Goodbye, Darkness (41 page)

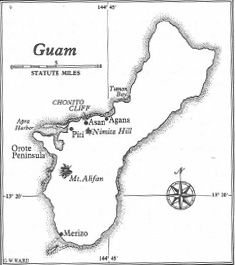

The landings were set pieces. The Third Marine Division established a beachhead beneath an eminence known as Chonito Cliff; five miles to the south, the Marine brigade puffed to the top of Mount Alifan while, on the shore below, GIs of the Seventy-seventh held the perimeter the brigade had taken at daybreak. Then Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., the Marine general commanding the force, ordered an attack across the swamp ahead. By Monday his troops had seized the base of the peninsula, isolating over three thousand Japanese Marines on the tip.

Discovering that the only road was in our hands and that they could not perforce escape, the defenders staged one of the most extraordinary performances of the Pacific war. They were bottled up in more ways than one. Orote, it developed, was the central liquor storehouse for all Japanese in the central Pacific. There was enough alcohol in its godowns to intoxicate an entire army. The sealed-off troops had no intention of letting it all fall into American hands. Instead, they planned to tie one on and stage the jolliest of banzais.

As night fell Wednesday they assembled in a mangrove swamp a few hundred feet from our lines. Not only our listening posts but our entire front line, including the Seventy-seventh's artillery forward observers (FOs) heard the gurgling of sake and synthetic Scotch, the clunk and crash of bottles, the shrieking, laughing, and singing. It sounded like New Year's Eve at the zoo. So noisy was the din that artillerymen could calculate the range of imminent targets at the edge of the swamp. At 10:30

p.m

., as heavy rain began to fall, the first wave of drunks lurched toward the American lines — stumbling, brandishing pitchforks and clubs; some with explosives strapped to their bodies; others, officers, waving flags and samurai swords. Shells from the Seventy-seventh's Long Toms landed in their midst. Arms and legs flew in all directions; momentarily there was more blood than rain falling in Marine foxholes. Screaming and milling around, these groggy warriors staggered back into the swamp. A second wave hit shortly before midnight. This time some of the souses penetrated the outposts of the Twenty-second Marines and were thrown back only after hand-to-hand struggles. At 1:30

a.m

., with every American infantry weapon hammering at them, the third wave reached our trenches before being driven back. In three hours U.S. artillerymen had fired over twenty-six thousand rounds. The crisis here was over. The next morning, Shepherd examined hundreds of the enemy bodies. He recalls: “Within the lines there were many instances when I observed Japanese and Marines lying side by side, which was mute evidence of the violence of the last assault.”

Meanwhile, five miles away, the Third Marine Division was fighting what Samuel Eliot Morison later called “a miniature Salerno” — a desperate fight to avoid annihilation. Here the enemy had no alcohol. Preparing for a counterattack, Japs patrolled our lines under cover of darkness and found a gap between two rifle regiments. The Americans had little room for maneuver. They were perched on the brink of Chonito Cliff, an almost perpendicular drop of scree and shale and small boulders, treacherous and unstable to a frightening degree, the whole dangerous slope broken only by small ledges of rock about halfway down. Engineers at the base of the cliff had rigged a wire trolley to haul up ammo and rations and to lower casualties down, which illustrates the precariousness of the American position. At 4:00

a.m

. Wednesday the Nips launched a ferocious, carefully coordinated assault: seven battalions determined to throw the Marines over the cliff. Hurtling over no-man's-land they yelled, “Wake up and die, Maline!” (One of the leathernecks shouted back: “Come on in, you bastards, and we'll see who dies!”) It was touch and go; our men were down to two clips of ammo per rifleman and six rounds per mortar. The most dangerous point was the gap. Here the Nips penetrated to the rear echelon, on the cliff's edge, before engineers, truck drivers, Seabees, members of the navy's shore party, and walking wounded — sometimes crawling wounded — threw them back with small-arms fire and showers of grenades. At that, the Japanese would probably have won if all their officers hadn't been killed. Confused, they lost their momentum and contact with one another. Pocket by pocket they were wiped out. In the morning nearly four thousand enemy bodies were counted on the bluff and its approaches.

Appropriately, the Japs then made their last stand astride the prewar rifle range of Guam's old Marine Corps barracks. Here the conflict was very different, U.S. tanks versus Japanese pillboxes. GIs of the Seventy-seventh played the key role. Friday afternoon nearby Orote Airfield fell, and on Saturday, with the enemy in full flight, an honor guard of the Twenty-second Marines presented arms still warm from fighting while the Stars and Stripes was hoisted to the top of the Marine barracks flagpole. The issue had been decided, though the fighting was far from over. Surviving Nips crept off through dense thickets of bonsai, those dwarf evergreens which, revealing the oriental gift for miniaturization, mimic great gnarled trees in every detail, down to the writhing angles of limbs twisted in their joints by the rheumatism of time. At bay in their

bokongo,

as the Chamorros called the island's caverns, the enemy shouted abuse at their tormentors and fired out at anything that moved. But they were quickly flushed, completing a clear triumph for the Americans. The cost was 7,081 U.S. casualties — half Saipan's. The friendly population had helped. So had the frog-men, a sign of the navy's growing wisdom in the ways of amphibious warfare. Had the enemy commanders continued their stop-them-at-the-waterline tactics, the Marine Corps would now have had the bloodiest of its World War II battlefields behind it. But the Japanese didn't oblige. Tokyo was beginning to learn the lesson of Biak. Though the Nipponese were losing the war, they vowed to kill as many of the foe as possible before falling themselves. Thus the war's greatest slaughters lay in the future.

Not all Japanese liquor was stashed away on Orote, as we discovered our first day ashore on Irammiya. We were digging in for the night when little Mickey McGuire's entrenching spade hit a wooden box. “Buried treasure,” he panted, unearthing it. “Bullshit,” Horse said excitedly. “That looks like schnapps!” We counted twenty-four bottles, each in its cardboard compartment. Herr von der Goltz, having advertised himself as Maine's finest epicure, was permitted to uncork the first of them and sip it. “Rice wine,” he said, smacking his lips. “Marvelous. Absolutely terrific.” This presented me, for the thousandth time, with the problem of leadership. I never tried to inspire the section by example. Never did an NCO run fewer risks than I did, except, perhaps, on Sugar Loaf Hill, and that came later. In the words of Walter Affitto, a Marine sergeant on Peleliu, “I was not very military. I tried to lead the men by being a prankster, making jokes.” Obviously, turning the box in wouldn't tickle the Raggedy Ass Marines. The only sidesplitting would come at our expense, from the rear-echelon types who would dispose of it. Since any SOP order I gave would have been ignored by the Raggedy Asses, since we were already dug in, and since I was thirsty myself, I told each man that he could drink one bottle. Straws would be drawn for the five remaining bottles. What no one had noticed was that the labels were not quite identical. We couldn't read the complicated

kanji

characters; it didn't seem to matter. Actually it mattered a great deal. Twenty-three of the bottles, bearing white labels, were wine, all right, but the label on the twenty-fourth was salmon colored. Doubtless this had been reserved for an officer or senior NCO. It contained 110-proof sake. And I drew the straw for it.

Because my taste buds had been dulled by the wine, or my throat dried by the fear that, in combat, never lay more than a millimeter from the surface of my mind, I gulped the sake down chug-a-lug, like a beer. I remember an instant numbness, as though I had been hit by a two-by-four. Then suddenly I felt transported onto the seventh astral plane, feasting upon heaven on the half shell. I recall trying to sing a campus song:

Take a neck from any old bottle

Take an arm from any old chair

…

Suddenly I was out, the first and oddest casualty of Irammiya. I lay on my back, spread out like a starfish. Night was coming swiftly; the others had their own holes to dig; there seemed to be no Japs here, so I was left in my stupor. Despite intermittent machine-gun and mortar fire throughout the night, I was quite safe. Around midnight, I later learned, the heavens opened, long shafts of rain like arrows arching down from the sky, as was customary when I arrived on a new island, but I felt nothing. One of our star shells, fired to expose any infiltrating Japs, burst overhead, illuminating me, and Colonel Krank, dug in on the safest part of the beachhead (like the Raggedy Ass Marines), saw me. He asked an NCO, “Is Slim hit?” By now everyone else in the company knew what had happened. Krank, when told, erupted with Rabelaisian laughter — nothing is as funny to a drunk as another drunk — and dismissed the adjutant's proposal for disciplinary measures, explaining that I would be punished soon enough. Since I was comatose, I felt neither embarrassed nor threatened then. The next day, however, was another story. The colonel was right. I regained consciousness when a shaft of sunlight lanced down and blinded me through my lids. After a K-ration breakfast, in which I did not join, we saddled up and moved north with full field packs on a reconnaissance in force. I wasn't fit to stand, let alone march. My heartbeat was slower than a turtle's. The right place for me was a hospital, where I could be fed intravenously while under heavy sedation. I felt as though I had been pumped full of helium and shot through a wind tunnel. It was, without doubt, the greatest hangover of my life, possibly the worst in the history of warfare. My head had become a ganglion of screeching, spastic nerves. Every muscle twitched with pain. My legs felt rubbery. My head hung dahlialike on its stalk. I thought each step would be my last. During our hourly ten-minute breaks I simply fainted, only to waken to jeers from the colonel. I needed an emetic, or, better still, a hair of the dog. Knowing of the colonel's fondness for the grape, aware that he carried a flask which would have brought me back from this walking death, I prayed he would take pity on me. When he didn't, I prayed instead that Jap bullets would riddle his liver and leave him a weeping basket case. They didn't, but after the war I learned, with great satisfaction, that one of his platoon leaders, by then a civilian, encountered him in a bar and beat the shit out of him.

As we advanced, opposition continued to be light. The next day we reached the village of Nakasoni. There was still no sign of enemy formations, so we were told we were being held there in temporary reserve. The Raggedy Asses, always adept at scrounging, bivouacked in a spacious, open-sided, pagoda-roofed house whose furnishings included phonograph records and an old Victor talking machine with a brass horn. Because I was blessed with the rapid recuperative powers of youth — and because by then I had sweated out every drop of the sake — I felt rid of the horrors. Rip and I waded across to the adjacent island of Yagachi. We had a hunch there were no Nips there, and we were right, but we had no way of making sure; it was one of the foolish risks young men run, gambles in which they gain nothing and could lose everything. When we returned to our oriental villa we brightened upon hearing dance music; Shiloh, the officer-hater, had liberated several records and cranked up the Victrola. One tune, which haunts me to this day, was Japanese. The lyrics went: “

Shina yo, yaru

. …” Two of the records were actually American: “When There's Moonlight on the Blue Pacific (I'm All Alone with Only Dreams of You),” sung by Bea Wain or some other thrush, and Louis Armstrong belting out “On the Sunny Side of the Street”:

Grab your coat and get your hat,

Leave your worry on the doorstep,

Life can be so sweet

On the sunny side of the street

Wally Moon, he of MIT, had quickly put the record player in A1 shape, and as we came up Pisser McAdam of Swarthmore was extracting a case of Jap beer from beneath a trapdoor. The sergeant who commanded these fine troops instantly appropriated two bottles and, using his Kabar knife as an opener, beat his closest rival by three gulps. Even Bubba was enchanted with Armstrong. He said he always liked to hear darkies sing.

I used to walk in the shade,

With those blues on parade

The light was beginning to fail. I made my usual footling attempt to impose discipline, reading orders on sanitation from field manuals (“Men going into battle should wash thoroughly and wear clean clothing to prevent the infection of wounds”), and they, as usual, responded with “Heil Hitler!” I shrugged. I think we were all feeling the first moment of tranquillity since the death of Lefty. We were on a lee shore and about to break up fast, but we didn't know it then; there was a kind of sheen about us: the glow of health and with and the comfort of knowing that we were among our peers. Except for Wally, the prewar physicist, and Bubba, who at the time of Pearl Harbor seemed to have been studying some kind of KKK theology, we were mostly liberal arts majors from old eastern colleges and universities. We looked like combat veterans and that, on the surface, is what we were. But we knew campuses and professors better than infantry deployments. We belonged to the last generation of what were once called gentlemen. In our grandfathers' day we would have been bound by a common knowledge of Latin and Greek. Several of us had indeed mastered the classics, but what really united us was a love of ideas, literature, and philosophy. Philosophically we had accepted the war, and we could still recite, sometimes in unison, the poets who had given us so much joy, ennobling sacrifice and bravery. In time disenchantment would leave us spiritually bankrupt, but for the present it was enough to just loll back and hear Armstrong, croaking like Aristophanes' frogs, telling us to: