.” Lacking interior lines, he couldn't match Edson's move. He had to do exactly what Red Mike wanted him to do: attack over a no-man's-land, and without his best men, who had been slain in that Saturday charge.

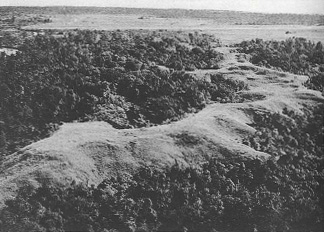

Bloody Ridge, 1978

Now it was Sunday. The oppressive tropical night enveloped the Ridge and all through the early evening there was no sign of movement in the jungle below. At 9:00

P.M.

Louie wheezed over Kukum, cut his engine, coasted over Henderson Field, and released a parachute flare. Simultaneously, over two thousand Japs charged up the slippery slopes of the Ridge. Edson's flanks were forced back until his position resembled a horseshoe. After an hour of fighting, the Japs withdrew to reform. The Raiders' mortars hadn't stopped many of the assault troops, so Edson called on heavier artillery sited near the airfield. Then, when another enemy wave appeared at midnight, the Long Toms' shells met them with blinding salvos. Edson told his FO (forward artillery observer): “Bring the fires in.” Then: “Closer.” And again: “Closer.” Terrified by the huge shell bursts, Nips tried to hide from them by jumping into Marine foxholes. Marines hurled them out. At 2:00

A.M.

the enemy charged again. Now flares showed them to be within sight of the airfield. Edson stood a few feet behind the Marine line. When stunned Raiders staggered toward him, he turned them around and shoved them back, rasping, “The only thing they've got that you haven't is guts.” At 2:30, however, both sides fell back. Edson was now on the Ridge's northernmost knoll. If that was lost, all was lost. But he sent word back to Vandegrift: “We can hold.” And the general, heartened, began to feed in his precious reserve, the Second Battalion of the Fifth Marines, a company at a time. The enemy was running out of men when, at first light, P-38s from Henderson swooped in, flying just twenty feet above the ground, strafing and firing 37-millimeter shells into the Nip reserves. Kawaguchi ordered a retreat. The Japanese dead littered the Ridge, their bodies already swelling in the heat. The Ridge was saved.

In our island war the fighting never really ended until all the Japs had been wiped out. That morning the enemy was still trying to force a passage across the mouth of the Ilu, and when five American tanks tried to descend the slopes of the Ridge, all were knocked out by Jap antiaircraft guns which had remained behind for just that purpose. During the confusing night melee, individual Nips had found their way through our lines. A jeep inching back toward Henderson and carrying five wounded Marines, one of them Red Mike's operations officer, was raked by a Nambu; there were no survivors. But the outcome of the battle was unchanged, and the losers faced a terrible prospect. Kawaguchi had to lead his men, staggering under their packs, back through the dense rainforest to the headwaters of the Matanikau, into deep, humid ravines and over towering cliffs, accompanied all the way by swarms of insects. Japs had malaria, too. They had also run out of food. And no doctors or rice awaited them. They fed on roots, leaves, and grass; they tore bark from trees; they chewed their leather rifle straps, and some, delirious, raved or stumbled into the swamps to die. “The army,” a Japanese historian sadly notes, “had been used to fighting the Chinese.”